I recently published a scientific paper on the Interactive Behavior Change Model (IBCM).

The IBCM is a behavioral science system I developed during my doctorate studies. It is comprehensive, with an intuitive, theory-based structure that is easy to learn and grounded in the science of building digital products.

But best of all, it’s an excellent choice for AI-infused behavioral product design.

Publication URL: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/373530823_Correction_to_Interactive_Behavior_Change_Model_IBCM_80_Theory_and_Ontology

Rather than describing the IBCM, I’m going to help you understand it from the perspective of why I needed to develop it. Sometimes, the best way to understand something is through the author’s firsthand account.

I’ll also explain how the world’s most comprehensive and theoretically grounded behavioral science system got locked up for a decade.

But be warned, I’ll be stern about malpractice in our field. Some may find my perspective harsh. But this is tough love. And it will help some of you improve your standards.

By the end, I hope you will feel more street-smart and better equipped to manage the truth, lies, and uncertainty in our field.

Seeking the psychology of technology

In 2006, I did something that might sound insane. I quit my dream in the United Nations Climate Change Secretariat to gamble on what many considered a ridiculous Ph.D. topic.

At the time, I believed that if I could distill the psychology of online influence, I could use it in scalable social change campaigns to nudge humanity toward a sustainable future.

By today’s standards, this is nothing special. But in 2006, most people believed that psychology didn’t work online. They also thought that you couldn’t have meaningful relationships online either. Using it to nudge an entire planet was crazy.

Fearing a life of regret, I resigned from the United Nations and joined Prof. Thelwall (http://www.scit.wlv.ac.uk/~cm1993/mycv.html) to discover the psychology of technology.

Source credibility and trust

When starting a PhD, many believe they are on the brink of discovering Nobel Peace Prize-winning insights that will transform science. That’s not how it works. Typically, your advisors tell you to focus on a tiny original contribution, meet the criteria, get your doctorate, and get out before you’re bankrupt.

They don’t yell, save humanity. They yell, save yourself.

Early on, I pinpointed source credibility and trust as core factors in online behavior change. When your audience trusts you, it’s easier to nudge them. It is not because trust drives behavior; rather, distrust stops it.

Distrust causes people to reframe your slick psychology as a manipulative threat.

So you can think of distrust as the ultimate deal breaker. It’s triggered in milliseconds by subtle cues that nobody fully understands. I won’t get into the science here, but there’s good evidence that trust is the single most important moderator of influence.

Keen to share my findings, I published my first study at the Persuasive Technology conference. Luck was on my side when the scientific committee recognized my research as a top submission and invited me to publish a longer peer-reviewed journal paper.

What happened next was amazing. Within a year, I was published and had done so much work that I met the minimum criteria to earn my doctorate. And this gave me an unexpected gift. As a rebel, there’s nothing more enjoyable, than doing what you’re not supposed to do.

But with my doctorate largely secured, I decided to tackle the ambitious project everyone warned against. Here’s what I cooked up.

At the time, nobody could tell you which behavior change principles were the most/least effective, how they combined, and which were fake. For instance, do you think that soiclal normative pressure is generally stronger or weaker than a placebo? What’s stronger, a threat or an incentive, and how does trust impact this?

Nobody knew how all the principles combined, or how they compared.

So I developed a method for measuring every single behavior change principle in technology. With this, I could pinpoint what worked and finally collect evidence to silence those ridiculous pop psychology authors who shill pseudoscience for a living.

To accomplish this, I needed two things.

First, I needed a magical shopping list of every behavior change principle that was proven to influence people in interactive media.

Second, I needed to perform a statistical meta-analysis to measure the impact of each principle and its context.

Both were incredibly difficult. Here’s how I pulled it off.

Judging behavior change taxonomies

My first challenge was to find the magical list of all behavior change principles that work in online media. With this list, I could audit digital products and reverse engineer their psychological design patterns.

I started by collecting every behavior change system I could find. I wrote to every relevant community, searched all over, and went everywhere I could.

There are many taxonomies, each with its area of specialization, scientific assumptions, philosophy, and more.

When you spend years comparing behavior change systems, you inevitably become quite the snob. So I may sound very harsh at times.

I don’t want you to forgive me for my tone. Instead, consider joining me. Getting judgemental about things that boost and sabotage your career is a good idea.

For practitioners who apply psychology, their work will only be as good as the behavioral systems they employ. Build on the best evidence, and you have the best chance of success. And with your successful products, they will raise your career.

But there’s a catch. If you fall for behavioral pseudoscience or build on discredited psychology, then most of what you create will follow the adage “garbage in, garbage out.” And the more you deploy dysfunctional products, the more you may feel their weight pulling down your career.

Behavioral science doesn’t just help you build better products and campaigns. It also helps you attract recognition, job security, interesting friends, and a fascinating life.

So, you should be judgmental, as pseudoscience will destroy your career, and the best evidence will help you build a fulling career and great life too.

Ready to become a behavioral taxonomy snob? let’s start judging.

Problem 1. Academic politics distorts psychology:

When I started reviewing behavioral science literature and systems, I quickly discovered that I needed to work across many academic silos.

My life would have been easier if each field had approached online psychology similarly. But they don’t.

Each field has its philosophy, way of framing issues, and jargon. Learning each field’s behavior change approach takes time because you need to enter their headspace to understand their literature.

The best quality taxonomies were usually from health. They often framed health behavior change in clinical terms, with taxonomies that sometimes look more like therapy.

Social marketing had the best practitioner taxonomies, usually in the areas of public health, safety, and environmental protection.

Human-computer interaction (HCI) had a radically unique set of principles, distinctly grounded in cognitive psychology.

Daniel Kahneman’s biases and heuristics were often circulated but they weren’t as popular in practice–probably because his early research was so technical that people struggled to connect it to practice.

E-commerce and marketers had another set of strategies. The Persuasive Technology scholars has a truly unique literature, and there were many more.

You’d often find critical behavior change principles that only existed in one area. Source credibility was all over the persuasion literate but virtually missing from health. HCI had so many product design concepts like usability, simplicity, and findability, which were missing from other fields.

And to make matters worse, many of the behavior change taxonomies were so theoretical, that you’d often struggle to make the link between theory and practice.

Many are unaware that a good number of behaviou change scholars, have never once worked on the front line implementing behavior change programs. In other cases, they were specialists in applied psychology–especially the social marketers. So behavior change principles could range from proven tactics, to untested speculation.

However, if you’re a cross-disciplinary behavioral scientist, navigating the clutter is your job. So here’s a summary of what you have to manage, when crossing academic turf.

The same or similar principles may be repackaged with different jargon; we’re told they operate by different theoretical rules; they’re missing mission-critical factors. Even if you believe principles are blatant duplications, pushing this can trigger a viscous backlash, as cutting redundancy also means that someone may lose their reputation, and job security.

Politics is real. Welcome to humanity. When crossing academic silos, our job is to recognize the politics, understand how it distorts the science, and just manage it.

Problem 2. Mixed principles prevent research:

Most taxonomies are so messy that they provide mashups of principles instead of each distinct principle.

This is ok for product design but you can’t use these taxonomies in research. When studying what drives behavior, we need taxonomies of distinct principles, which allow us to identify what works and what doesn’t. If your taxonomy mixes principles, then you won’t know which of the principles matters.

We call these essential principles the kernels of behavior change, the core principles, the essence, etc….. If you divide these principles further, they stop working. They’re the smallest principle that can influence how people think, feel, and act. Break the smaller, and nothing is left. Combine them together, and now you have a mashup of separate principles.

Let’s say a taxonomy has the principle of a public pledge. We can break this into goal-setting as principle 1, and social facilitation as principle 2. What the author described as one principle, we can see as two.

Obviously, I just made a subjective judgment here–not very scientific of me. If I were making this call in a formal research setting, I would have a taxonomy of principles, that I may use, and compare my judgment with others. But this is just an example.

Unfortunately, many of the taxonomies present mixed principles, rather than distinct ones. This leaves you stuck splitting them apart if you need them for research. It’s not a deal breaker; it’s a pain in the butt. It makes many taxonomies are harder to work with.

Problem 3. Managing discredited and bad science:

Some taxonomies contain principles the authors invented based on speculation, shoddy research, or small sample sizes.

Consider all the psychological studies that have failed replication, including entire chapters of “Thinking, Fast and Slow.”

Or how about the behavioral economics theories that rely on the discredited link between glucose and ego depletion?

Or what about the recent academic fraud claim, by behavioral economists, who used fake data to “prove” that placing an honesty pledge at the top of a form matters?

And worse, once an area of science gets discredited, the authors rarely issue retractions. Sometimes, they continue promoting discredited science for years.

Why has there been no update to “Thinking, Fast and Slow” given the many studies that failed replication?

Why does the media keep pushing the hooked-on technology myth when scientists have consistently shown for over a decade, that addiction psychology does not operate in social media as they claim?

Making matters much worse, many schools buy their behavioral science content from instructors who produce video lessons, get paid, and move on. Even when the content has been fully discredited, some schools teach discredited psychology for years. I won’t name names, as I’m in a conflict of interest here, but it exists.

For these reasons, you should never fully trust the scientific literature. Even if you have strict standards, there’s always a risk that lousy science may enter your work.

I managed these risks by only including principles with replication, limiting my sources to high-quality research, and a bunch of other routine practices.

However, I had to lower my standards at times. Take, for instance, HCI and UX. Using behavioral science in unusable products is insane. You can’t nudge someone to leave a locked room.

HCI and UX principles are prerequisites for behavioral science. However, due to underfunding, there’s not a lot of great HCI or UX research.

I taught in the iSchool at the University of Toronto, in their UX Masters Program. This is an elite HCI, PhD track program. But most of the content came from interactive design books, not peer-reviewed scientific papers. This isn’t ideal. But it is what it is.

We cannot reject underfunded research in our attempts to dodge bad science. So I had to lower my standards to incorporate promising research and underfunded research.

It’s only when you learn to sidestep the nonsense and travel to the edge of credible science that you realize how little we know. My PhD did not crown me as the fountain of of profound truth. Instead, it gave me the confidence to stand on stage in front of thousands and say with confidence, that I don’t know — and neither does anyone else — but here is what we think might be going on.

Sometimes, we must include lower-quality research and manage ambiguity. Of course, this introduces risks to our research. Here’s how I typically manage this:

First, by making transparent disclosures about my confidence in the evidence. The community will value your research if you provide honest assessments of its reliability. Acknowledge your limitations and never project more confidence than your evidence permits. If you identify an important gap in the literature, share it, as it may inspire someone else to fill the gap.

Managing bad science makes our job more difficult. And in behavioral science, this is part of the ride.

Problem 4. Funding biases behavioral systems:

Research funding has a massive impact on behavior change taxonomies. This is why health behavior change taxonomies usually have the highest quality and most evidence. It’s also why the best practitioner guides typically come from health behavior change.

The downside is that once you leave health, research quality usually nose-dives, sample sizes shrink, and replication is harder to find.

However, other fields like international development, environmental protection, and public safety, for instance, are moderately funded. But other important areas like UX and visual design can be so underfunded that the science feels too skimpy.

This is why my early research was so health-focused, and why I developed a comprehensive system of behavioral science that was hard to use. The moment you adopt high scientific standards, most of your qualifying studies are from the health field.

Though I developed a comprhensive system, I wasn’t able to identify numerous psychological principles, because health behavior chagne specialists didn’t know these principles mattered, and didn’t report them.

So again, our challenge is to give underfunded research a fair chance, but we have also have to block psudoscience from slipping in, because once the standards drop, who know what may make it in.

All behavioral science systems that integrate vast areas of science carry this risk. Again, this is just how it works. The point is that we understand how research funding biases the science and then develop street-smart strategies for managing it.

Problem 5. Hyperinflation of redundant principles and practices:

Perhaps one of the worst situations in behavioral science is the perpetual “discovery” of new nudges. Often, these are merely repackaged old principles or tactics that the author failed to recognize or possibly ignored.

Perhaps “publish or perish” exerts such pressure on scholars to find something that they sometimes fake their data. Behavioral economics literature is so overloaded with redundant principles, debunked theories, failed replication, and now,fake data.

I am so distrustful of behavioral economics claims that I won’t approach many of their systems without scrutiny. Cognitive biases are real. They are legitimate faculties we target in behavioral science.

My issue is this: scholars keep inventing biases that don’t exist because they’re just reframing another principle and passing them off as a new nudge.There’s an entire online lecture with a scholar repackaging Cialdini’s framework as a cognitive bias system! If you’re into theft, at least hide your crime.

But what’s most confusing is that many cognitive biases don’t meet the criteria for being a cognitive bias. Look up the scientific tools that are typically used to measure cognitive biases. You’ll see that they usually look more like IQ tests, assessing reasoning, math, logic, spatial memory, etc. A cognitive bias is a cognitive assessment without objectivity.

And if you think that behavioral economics introduced the concept of rejecting rational decision-making, you might want to reconsider. Recently, I encountered a historical account that claims behavioral economics revolutionized behavioral science by getting us to reject rational decision-making models.

We OGs, who’ve been in the field over 25 years, know that this claim is delusional. Never in my career have rational models dominated. In Social Marketing 101, rational models are usually trashed in the first few minutes. Social marketers, not behavioral economists, were the ones who got governments to adopt irrational views of human decision-making.

About 13 years before “Nudge” was published, Prof. Doug McKenzie-Mohr summarized this view as follows:

“The ‘rational-economic model’ of human behavior, upon which the RCS was based, erroneously assumes that individuals systematically evaluate choices, such as installing additional insulation to an attic, and then acting by their economic self-interest. … How effective have social marketing campaigns been that have been based on this model? Not verry”

McKenzie-Mohr, D, and W Smith. Fostering Sustainable Behavior — An Introduction to Community-Based Social Marketing. Gabriola Island, Canada: New Society Publishers, 1999.

Let’s go back further in time. Consider the Elaboratoin Likelihood Model, from the 1980s, which explains when decisions are more rational or irrational. Behvior change practice has always had irrational factors, going back 2,000 years to the time of Aristotle–who also advocated using falicies in persuasion, yet another set of repackaged principles that today, we call cognitive biases.

The lesson here, is that an entire academic field can believe an account of history that has no grounding in history.

They can develop behavior change principles, theories, and practitioner frameworks, all adapted from other fields, with no credit to the source, contributing to a big, confusing mess.

Unfortunately, this is our reality, so let’s discuss how to manage it.

The best strategy for cleaning the clutter is a simple literature review. If you hold out for replication and a consensus of evidence. No matter how messy the science, synthesis helps you see what matters most.

Unfortunately, this is easier said than done. A literature review can take days to weeks, depending on the scale. And if you’re dealing with significant duplication and high scientific standards, it can take years.

Here’s why. Without years of front-line experience, you won’t even recognize common concepts even when you’re staring right at them. That’s why big synthesis projects require domain experts from multiple fields.

Fortunately, there’s an easier solution. Just prioritize large-scale systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or various data reduction research papers. These types of studies can take years to complete with teams of experts. They give you the birds-eye perspective, so you can avoid the chaos.

Some behavioral science taxonomies are built from synthesis research–like the IBCM, so they’re a great shortcut for focusing on what works.

But also, it’s crucial to avoid research that magnifies complexity. Take, for example, the massive cognitive bias wheel, with over 100 biases. While some might find this beneficial, I disagree.

The most effective behavioral science tools prioritize core strategies rather than a gazillion synonymous tactics. In behavioral economics, several data reduction studies have already reduced the exploding biases to manageable lists.

Despite this, people still push dysfunctional mega-lists of redundant cognitive biases, even when there are high-quality synthesis studies that have already helped us pinpoint the few biases that matter most.

As my final advice on surviving the duplication, learn to differentiate between low-grade systems with thousands of tactics versus taxonomies that distill the core drivers of behavior.

And please start crediting the Social Marketing scholars because this is where our field came from.

Problem 6. The best models are too narrow for general use:

The best behavior change systems explain behavior at multiple levels, providing both a behavior change theory and taxonomy.

Consider, for instance, Prochaska’s stages of change model. Its macro-level stages define how people change through stages. But it also has a list of principles that move people through each stage.

Prochaska’s model functions more like a behavioral theory, where stages impact principles, and the principles influence stages. It’s so robust that one can reasonably predict which behavior change principles to use based on a person’s stage.

Prochaska’s work inspired me with the idea that a large behavioral taxonomy could operate at multiple levels, with proven linkages between principles.

I incorporated principles from Prochaska and other similar frameworks. I had to manage the problem of their principles being too focused, but they all became more generalized as the system progressed.

But the main thing, is I took Prochaska’s work as inspiration for what one should strive towards, when developing a behavior change system.

Systems like this are excellent for product design.

There are probably more health behavior change products based on Prochaska’s model, than any other. I spent two years measuring the impact of behavioural models, and Prochaska’s model was as close as you get to guaranteed impact–so long as you don’t botch the implementation.

The downside is that they tend to be extremely narrow. They offer the highest behavioral impact, but only in extremely narrow contexts.

If they fit your application, you should consider them. But if not, keep theory shopping.

Problem 7. Author-curated lists don’t explain behavior:

What’s counterintuitive is that many behavior change taxonomies are arbitrary lists, without any unifying theory. Beyond their principles, these systems do not explain behavior.

I’ll define a behavior change theory as a set of principles that work together, creating effects greater than the sum of their parts. For example, take “Carrot and Stick”. It effectively doubles motivation by offering a reward for compliance and a punishment for non-compliance. Neurobiologically, each principle invokes a distinct motivational system.

However, numerous behavioral taxonomies are more like author-curated lists that tell you how to influence without explaining why it influences. Here are a couple of examples:

First, as a Canadian, I started my career using the Tools of Change taxonomy (https://www.toolsofchange.com), an excellent system of environmental social marketing.

Taxonomies like this often use paint-by-numbers formulas. For instance, Step 1 — Identify audience needs, Step 2 — Eliminate barriers, Step 3 — Add your social normative influence here, and so on.

Although great for education and introductory behavioral design, they’re not great for scientific research.

Second, consider Cialdini’s 6–7 principles. Systems like these tend to be extremely arbitrary, featuring principles the author handpicked without any clear justification. As far as I can tell, there is no scientific merit behind the decision for 6–7 principles.I assume it was a tradeoff between research and keeping it short enough to sell books.

However, there is no theoretical rule or statistical method that I can use to verify that Cialdin’s principles matter most. In the Big-5 personality system, if I follow a standard method, there’s almost a 100% chance that I will arrive at the same personality traits, in any culture, any language, and any sub-population of people.

In studies of source credibility, I can do the same and discover which personality qualities drive trust.

In studies of social influence, I can also use similar methods to distill common principles of social psychology that operate in distinct ways.

In an empirically grounded behavioral system, research tells you what is real. In a theory-grounded behavioral system, rules shape the content. But in an author-curated list, the author can cook up whatever they like.

Worse, Dr. Stibe and I ran a study and compared social proof with other principles of social influence. No matter what we did, social proof always dissipated when mixed with other social influence principles and always merged into normative influence. Many scientists say social proof does not exist and that it is a social norm, exactly what our research also showed.

I’m not trying to trash the competition. Instead, I’m trying to bring a behavioral science perspective to behavioral science. Let’s review the pros and cons.

On the upside, these lists are as good as the author’s talent. Viewing them as recipes — rather than explanations — enables us to appreciate them as the author’s advice.

I started with Jay Kassirer’s Tools of Change, as a helpful set of recipes that helped me start out. It’s not a tool for understanding behavior. Instead, it’s a formula for shaping it.

Likewise, Cialdini is a slick salesperson. Rather than seeing his system as the truth of persuasion, I see it as his sales formula. It’s grounded in his understanding of psychology, tied to his experience translating those principles into practices. While Solomon Asch may be able to tell you everything about how social normative influence works, Cialdin can show you how to use it to sell used cars.

Though I’ve been harsh on his packaging and jargon, it’s still a good collection of principles. So, I use his system in teaching, but just for introductory lessons, and then I move to more detailed models.

On the downside, author-curated lists are arbitrary, often with vaguely defined principles, and detached from theory.

In the worst case, pop-psychology practitioner lists can be very separate from reality and harmful if they get you to focus on things that don’t matter, and exercise bad judgement.

If you build a 21-day habit app, and the best evidence suggests you need 66 days to form a habit, you may miss the mark. If you believe it’s good to trap users into long-term proprietary products, and many users avoid dark patterns like this — then you’ve adopted a psychological model that you may come to regret.

So, use author-curated lists with a bit of caution, and if you’re pilot testing your products, you’ll probably smooth out problems. In research, these can be a bit funny to work with, but they usually take you deep into practice and sometimes reveal something new.

In IBCM, Aristotle goes Web 2.0

Let’s return to my original study. I did not want to build a massive taxonomy of behavior change principles. I had no other option.

Over 6–12 months, I pooled around 240 principles with solid evidence behind them.

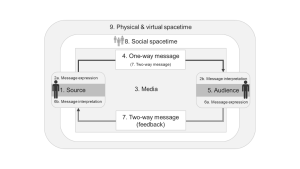

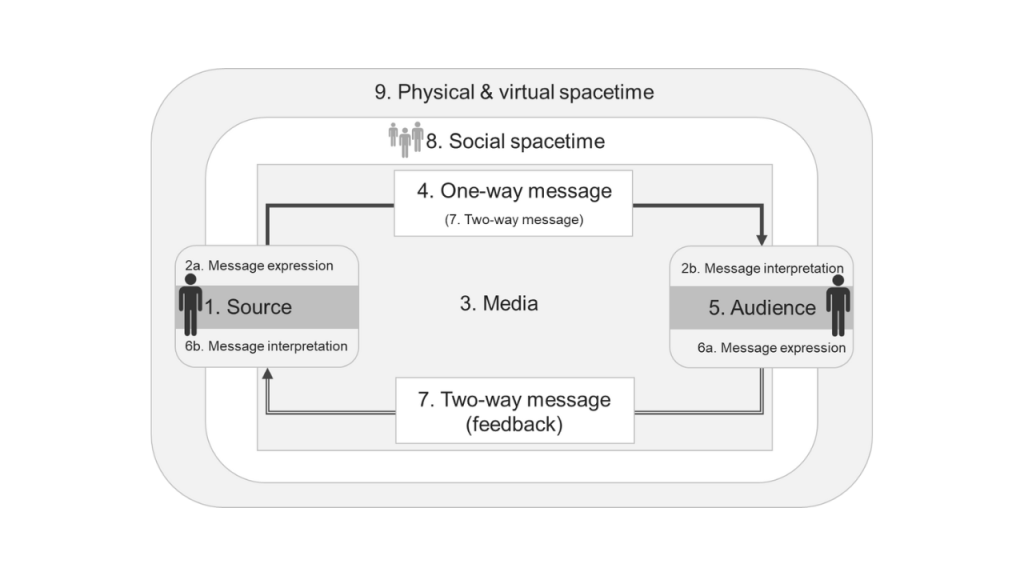

At some point, I started arranging the principles by Aristotle’s 2,000-year-old persuasive communication model. This may sound odd, so let me explain.

Early on, if you wanted to study web-mediated psychology, you had two main options. Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) studied how people use technology. But Persuasive Technology studied the opposite, how technology uses people.

What’s less known, is that ancient rhetroicical frameworks were popular among the early Persuasive Technology scientists. This meant that Aristotle and Cicero were core reading if you wanted to learn how to influence people online.

Aristotle’s 2,000-year-old persuasive communication model had a source, that sends a message to an audience, who is influenced by that message.

In 1997 when I started running online behavior change program, public health officals used the one-way communication model. They used to call it “point and shoot” influence. You shot a persuasive message bullet, that went into your target audience, who would then be influenced by your persuasion bullet.

The early days of the World Wide Web were largely static, dominated by a one-way, point-and-shoot communication model. This is what we call Web 1.0. We used to call crapy websites, brochures. Because most websites were like company flyers.

In Web 1.0, Aristotle’s one-way, point-and-shoot communication model was perfect. In behavior change, we often use one-way models. So it’s probably no surprise that Aristotle’s framework worked extremely well in the frist decade or so.

Slowly over time, the web became more interactive. People started using more interactive design strategies, and eventually, we reached Web 2.0 when two-way communication dominated. This is when interactive social media and database-driven products started to dominate.

While Aristotle’s model was great for Web 1.0, it was too limited for Web 2.0 behavior change. And this is why I started researching the link between interactive communication theory and behavior change.

What emerged was a communication framework that I published in 2009, and then recently republished an update named, “The Interactive Behavior Change Model”.

In this model, we are the source, the company, brand or product. We, as the source, send our messages through media to the target audience.

We usually design for specific faculties in our target audience, including their perception, cognition, emotion/motivation, decision making, trust and behavior.

If we’re going Web 1.0 style, we’ll take a one-way approach, where we formulate our most persuasive message, and then “spray and pray”. The thing with true one-way messaging, is you never fully know how it’s performing, and you don’t even know if your message is relevant to your audience.

However, if we have a feedback channel, we can use two-way communications, which unlocks the best behavioural principles avaiable. With a feedback channel, we can use tailoring, personalization, and reinforcement learning, expanding our theoretical design options to include cybernetic adaptive AI systems, gamification, coaching, and control theory loops.

To enhance our efficacy, we’ll leverage the impacts of message encoding, where style can overshadow substance. Here we dress up our messaging with aesthetic styles that enhanced our message impact. We encode our message, in a way that our audience will docodes it. This is how we make things simple, intuitive, and instantly understood.

The media is anything we use to communicate between one conscious agent and another. It is not the message, but its form shapes the message. And the media is something that can only be transmitted through sound, vision, tactile signals, and any other sense.

At its most elemental form, communication is signal transmission, which is why, in this model, everything I discuss for websites and apps equally applies to interfaces for the blind, deaf, and even direct brain-to-brain communication. While the technology is not yet here, IBCM is already the only behavioral science system designed for every conceivable media by which humans and AI can interact.

We’re not done, because we can also boost the impact by leveraging our hard-wired social predisposition. As Dr. Stibe’s research shows, there is one principle of social psychology that we can use like a switch, to turn social influence on and off. It’s called social facilitation. All we need to do is make people aware of the presence of others, and next we can curate a custom formula of distinct social influence techniques that we may leverage for added impact.

And finally, the physical and virtual context offers a final area of psychology that we may layer. We can integrate the limits and abundance in time, space, to boost our impact. Principles of scarcity and abundance work for things (space) but also for time, and just by playing with the environmental context, we can make our products that much more effective.

And this is why communication theory matters. It changed everything.

But I still had to boil down the messy science to its core essence–a job from hell.

Identifying the core principles of behavior change

There was so much duplication, redundancy, and misleading jargon that I was drowning.

It was so insane.

Then, finally, a hero arrived to clean up the mess, and her name was Prof. Susan Michie.

While many know Prof. Michie’s work for the wheel, few know where the wheel came from and why her work was so important.

If you think I’m a snooty whiner, you haven’t read Susan Michie’s early work. She was viscously brutal on the situation–and rightfully so, because our field was a dysfunctional mess.

Nobody could have cleaned up the mess on their own. Prof. Michie was wise, because her early work brought together many stakeholders for collaborative research and consensus-building exercises.

In one pioneering paper, she conveyed numerous behavioral scientists, who reduced over 100 theoretical principles to a manageable shortlist.

In another series, they developed the best health behavior change taxonomies available, with distinct principles, clearly defined, that were all backed by good evidence.

This was the biggest cleanup job in behavioral science, but many forget that this was only limited to health.

No other field has done this, which is why many areas of behavioral science are still theoretical disaster zones. They all have their heroes trying to clean up the mess, but in most areas, the pollution flows faster than the cleanup.

Anyway, I reached out to Prof. Michie, who was kind enough to share the pre-publication taxonomies. It was a geat taxonomy, addressing many of the problems we discussed previously.

I started integrating this research with taxonomies from persuasive technology, social marketing, consumer psychology, cybernetics, human-computer interaction, various visual design principles, and many other fields.

What was good about my communication-theory approach is that my personal opinions don’t matter. The rules of communication theory dictate which principles go in which domains. It was my job to understand the domains and categorize the principles.

My first attempt was ok, but it took years, various scientific collaborations, and numerous projects before the links were solidifying.

But what I had at the time was good enough for the study.

Emotional relationships with technology

One may complain that communication theory is as arbitrary as any other organizing principle. Why not organize all the behavior change principles with a pyramid, box, or abstract art? Why not a pig?

The prior papers cover the theoretical and practical advantages.

But this is the story of discovery.

So, let’s explore the most counterintuitive reason, the IBCM’s most critical premise.

When I began my doctorate in 2006, many thought that psychology didn’t work online, while others believed there was some special media psychology that eluded discovery.

Overall, the belief was that online psychology had rules distinct from human-to-human psychology. This meant that a sales pitch delivered by TV operated on a set of principles distinct from the same pitch delivered by a person.

With this as the dominant view, I started my doctorate on a wild goose chase, hunting media psychology that didn’t quite exist.

There was much more to my first journal paper than measuring credibility and behavior. The real contribution of that paper is that I compared how two psychometrics operated on websites. The first was a tool that described computer credibility. The second was a tool that described human credibility. With this, I could test the theory that human models of psychology worked equally well on technology.

My main takeaway was that engineering software using human psychology was fair game. This paper just one of many that showed this same trend in the science.

And this is what’s extremely important. For most studies of human-to-human psychology, you can swap out one of the people, replace them with technology, and in most situations, there is no psychological difference.

While many thought I was a head-case for pushing this ideas, this was routine knowledge among the persuasive technology scientits. Specifically, this was BJ Fogg’s area of research before he ventured into behaviorism and then entered personal development. There are decades of research here, which I’ll cover in the upcoming book.

To help you better understand this idea, consider this:

Most people don’t think about their digital products as something that can form a reputation, be trusted, or be disliked.

They don’t believe that consumer-brand relationships can be manipulated with the same oxytocin tweaks we use to manipulate human-human relationships.

They don’t believe we humans interact with technology as though it were another human.

They pass off anthropomorphizing as some absurdity to be ignored.

When people respond to software like a person, many scientists comment on it as an odd afterthought they can’t explain. Yet, these snarky comments litter the scientific literature.

How did they get there? I’ll tell you: human nature.

Consider this:

A good sales landing page employs many of the same strategies a good salesperson employs.

A health coaching app replicates the same principles used in human-driven coaching.

A charming cloud product makes users feel welcomed, just like a charismatic business operator.

Ask yourself these questions, and give yourself a point for every yes:

- Can people feel insulted by rude computers?

- Do you feel good when complemented by algorithms?

- Do you feel appreciated if an app expresses gratitude to you?

- Can people fester lifelong distrust against brands whose staff lie?

- When you distrust a brand, do you treat its flattery as manipulation?

- Have you ever resented a company because of their staff?

- Do introverts dislike using software that speaks like an extrovert?

- Can we leverage social influence in digital media just by raising awareness of others?

- If you saw an aviator get electrocuted, would you experience a stress response?

- Does your brain measure your social status in video games using the same geometry for calculating real-life social status?

If you give enough yeses or maybes, these ideas should feel intuitive. If not, I urge you to explore the science surrounding this topic.

What’s counterintuitive is that we humans respond emotionally to technology, similar to how we respond to others. We are pathological anthropomorphizers.

For this reason, we can build websites, apps, and AI agents that build on this human trait. We can architect our products along the grain of human psychology to create superior digital products.

This is how we can fuse all the classic behavior change strategies with design psychology, social influence, and more, then integrate them with a personal touch that fosters an emotional connection with our users.

Clifford Nass is perhaps one of the most important scientists who studied this phenomenon. Before he passed away, we were connected on LinkedIn. I once noticed that he was hyper-connected to people working at Apple, with almost no connections from Microsoft.

If you ever wondered why Microsoft consistently copies Apple’s tactics, without understanding their strategies — then this may very well be one of the key psychological differences.

Realizing the benefits of this approach, I submitted again to the Persuasive Technology community. The reception was wonderful, and many of the field’s leaders encouraged me to develop the model further.

Reverse engineering digital psychology

With a solid theoretical structure and a decent list of principles, my next step was to carry out the study and see what emerged.

I used a method called statistical meta-analysis. This is the gold standard of science, the most credible method we have for synthesizing trends in the scientific literature.

Earlier, I complained that pseudoscientists cherry-pick whatever science validates their absurd beliefs. In contrast, cautious scientists hold out for meta-analyses or systematic reviews, which find the consensus in the science. Additionally, they show trends across papers, reveal bias, and even discard low-quality science.

So, by using statistical meta-analysis, I could distill what really mattered in online influence. The way it works is you dig up scientific papers, use the taxonomy to identify their behavior change principles, extract the impact metrics, and then merge them together.

So, what emerged?

The best psychological design pattern combines two separate strategies, that fit with Prochaska’s stage model.

In step one, users would complete a brief Cosmo-style quiz, built on the Extended Parallel Process Model — something I call the clinical fearmongering model. With this model, you’d scare the user into joining a larger program by telling them they were at risk of being an alcoholic, addict, heart attack victim, etc., and then layer on the self-efficacy with a message of hope, encouraging them to join your larger program. When viewed from Procahska’s perspective, this step would shock someone out of denial, getting them to think about changing.

For step two, if you could get them in the larger program, that’s when Prochaska’s stage model or Cognitive Behavioral Therapy would take over. I won’t delve into details, but regarding the behavioral principles, they all were coaching-like structures, with education, goal setting, feedback, support, and reminders. However, products without reminder systems rarely worked, and those with ultra-aggressive reminders were very effective.

Bootstrapping IBCM locks it up

My oral defense went well, and I was awarded my Ph.D. About a year later, JMIR, the world’s top e-health journal, published my study: https://www.jmir.org/2011/1/e17/

My next step was to finalize the IBCM and share it with the scientific community.

But things didn’t go well.

I applied for research funding over five times in a row and couldn’t raise a cent in Canada. It didn’t matter that I was applying with partners from the University of Toronto, the Center for Global e-Health Innovation, Bridgepoint Health Hospital, The Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, Evolution Health, and many prominent scientists.

People kept telling me that CIHR, Canada’s health funding agency, was corrupt and that unless you had insiders lobbying to give you money, you had almost no chance. Eventually, I started to believe the accusations of corruption in CIHR.

Under no circumstances will I waste my time competing in a fixed match. If I don’t have an equal opportunity to compete on merit, then forget it. I would have continued for decades in a fair contest. But not one where who you know matters more than what you are offering.

And so, I wrote to the research team, saying I did not believe the system was fair, and would not waste my time in a fraudulent contest. I told them my plan to share the work in a book and move on. My friends were shocked but supportive.

While working on the book in 2011, I decided to run a few classes and fine-tune the content. What happened next was a shocker.

My courses kept selling out, and people started traveling worldwide to attend my training. In a few years, I was traveling across Canada, the US, Europe, and the Middle East.

The money sarted rolling, and I put it into the system. I advanced the models through consulting, teaching, and numerous research collaborations.

The ultra-brilliant Dr. Kerr pushed me to improve the motivational parts of the model, leading to my dive into the neurobiology of emotion, personality, and behavior.

https://www.linkedin.com/in/gilliankerr/

This opened my collaborations with Dr. Leo Restivo, a neuroscientist who shared my passion for computational linguistics and predicting behavior.

We developed the Emotion-Behavior model, a teaching aid that covers the neurobiology of perception, cognition, emotion, and behavior. Years before Robert Sapolsky’s “Behave”, my school was out there teaching behavioral biology for digital products and marketing.

https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=fjFf8boAAAAJ&hl=en&oi=sra

With Dr. Stibe, I ran multiple studies. Our collaborations on social influence were key to IBCM’s development, as this approach allowed us to let the research tell us how to construct the model. We carried out research on dark patterns and how behavioral science backfires–a topic so taboo, that some informants feared reprisals for speaking with us.

https://www.linkedin.com/in/agnisstibe/

With Dr. Chandross, we developed scenario-based learning games for Elections Canada and the Canadian Military. These educational approaches were so successful; I can quickly bring newcomers to the same level of judgment that behavioral scientists develop at the master’s or Ph.D. level.

https://www.linkedin.com/in/david-chandross-ph-d-92a01234/

I also ran numerous technology projects, with a suite of IBCM psychometric tools, that I used to optimize the model, and also, deploy a fully automated behavioral science AI product. I use some of these in training but hope to launch the automated AI platform after the books.

My students transformed the IBCM in many ways.

But unfortunately, my company, AlterSpark, bootstrapped the IBCM, which made it somewhat proprietary. This was not my intention.

That’s why I’m now putting its tools under a flexible Creative Commons license.

I’m backlogged on publishing a color psychology book first, and then, right after, I want to publish a book on the IBCM. I already have around 400 pages with several editing rounds, so 2024 is possible.

Follow me on social media if you’d like to get the resources as I release them.

I provide the full system in training, if you’re interested in that path.

Hope you’ll have an easier time navigating the insanity of behavioral science.

Chao for now.

Brian

IBCM Citations

These are some of the core scientific papers that tied to the model.

Cugelman, B., & Stibe, A. (2023). Interactive Behavior Change Model (IBCM 8.0): Theory and Ontology. In International Conference on Mobile Web and Intelligent Information Systems (pp. 145–160). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/373530823_Correction_to_Interactive_Behavior_Change_Model_IBCM_80_Theory_and_Ontology

Cugelman, B., Thelwall, M., & Dawes, P. (2009). Communication-based influence components model. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology (pp. 1–9).

https://wlv.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/2436/85973/Cugelman_%202009_communication-based_influence_components_model.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y

Cugelman, B., Thelwall, M., & Dawes, P. (2011). Online interventions for social marketing health behavior change campaigns: a meta-analysis of psychological architectures and adherence factors. Journal of medical Internet research, 13(1), e1367.

https://www.jmir.org/2011/1/e17

Cugelman, B., Thelwall, M., & Dawes, P. L. (2009). Dimensions of web site credibility and their relation to active trust and behavioural impact.

https://wlv.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/2436/85974/?sequence=4

Stibe, A., & Cugelman, B. (2019). Social influence scale for technology design and transformation. In Human-Computer Interaction–INTERACT 2019: 17th IFIP TC 13 International Conference, Paphos, Cyprus, September 2–6, 2019, Proceedings, Part III 17 (pp. 561–577). Springer International Publishing.

https://inria.hal.science/hal-02553864/file/488593_1_En_33_Chapter.pdf

How to navigate the insanity of behavioral science was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.