Tools to mitigate commitment bias and overconfidence

Last week, we wrote about how ‘conviction’ is a very human attribute responsible for our powerful, yet irrational ability to almost will positive outcomes into existence; presumably against all odds.

Today we’ll cover the dark side of conviction and overconfidence — and unfortunately, the more common tendency to overcommit and hold on to our losses.

Confidence and resilience are hailed in scenarios where it all worked out, but it’s rare we recognize the many times it doesn’t work out — due to outcome bias, survivorship bias, and hindsight bias.

When systematic overconfidence might be good…

90%+ of startups fail in the first three years. 20% of all new businesses fail within the first year. Even within large organizations, 95% of new product releases or ‘innovations’ fail.

Should we stop starting new companies or chasing innovative ideas? No.

When systematic overconfidence is bad…

A study of 258 large transportation projects built between 1927 and 1998 in 20 countries found that 90% of projects were more expensive than expected.

On the other hand, 86% of construction projects exceed their initial estimate and cost an average of 28% more than anticipated.

Should we do something to reduce the overconfidence that drives wildly inaccurate estimates and escalation of commitment? Yes!

We are systemically overconfident. There are plenty of studies that show consistent overconfidence in our abilities, but the most popular demonstration of the better-than-average effect is when we’re asked about our driving skills.

“Despite the fact that more than 90% of crashes involve human error, three-quarters (73 percent) of US drivers consider themselves better-than-average drivers. Men, in particular, are confident in their driving skills with 8 in 10 considering their driving skills better than average.”

The research behind optimism bias, illusory superiority, and the dunning-kruger effect shows that we’re often overconfident in both our abilities and the probabilities of positive outcomes — and we’re typically blind to it.

We’ve explored when conviction and ‘warranted’ overconfidence can be a good thing (particularly in radically uncertain environments), but can we effectively identify when it’s a negative factor and guard against its effects?

When do we need to mitigate overconfidence?

In the previous examples above, we had two very different scenarios.

Most founders believe their startup will succeed (against all odds) and if we believe there’s positive intent, most contractors don’t overestimate projects on purpose.

Can we differentiate between scenarios when confidence and conviction might be good vs bad?

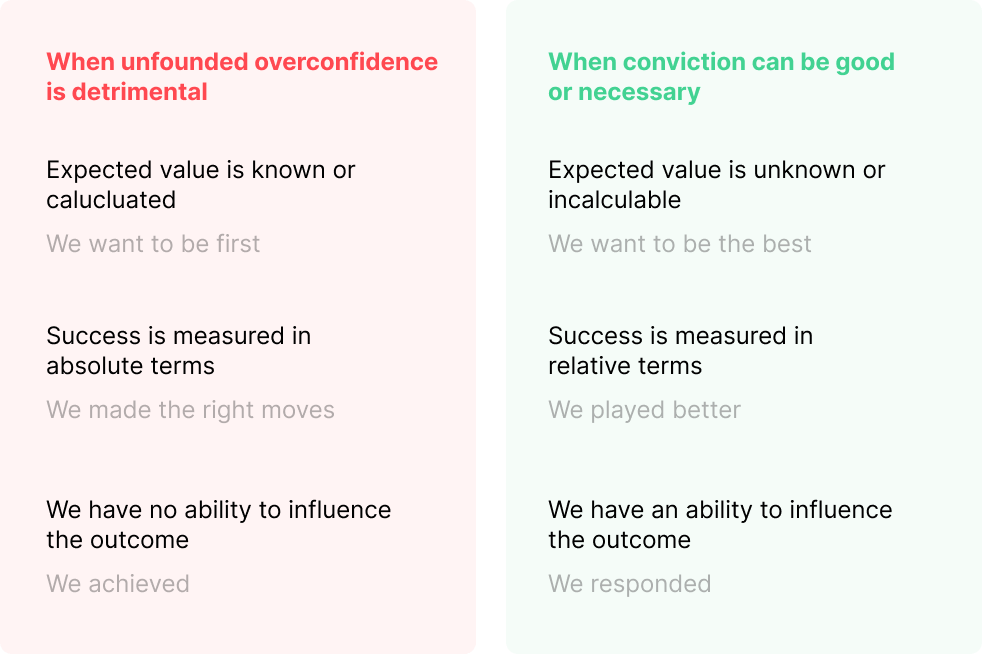

Based on what we’ve gathered from a biases and heuristics perspective (all overconfidence is bad), from the naturalistic decision making perspective (it’s warranted in high-validity environments), and from the more nascent studies in environments of radical uncertainty (how would we ever do anything innovative without some overconfidence?!), we might end up with a mental model like this:

But in environments where conviction and overconfidence play a meaningful role in success vs failure, success is still the exception, not the rule — often due to factors not in our control (e.g. luck), but for the factors within our control, we lack the ability to adjust and respond to new information.

Even in scenarios where overconfidence is warranted (in this case, meaning there is a compelling hypothesis making up for a certainty gap), there’s a big risk that we’re on the slippery slope toward commitment bias.

Tools to combat overconfidence

The cognitive biases that create the lethal combination of overconfidence and escalation of commitment are self-reinforcing.

We tend to diverge too quickly (Anchoring bias, Availability Bias), immediately entrench ourselves (Confirmation Bias, Belief Bias), and hold on for too long (Commitment Bias, Sunk Cost Fallacy).

Shane Parish, founder of Farnam Street and a long-time researcher of decision making science describes conviction as powerful, but rare — as if there’s a sign that says “Break glass in case of radical uncertainty”

Great decision makers aren’t great ‘choosers’, they’re architects of their own decision making system. They create environments where they retain optionality (choosing from multiple good options), make hard decisions easy (through models like principles and ‘even over’ statements), constantly update their assumptions when new information arises, rarely leaning on conviction — but when they do have conviction, they’re all in.

Shane Parish, Decision by Design (Paraphrased)

Annie Duke also covers this topic extensively in her book, Quit: The Power of Knowing When to Walk Away — exploring why we tend to stick to things far longer than we should. She challenges the intoxicating nature of ‘grit’ and ‘sticking with it’ and argues that quitting is a valuable skill when navigating uncertainty.

In many cases, we tend to focus more on signals that something is working rather than not working — even though the latter may be, more often than not, more meaningful.

“At the moment that quitting becomes the objectively best choice, in practice things generally won’t look particularly grim, even though the present does contain clues that can help you figure out how the future might unfold. The problem is, perhaps because of our aversion to quitting, we tend to rationalize away the clues contained in the present that would allow us to see how bad things really are.”

– Annie Duke, Quit: The Power of Knowing When to Walk Away

In short:

- Conviction can be a powerful tool but should be used sparingly

- Overconfidence and commitment bias are like a riptide — often taking us too deep into trouble before we know it

- We need to utilize tools and techniques that help us spot when the efficacy of a decision has altered with new information

Below are a few tools highlighted by Annie Duke, among others, to help mitigate the effects of commitment bias and overconfidence:

- Kill criteria and ‘tripwires’: Tools for setting predefined thresholds that trigger the reevaluation of decisions — Annie Duke, Chip & Dan Heath

- Premortems: Taking a future perspective and identifying potential negative outcomes to proactively mitigate risk — Gary Klein

- Monkeys and pedestals: A framework for identifying and focusing on complexity over building false confidence with trivial tasks (bikeshedding) — Astro Teller

This post was originally featured on the Uncertainty Project

Our dangerous tendency to hold on to losing bets was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.