A snapshot of the emerging framework that expands human-centred design to consider all peoples, all sentients, and all planet.

Life centred design is an emerging design approach that expands human centred design to also include consideration of sustainable, environmental, and social implications. It connects micro-level design (UX, product engineering, etc.) to global goals by increasing the stakeholders from just ‘user and business’ to ‘user, non-user, local and global communities, ecosystems and planetary boundaries’.

Some of its supporting practices have been practised for decades but are still ‘emerging’ into mainstream design, while others are new and just finding their legs—circular design, systems thinking, and biomimicry, to name a few.

As life centred design is still emerging, however, awareness of it is low and approaches vary and go by different names—planet centred design, planet centric design, conscious design, 21st-century design, environmental design, circular design, DesignX, respectful design, and humanity-driven design, among other terms. But all eschew focusing only on commercial and modernizing goals in favour of more collaborative, inclusive, holistic and sustainable approaches.

Meanwhile, thousands of micro-level designers are continually creating many new physical and digital experiences every day, and thousands of new UX designers are pumped out of institutions every year without a deep awareness of the potentially limiting and destructive impact of their human centred design training. Life centred design needs these minds and their perspectives, for it thrives on plurality.

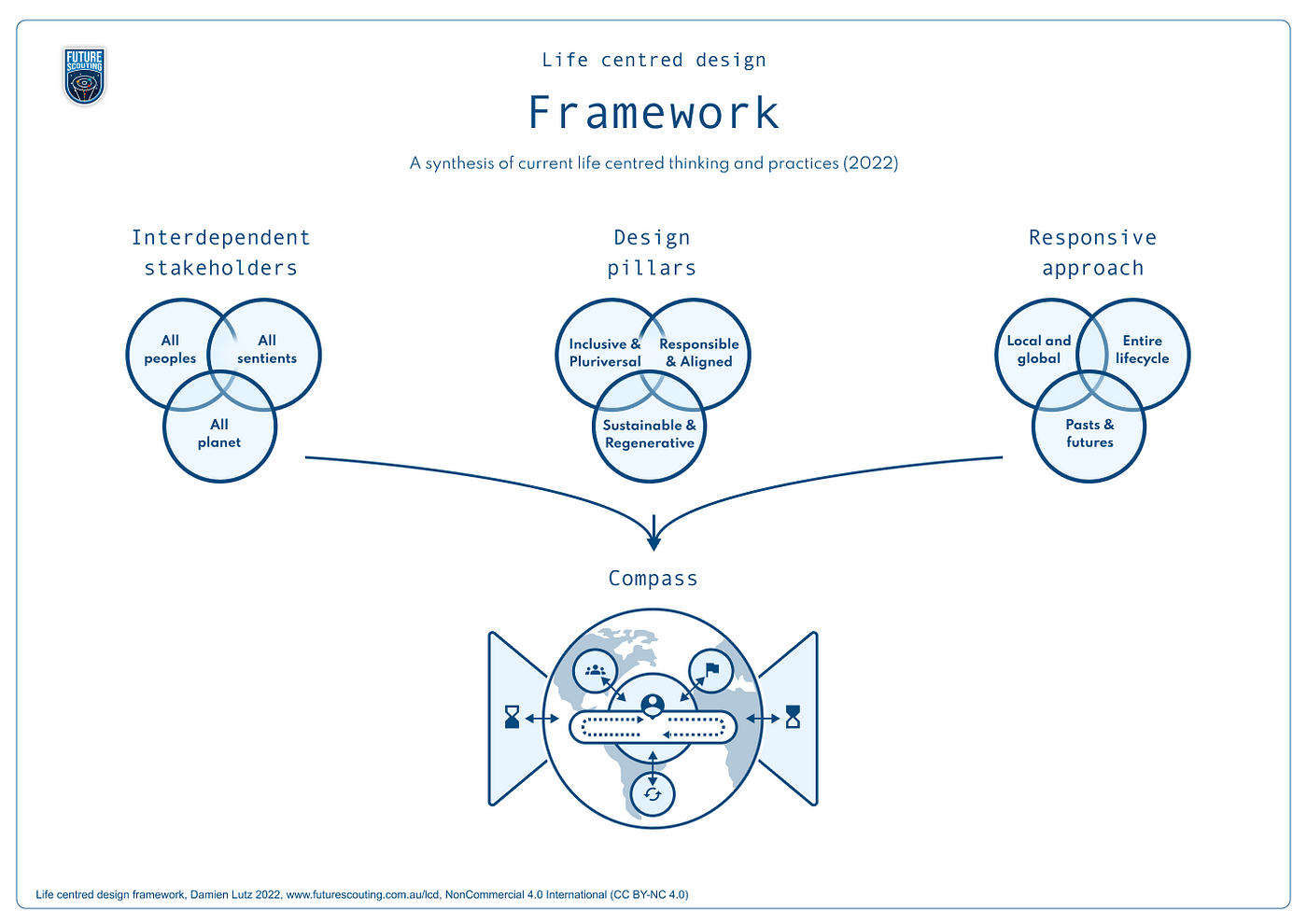

To make life centred design more discoverable, I reviewed over 20 life centred design approaches to create one hypothetical ‘future snapshot’ that merged all approaches, defining the 3 Interdependent stakeholders, 3 Design Pillars (including supporting design practices), and the Responsive Approach as a guide for both physical and digital product designers, service designers, and business decision-makers to start learning and contributing to life centred design’s emergence.

Some of the approaches reviewed:

- Disruptive Design—a multi-disciplinary approach combining design thinking, sociology, environmental sciences, cognitive sciences and systems thinking which they also teach via The UnSchool of Disruptive Design

- Circular design—as per The Circular Design Guide, a circular economy accelerator created by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and global design company IDEO

- Planet Centric Design—by Vincent, a software development and digital transformation company in Finland, which focuses on reducing the environmental impact of digital services

While life centred design strategies are mostly relevant to the design of physical products, and to the design of a business, the life centred lens opens our minds to the hybrid physical/digital nature of today’s creations and to the impacts of our digital-first experiences on the physical world. Therefore, life centred design is for both physical and digital product designers, service designers, and business decision-makers.

Life centred design’s wider stakeholder view connects product and experience designers working at the micro-level with global environmental and social goals at the macro-level, such as those of the Doughnut Economy and UN Sustainability Goals.

The Doughnut Economy is an alternative economic model to today’s dominant take, make, and throw away mentality. Introduced with the book “Doughnut Economics” by acclaimed economist Kate Raworth in 2017, the Doughnut represents a “safe operating zone” between an outer ring of planetary boundaries that we should not overreach, and an inner ring of safe, just, meaningful, and thriving existence that all peoples must remain above. The space in between these two thresholds is the Doughnut, the target area where all activities should be focused in terms of outcomes and impacts.

The United Nations Sustainability Development Goals (SDGs) are 17 interconnected global goals aiming to ‘end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that by 2030 all people enjoy peace and prosperity’.

Life centred design also reconfigures today’s idea of a product’s lifespan from being purchase-use-discard to including the extraction of raw materials from the earth, the processing into parts and transportation and selling, to their first use. Discard leads into circular loops of reuse, repair, refurbishment, and recycling, with all waste converted into a resource for some other part of the system.

This extended and looping product lifecycle is framed within the circular economy which aims to keep raw materials in use for as long as possible to extend their value, and to reduce the need and energy to extract any more.

Viewing the product in its true lifecycle also helps view the product as a system of actors and relationships that spans years more than human centred design has us consider and impacts multiple human and environmental systems over that longer lifespan.

While global circularity is only at about 8%, support for the circular economy is increasing:

- Netherlands, France, Italy, Spain, and Germany lead the way with varying initiatives including waste reduction and business investment

- Swedish fashion house Fillipa K have translated their circular process into specific life-centred goals, broken down into achievable short-term and ideal long-term goals, including aiming for full traceability, improving garment longevity, and increasing the resell, remake, and recycle of garments and cutting waste, and committing to fair, safe, and non-exploited work conditions

- Apple pledged to create all of its products from recycled materials. By 2020, they have made the iPhone 11 product line circular and created the device entirely from components of older Apple products.

- Inspired by the Global Fashion Agenda, Nike produced Circularity: Guiding the Future of Design, a guide for the sports fashion industry to create long-lasting and circular products, based on their own endeavours such as refurbishing used shoes to resell and incorporating material offcuts into their new products.

The blooming of life centred design today acts like a reset of current product and digital design to include all of our learnings to date — from human-computer interaction design, human-centred design, design thinking and user experience design, and service design — and incorporates past and future views, to form a more holistic approach to today’s planetary emergency and human disconnection.

But the essence of today’s life centred thinking is older than readily available western histories record. First Nation peoples have practised sustainability and systems thinking for thousands of years. This disconnect between today’s ‘innovative’ thinking and traditional wisdom from the past(s) is just one persistent problem with modern design that life centred design aims to fix and heal.

Life-centred design is a regenerative, responsive, and pluri-clusive framework synching responsible businesses with global goals to design products and services that minimise harm, re-nourish the planet, and foster just and diverse ways of being.

It’s important to note that life centred design is not a silver bullet, and there are challenges to its potential.

As an emerging framework, varying approaches are practised by many innovative companies and individuals. They all have their own unique perspectives and values, some align with the SDGs while others don’t, and some focus on sustainability without as much focus on inclusivity as others. An ideal future state of life centred design could be one that merges all current variations.

This is not a proposed final framework — something like that should be a product of co-creation, and it is already being worked on from an educational perspective by The Future of Design Education Initiative.

The purpose of this snapshot is to:

- Improving the discovery of life centred design

- Contributing to its emergence by generating discussion and experimentation

- Creating a steppingstone to further education about life centred design and the supporting practices

- Accelerating the transition to more regenerative and just local and global relationships between all peoples, all sentients, and all planet

Life centred design’s stakeholders can be identified as 3 larger groups, with human centred design’s target-user and business stakeholders included and remaining at the centre, but no longer considered alone:

- All peoples — Target users, Non-users (Individuals, communities, and employees of organisations working within the product lifecycle); Invisible humans (individuals and communities not involved in the lifecycle but who are impacted by it); All human knowledge and ways of existing; All sentients

- All sentients — All non-human lifeforms on land, water, or air that have been shown to register pain, compassion, memory, and some cognitive function

- All planet — All planetary ecosystems and their lifeforms (plants, etc.), resources (water, air, etc.), and the planetary boundaries

1. Sustainable and Regenerative

Sustainability is often accepted as perpetuating today’s business models in a way that ensures enough resources remain for future generations to get by. Regenerative design focuses on giving back much more than is taken — generating positive impacts for the environmental and human systems that our activities support or draw from — so that humans co-evolve harmoniously with nature.

A regenerative business ensures the social, economic, and resource sustainability of the product lifecycle by zooming out to share prosperity with the ecosystem of the product/service lifecycle and regenerate the sources of energy it takes from, nurturing resilience for all.

2. Inclusive and Pluriversal

Inclusivity focuses on the diversity of gender and sexual identity, culture, race, colour, age, etc., with a particular focus on the diversity of abilities. While these considerations are extremely important, pluriversal thinking takes design even deeper into human diversity by championing diverse ways of existing beyond the Western, capitalistic, hetero, patriarchal, and hierarchical perspective, with its mantra of constant economic growth.

Born from the peoples marginalised by the globalisation of Western globalisation, pluriversal design reminds us of the power and historical damage of design so that we may deconstruct our design approach to design for an inclusive and diverse ‘world of many centres.’

3. Responsible and Aligned

Responsible businesses and designers are transparent, accountable, and science-based. They guide users and partners by example toward responsible stewardship of the resources they use, and they zoom out to align with global goals and ally with the supply chain to nurture circular, regenerative, and just innovations.

The three Design Pillars can be achieved by employing an attuned and adaptive approach that responds to all needs by taking a wider lens across space and time for consideration of full impact and opportunity:

- Local and global—Foster autonomous and interdependent futures by responding process to people; Zoom in and out between systems thinking and locally attuned perspectives, between traditional and modern knowledge, and between human and nature-based strategies, to connect micro-level activities to global goals

- Design for entire lifecycle—Take responsibility for the true lifecycle of the product/service — from material extraction and manufacturing to shipping, selling, use, reuse, repair, remake, recycle — and its impacts on all peoples, all sentients, and all planet

- Consider Pasts and Futures—Honour alternate pasts and possible futures to protect all past wisdoms and future stakeholders

Design for life centred design’s interconnected stakeholders by using the responsive approach and aiming to achieve the three design pillars.

As you can see, there’s a lot to life centred design.

The 21st-century designer will become more of a facilitator of creation, by merging their academic skills and knowledge with the local, traditional, and pluriversal aspects of the design challenge.

Don Norman notes that today’s designers already have the skills needed to tackle global issues:

- People-centred

- Identify and solve the right problem

- View everything as systems

- Make impactful iterations

Life centred design expands and recontextualises these skills to enable designers to work from micro to macro level projects.

With the current and future state of the world growing more VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous), people and the environment could use all the life centred design thinking they can get.

I’ll share more of my research into life centred design soon — subscribe to be notified, and check out The Life Centred Design Guide coming soon.