Some of us are both designers and parents. Some of us may have designers as parents. Some of us may even be designers creating products for children. Nevertheless, all of us were once children. Being a child may be a distant memory, to an extent we forget what it is like to be a kid. If we could recall, there was a sense of wonder where we will discover what lies behind what we see. There was a sense of curiosity when we probe and find a reason for our little minds. There was a sense of tinkering when we take a crayon to sketch out our ideas. And there was a sense of satisfaction every time we create something with our hands. These may be the memories of a 5 year old in kindergarten, yet they strangely look like what we see as a mindset of any design professional.

There was once a tale told by Daniel Pink and Tom Kelley about a man named Gordon Mackenzie, the former creative maestro from Hallmark cards. Being a patron of education, he would visit schools to share about his occupation as an artist. As he glanced around the classroom, he will take the chance to engage the students whenever he saw an artwork on the wall.

“How many artists are there in the classroom?”

was the question Mackenzie would ask, followed by a request for the class to raise their hands. In kindergarten and first grade, he would see every hand raised up. In second grade, there were some hands not raised, and a little reluctance. In third grade, only a handful raised their hands. By the time he reached sixth grade, there were only cautious glances to see if anyone raised their hands. It was a recurring pattern during his time. I would dare say the same for any other creative fields, including design.

https://medium.com/media/41e2e4100a8c804b6daab40826d0a6ef/href

My journey in becoming a designer

I recalled my time as a kid growing up in a cosmopolitan Asian setting known as Singapore. Dad and Mum had jobs that dealt with numbers. Hence, they expected me to go down the same logical path. Needless to say, whilst I appease them with the numbers via the grades, I was quietly going down the other path (If this is confusing to you, the latest Pixar movie, turning red, captures this contradiction about Asian families very well).

Occasionally, I would doodle on the pages of my school textbooks, only to be reprimanded by my teachers. Recess was spent more on drawing comic strips and designing game scenarios in a Wimmelbilder style, rather than playing soccer. At one point, I started learning how to draw human figures but was ridiculed by my classmates, close to a fist fight. When the conscious decision to pursue a design education came at pre-tertiary, my parents were confused and had a hard time understanding my choice. Yes, the backdrop of my design life was evidently filled with doubt and a sense of misfit, similar to the kids in sixth grade. In my heart, I was the only soul raising my hand at sixth grade.

Going to a design school at university changed everything. Suddenly, I had peers who were more visually inclined, but were also vulnerable having emerged from similar constructs of education. We were raw with creative potential, and we were speaking a common language of design. Doors were subsequently opened when I was exposed to other design disciplines in different settings. In student exchange, I discovered service design. In postgraduate, I discovered computational (UX/UI) design. From these experiences, I would consider myself a very lucky kid, because I had stumbled into a narrow path that led me to design. As I think about the lives of children with different backgrounds, how many of them will have the same chances as myself? Each hurdle is presented to a kid: ethnicity, filial piety, income, peer influence… the list goes on. These factors can diminish the chances of becoming a designer. Picture young children at a street market in a South East Asian country, peddling to make an income for their family. Would they consider design if they had access to better education?

Where is design education today?

To feel belonged at university feels like a long journey for a 5-year-old. Thankfully, there are emerging initiatives in the 21st century. In Singapore, a Design Education Advisory Committee is formed in 2020 to shape the quality of design education in universities and polytechnics at the national level. Singaporean students are also being exposed to bottom-up initiatives through school programmes and workshops led by social enterprises, such as Design for Change Singapore, leading to anecdotal examples of design thinking seen across various primary and secondary schools. Increasingly, the movement has become global, with more countries adopting design education seen by the network of design institutions, such as Design for Change Global and Design Factory Global Network.

Yet, it takes a village to raise a child. Whilst educational institutions are very important, more can be done beyond the school gates, especially in the homes of impoverished states. Whilst modern societies like Singapore are advancing in these areas, other countries are either playing catch up, or have not yet started. Without exposure and accessibility to design education, children continue to live their lives in prescribed paths. With exposure and support, you might get yourself an architect like Francis Kéré, who won the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2022. He is now designing buildings with the communities who supported him, which in turn inspires the next generation of designers in Africa.

3 ways to have more design in a child’s life

Can the design path be wider for more 5 years olds to tread on? I personally feel that the answer is a definite yes, and we as designers have the ability to make it happen. The onus is upon us to now make the change for a new generation of designers. Here are 3 ways we can do that for them.

- Go beyond the design groups and befriend the pre-designers. As much as there are wonderful mentoring platforms out there, which foster engagements between designers, more effort can also be extended to pre-designers by partnering social enterprises providing enrichment and services to children. You might ask: who are the pre-designers? These are the children who have the creative potential inside them, and need an external spark to ignite a creative fire, with the encouragement to glow in it. Consider another award-winning creative master, Jon Batiste. In a recent interview, he credited his music proliferation to his family, peers, mentors and community during his growing up years. Remember the village, and we are the villagers.

- Stop over-emphasising STEM disciplines. Even with the weak attempt to add “A” for the everything arts, forming the acronym STEAM, there is neither any firm association to hot water vapour, nor is there a means to bind the disciplines together. Ironically, STEAM still feels more of a forced relationship (the phrase Hot air means insincere and having no practical result) than a cross disciplinary approach. What if we include the Renaissance in the mix, anagrammatizing it to form the acronym MASTER? With polymaths likes Nicolaus Copernicus, Da Vinci and Christine de Pizan, Renaissance helps to create an aspiring archetype, and acts as the “glue” of multiple disciplines. It is a timeless concept that continues to inspire new masters, even in the 21st century. Think Melanie Perkins, who started out as a private tutor teaching students graphic design before turning the content creation business on its head with Canva. Consider her background in communications, psychology, commerce, graphic design and sports (For more on the New Renaissance, check out the book, Age of Discovery by Ian Goldin, Chris Kutarna)

- Start bringing our skills closer to 5-year-olds, through the medium they are most familiar with: books. Out of the many design examples, it was Shinsuke Yoshitake’s solo picture book, Ringo kamo shirenai (tr. It Might Be an Apple) that struck a chord in me. The story is written as a children book based on a young child exploring ideas of design. What amazes me is Yoshitake’s humour and imagination in bringing magic to a banal object. How might we introduce such ideas to our little extreme users (ie. kids)? It may require us to go out of our comfort zones, by designing beyond our range of the typical user groups. On that front, writing has prompted me to revive one side project: writing a children’s book about being a designer. Perhaps through this project, I will have a chance to rediscover what it means to be a desiger and a father.

I am currently a father of 2 young children, making me the designer/parent archetype. As a designer, I am inspired to use my knowledge and expertise to bring design education closer to younger kids. But as a parent, I want the best for my kids.

https://medium.com/media/d43ab3bcaf1fafdd1054c4bcb69428a0/href

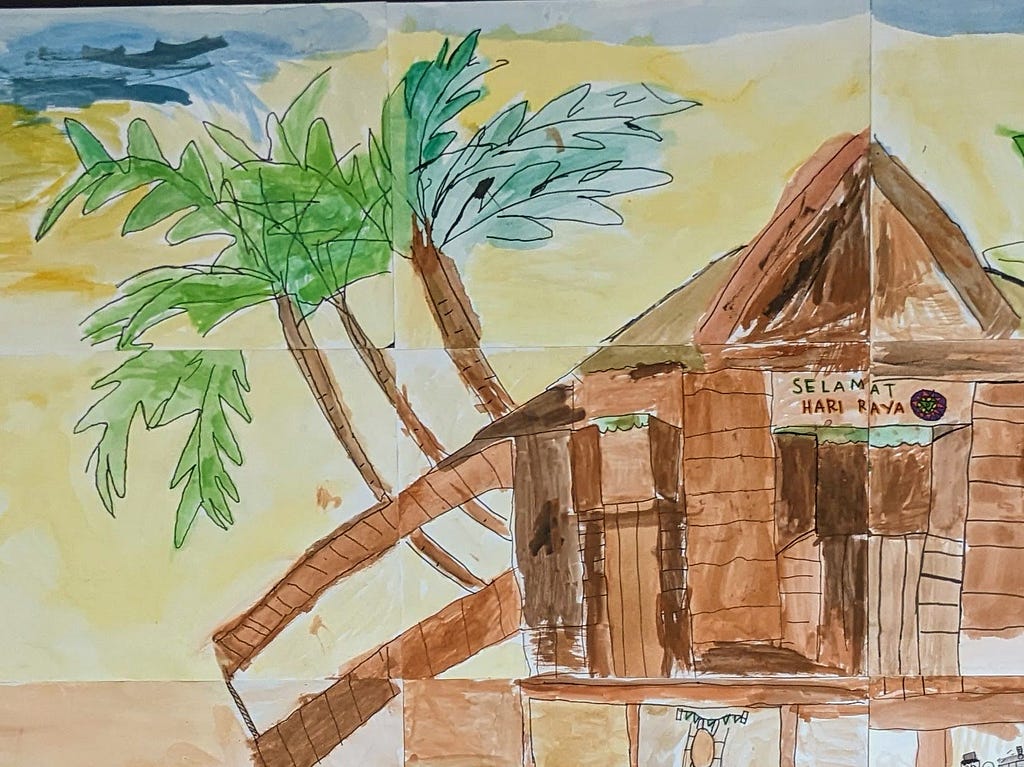

I leave with a final note: I later realized that Mum was actually more of the artist in the family. In the later part of her life, she is no longer working with numbers. Instead, she has embarked on creative art projects and has been the person who reintroduced painting to me as an adult. Turns out that her creative path wasn’t as clear when she was a 5-year-old in the 1960s, but it was rediscovered when she was in her sixties. Whilst I wished that she could have discovered her creative potential earlier in life for her 5-year-old son, I’m grateful that she(and my Dad)took the leap of faith and released me to pursue my design education with freedom. Likewise, I hoped for the same creative freedom for my 5-year-old children and the future generations of designers.

It takes a village to raise 5-year-old designers was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.