Companies approach accessibility as a checklist of standards — but a client with disabilities showed me how to think beyond compliance.

During my time volunteering at Neil Squire Society, and helping Hunter, a client with disabilities, be more comfortable using a computer, I learned a lot about how to better design from three key perspectives: cognitive, physical and visual.

But those takeaways weren’t what stood out to me the most.

The most important lesson that I learned from Hunter wasn’t a set of guidelines on how to design accessible solutions; it wasn’t just about following a checklist of compliance standards.

The biggest impact from my sessions with Hunter was being challenged on my own definition of what makes a good user experience.

What is a good user experience?

In the tech industry, we build products with a focus on usability and functionality — and rightly so, because our products should first and foremost allow the user to complete a task at hand. We do that by trying our best to ensure that the solution is efficient, easy to learn, and easy to use — just some of the values that we believe are important in a good user experience.

But from my sessions with Hunter, that’s simply not enough.

Let me give you an example in the physical world to illustrate what I’m trying to say.

Imagine that you are a wheelchair user, and you’re trying to enter a room that has quite a few steps above ground level. Naturally, there are stairs, but you see an electric wheelchair ramp that needs to be unfolded for you to get into the room — a ramp that would block the entire staircase when in use. And of course, the button to activate the ramp is not within your reach. You wait until there aren’t many people around you, and then you ask the staff nearby to help you press the button to activate the ramp. Suddenly, there’s a crowd behind you, wanting to get into the room, but the ramp is still slowly unfolding. You feel many eyes on you and hear some sighs. Once the ramp is ready, you do your best to speedily get on it and then ask the staff to help you push the button to get to the top. You sense the impatience of the crowd, and as always, you feel incapable and like an inconvenience to everyone around you.

Now let’s take a look at another example.

Imagine that you are a wheelchair user, and you’re trying to enter a room that has quite a few steps above ground level — but this time, there is a ramp right beside the steps. Naturally baked right into the design of the building, given equal importance as the staircase. Not needing to wait for people to go ahead of you, you just move towards the ramp and get into the room. That’s it. You didn’t inconvenience anyone, you didn’t need to ask anyone to help you, and most importantly you didn’t cause a small scene. You were able to do it all on your own.

Which scenario would you prefer?

In both scenarios, you were ultimately able to get into the room, just like everyone else. By definition of accessibility, you had equal access to the room in both cases. But I would argue that from a user experience perspective, you didn’t actually have equal access in the first scenario.

Yes, you were able to ultimately get into the room, but the experience of it was astronomically different than everyone else. To not inconvenience others, you waited for the best moment to approach the ramp. You had to ask for help to press the button. You had to endure other people’s impatience and annoyance.

Some may argue that isn’t a big deal. It was just five minutes of your life. But imagine experiencing that type of scenario not only once a day, but a few times a day — and multiply that by weeks, months, and even years…

Accessibility shouldn’t just be about having equal access.

It should also be about the experience of how you have access, and its emotional impact on you.

Hunter’s experience with technology

Likewise, digital products shouldn’t just enable a user to complete a task. The products should make users feel confident and comfortable when they use it. During my sessions with Hunter, I observed how they completed the same task multiple times successfully — yet they kept telling me that they felt discouraged.

I realized that their discouragement stemmed from their subconscious definition of what it meant to be comfortable using technology — that they felt they had to remember the exact steps to complete a task. I also noticed that Hunter was afraid to play around with the interface in case they would ‘break’ something or lose information.

So I shifted the way I approached our sessions. I let Hunter do as much as possible on their own, only providing prompts when necessary. Instead of asking “do you remember how to do X,” I would give them a scenario and ask, “What is your gut feeling or instinct on how to do X?” I told them that no one is an expert and remembers exactly where things are in order to do a task, especially when there are changes due to software updates, and that the best thing to do is just try to see what you would do based on what you see in the interface. Moreover, I encouraged Hunter that it’s totally okay to try things out as there are ways to revert back to previous changes.

Hunter’s sentiments reminded me that we have all, at one point or another, had similar experiences — and that perhaps our feelings of discouragement faded as our confidence in using the software program increased. Some of us may still be feeling unease and discomfort every time we use technology. Needless to say, these emotions aren’t experienced only by people with disabilities, but by all of us.

Rethinking my understanding of UX and inclusivity

I was able to encourage Hunter and enable them to feel a bit more confident using technology through this context of teaching. However, that got me thinking — is there a way to encourage users to feel comfortable using our technology through their interactions with the product itself?

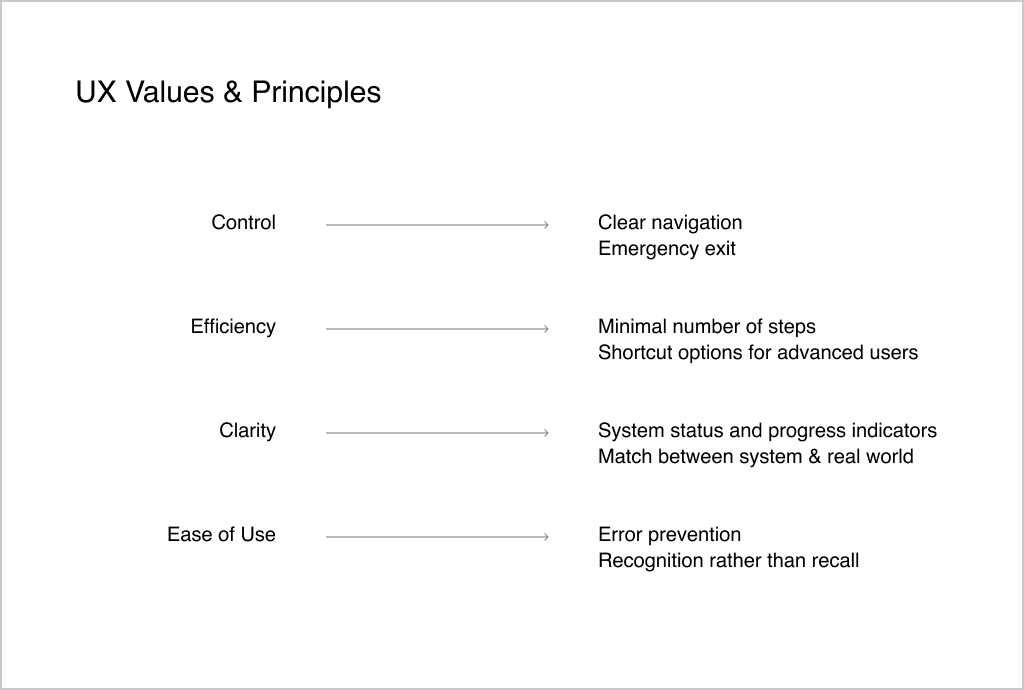

We design the user experiences of products based on the fundamentals of what makes a good user experience. There may not be a single, universal set of UX principles that exists, but there are agreed upon principles based on different schools of thought as demonstrated in Nielsen Norman Group’s 10 Usability Heuristics and the UX Pyramid framework. For example, clear navigation, minimal amount of steps, error prevention, and status indicators are a few of the shared foundational principles, and they make sense in the context of creating good user experiences that allow a user to complete a task.

But what if we placed equal emphasis on the journey to complete the task, considering its emotional impact on the user, rather than just the act of completing the task itself? What if we focused on building a wheelchair ramp that allowed wheelchair users to feel independent, instead of just building a wheelchair ramp?

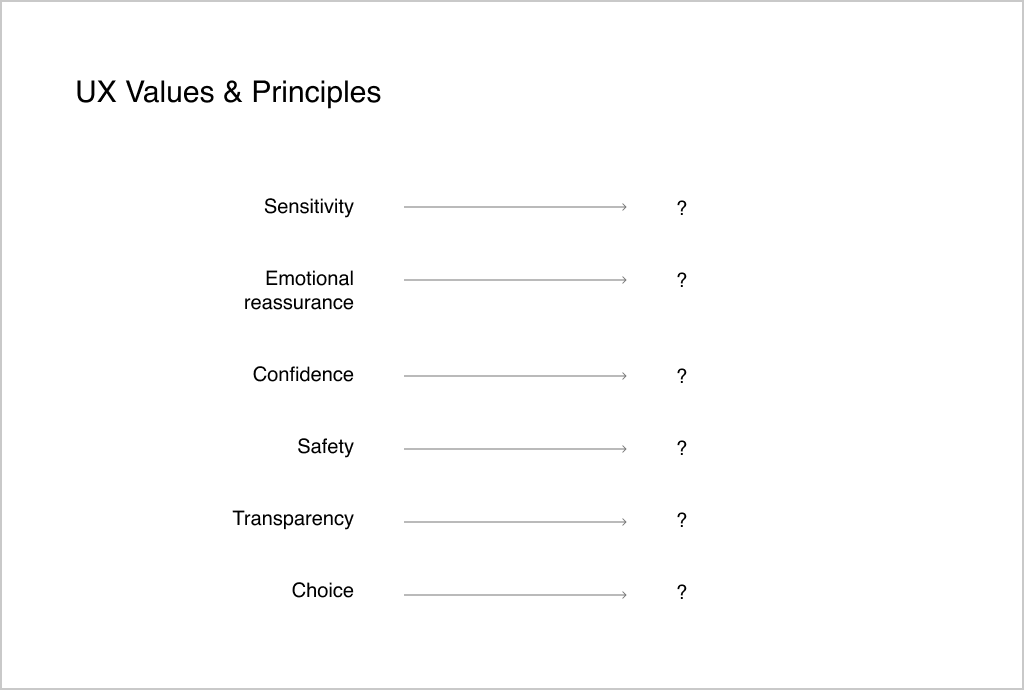

If we take a step back, the UX principles I listed above derive from values such as control, efficiency, clarity, and ease of use. Yet my experience with Hunter challenged my understanding of these UX values and principles. Have we ever thought about other values we should focus on, or whether those are even the correct values to focus on? What about values that impact the user’s emotional well-being?

We design products with efficiency in mind, but what about sensitivity, emotional reassurance, and confidence? What about safety, transparency and choice? These values may conflict with what we consider to be the foundational basics of UX, but I believe these values are just as important, if not more. What is the point of enabling a user to be able to complete and submit a form online, if the process of completing that form makes the user feel incompetent and uncomfortable? What is the point of getting into the room, if the experience of the wheelchair ramp to get into the room caused you to feel inadequate?

And why are these values not foundational to UX? Why is inclusivity seen as a “lens” to be applied in the UX framework, and not inherently integral to the essence of UX?

So many questions to think about.

What’s Next?

People who are confident using technology are comfortable with exploring an interface, and handling the uncertainty of not being able to do an action right away. As professionals in the tech field, we are probably at this end of the spectrum even more so. As a result, we can easily forget what it’s like for those who don’t consider themselves to be tech-savvy.

Those who aren’t comfortable with tech can feel constantly uneasy when they use a program, and may even attribute it to their level of intelligence. This is especially the case for those who have a disability, who already deal with a lot of challenges in society outside of technology.

We need to not only be empathetic, but also sensitive to other’s inner emotions and needs. We need to create products in a way that doesn’t just let them functionally complete a task, but also creates a positive emotional impact.

I understand that there are many challenges we face in our teams today as we pursue accessibility and inclusivity — tight timelines, lack of expertise, and fear of doing the wrong thing. Perhaps the biggest challenge of all to overcome is the fear of diving into this new world, where we may feel uneasy and uncertain of how to navigate it, or that an all-or-nothing attitude is required of us.

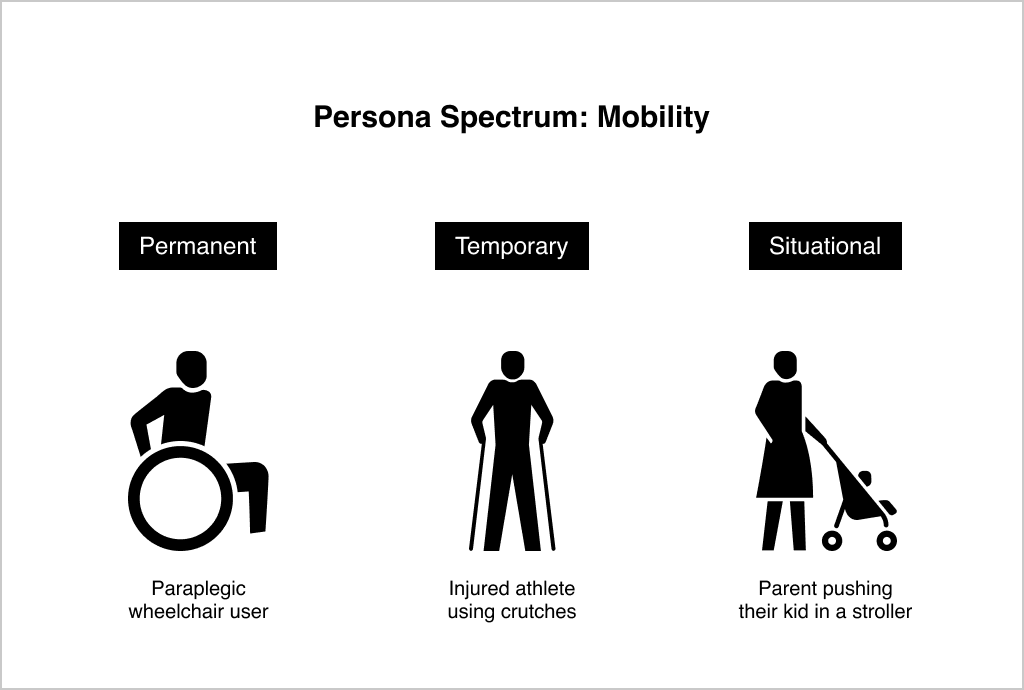

But that’s exactly where we need to stop and reframe our thinking — because accessibility isn’t another world. Many of the frustrations experienced by those with disabilities are not exclusive to them, though it may be amplified for them. Solutions that may only seem to help those with disabilities actually benefit all of us in different situations — wheelchair ramps can be used by a parent pushing their toddler in a stroller, an injured athlete straining to walk with crutches, or a tired traveller lugging their wheeled suitcase. Accessibility means we take into account the wide range of functional abilities of those who identify as non-disabled and disabled in permanent, temporary and situational contexts.

I would encourage you to start by looking into inclusive design tools like the persona spectrum, which I learned about from Kat Holmes’ book Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design (I highly recommend this book!). Another approach is to choose one value of emotional well-being to focus on, or pick one practical tip you can try in a project with your team. Just commit to taking one small step, one tangible thing that seems doable, and see what happens.

To end off, I’ll share something that one of the program coordinators from Neil Squire Society said that really struck home for me:

“Something can be designed to be accessible, but it might not be user-friendly.”

Designing for accessibility beyond compliance was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.