Would you believe UX thought leader Jared M. Spool once carried out an unorthodox exercise with the following questions:

What would make this product evil?

I want you to come up with ways we could make the design much worse.

How would we make a truly horrible experience for the user?

What followed was a series of activities that led the participants to map out the user's journey through hell. More importantly, it was an introspection made possible because any of us has been through such a scenario. Thus, in a way, it was an attempt to build empathy, but in a fun manner.

Whether it was a flight delay that led to an overnight stay at the airport hotel or the regretful mistake of spending on a product that you didn't want, we all went through not just a bad experience but a terrible one. Psychologists have coined the term negativity bias to show that humans pay more attention to or give more weight to negative experiences than positive ones.

Wrestling with Doom Loops

While an expert facilitator like Spool may guide the simulation to lead them into identifying neutral attributes, very often we fall into a vicious cycle. A common phrase in the business world known as "firefighting" comes to mind. This term doesn't refer to a heroic act to save someone from a natural or man-made disaster. Rather, firefighting in the business world is the practice of dealing with problems as they arise rather than planning strategically to avoid them. The compounding of these problems leads to bigger, more horrible problems, and the vicious cycle is complete when the team is perpetually fighting a growing fire.

Writer Jim Collins refers to this as the "Doom Loop" effect, as he wrote one of the Time lists of The 25 Most Influential Business Management Books, Good to Great. This is a situation when one negative action triggers another, which in turn triggers another negative action, continuing the cycle. The implication is a continuous downward trend that becomes self-reinforcing. At this point, it may be tempting to associate the doom loop with the business context, but an astute designer can take this concept and apply it to a customer's experience. Observe the following true account:

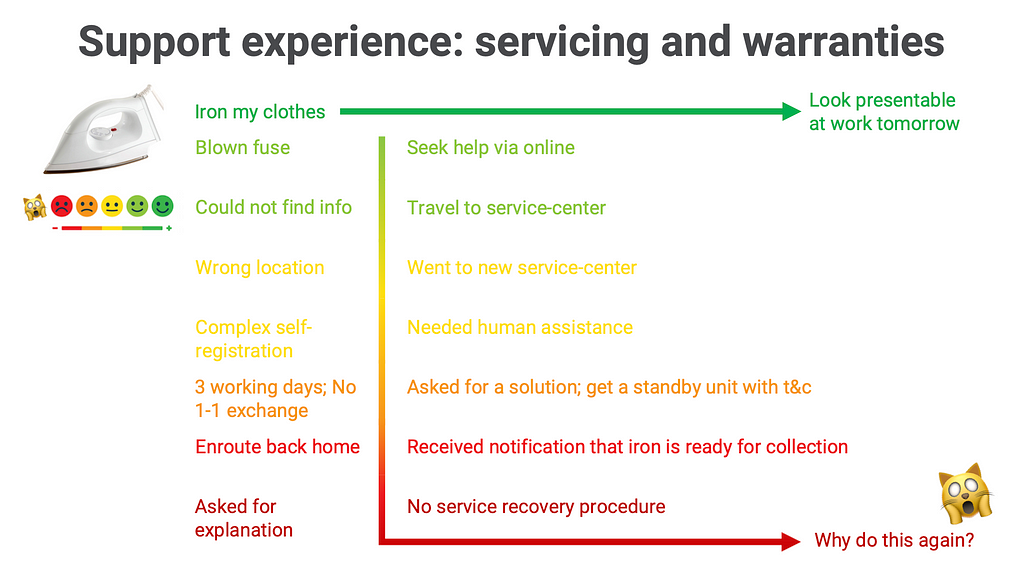

Work requires me to look presentable with my shirt ironed. The problem was that my iron stopped working the day I needed it. I tried to seek help on the website, but I could not find any relevant information or solutions.

This led me to travel to the service center, only to realize that the service center has relocated to a new venue. Grudgingly, I went to the new service center. Only to be met by a complex self-registration trying to pull my personal data from various platforms. A reluctant customer service representative came out to assist with my self-registration. He went on to state that there were three working days with no direct replacement of the iron. Given that I needed to iron my shirt immediately, I wasn't given a solution until I asked for it the third time. When the service rep brought the additional standby unit, he stated the list of terms and conditions on using the spare unit, which include penalties for misuse (why would I do that intentionally?).

Finally, as I was on my way back home with the spare unit, I suddenly received a notification. To my horror, the message stated that my unit was ready for collection. Flustered, I turned back, and instead of getting an apology or explanation, I was asked to sign a piece of paper to complete the support experience.

Would I ever go back to the service center again? The chances are very low, as there is an imprint of the horrible experience. To make matters worse, there were plenty of doom loops at every juncture, each repeating itself with different customers. Unlike my personal experiences, some other customers may have a worse experience. Over time, the accumulation of negative experiences felt by more customers eats away time from the same team to perform service recovery. At the same time, there would have been opportunities to work on more meaningful activities. They are opportunity costs.

Winning with CLV flywheels

Which is why recognizing another loop is paramount. In the book The Power of Moments, Author Dan Heath shared an experiment done by a Forrester researcher that got top executives to choose between two options:

- Eliminate all unhappy customers

- Elevate from passive to positive customers

The results were intriguing because these executives would share that their companies would spend 80% of their resources on option 1, but could have gotten nine times more revenue if they had put more resources into option 2.

Whopping nine times!

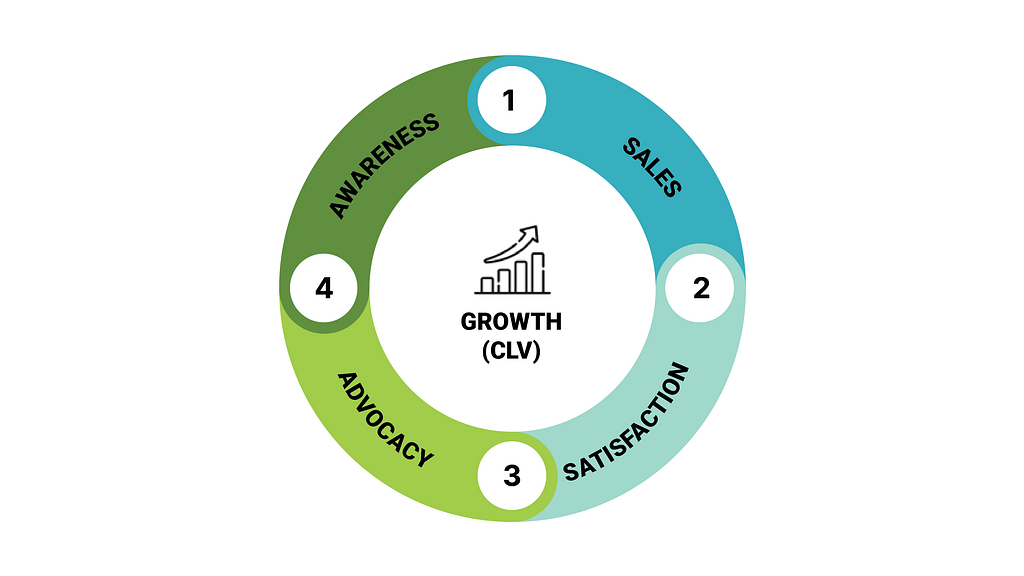

Our tendency to focus on negative experiences has prevented us from recognizing and seizing the opportunities of another loop. When left unnoticed, it misses out on a bigger opportunity. The good news is that another loop does exist that, when applied over time, creates momentum that generates positive returns, which it reinforces with each spin. This is better known as the flywheel effect, and the key ingredient is how success can be replicated through a series of logical but effective steps until it links as a chain.

2. Over time, customer satisfaction increases with usage.

3. At its peak, the customer shares and recommends the experiences to family and friends.

4. A new customer learns more about the products

5. Repeat to point 1.

We can see how one such flywheel could work:

1. The customer purchases the product as it meets their job to be done.

2. Over time, customer satisfaction increases with usage.

3. At its peak, the customer shares and recommends the experiences to family and friends.

4. A new customer learns more about the products

5. Repeat to point 1.

Well-known companies such as Amazon, Intel, and Cleveland Clinic have customized their own flywheels, but the general principle applies: persistent, gritty effort is needed to start the heavy flywheel before its own heavy weight begins working for you. The other is this: “The key is that you build it over a long period of time. The power of a flywheel is that it’s an underlying logic; it’s an underlying architecture.”

When time and customers come together, one experience metric comes to mind: Customer Lifetime Value (CLV). Known as a measurement to gauge the value of a customer across the entire customer relationship, CLV helps companies identify their best customers and replicate them. Not only would they continue with your brand, but they could also advocate for you through word of mouth or paid referrals. American Experience management company, Qualtrics, shares a simple formula on how to calculate CLV:

Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) = Customer revenue per year x Duration of the relationship in years – Total costs of acquiring and serving the customer

What makes CLV compelling for designers is its relevance to the designer's role in the organization. Simply put, in order to understand what it takes for a customer to part with their money over the product, left alone to maintain the relationships over a long period of time, a company needs to know why a customer would "hire" the product in the first place. Only by knowing the "whys" could a company move into a phase of designing the "whats" and the "hows", where the inputs of the designers and engineers come in. And by building over many “hiring” experiences, the revenue compounds for new as well as loyal customers.

Winning teams understand the importance of involving designers early in an innovative process. And despite the designer being a cog in the larger moving wheel and possibly playing a small part in the large organization, getting them to understand CLV, flywheels, and doom loops is important to establish a foundation between business and design. Just like how there are overlaps in the desirability-viability-feasibility (DVF) Venn diagram, so too are "builders of greatness", as quoted by Jim Collins, when they reject the "Tyranny of the OR" and embrace the "Genius of the AND". Rather than isolate business from design in two different silos, integrating both practices while recognizing the distinctive powers each offers is crucial for the success of the flywheel. The fundamental question is not only why but also who!

Who is on your team today? Are they open to collaboration and learning about how each team member contributes to the success of customers? Are the designers on the team uncomfortable with new concepts but keen to learn? Are the rest of the team members focused on the customer to work towards positive experiences and eliminate horrible ones?

I leave you with another flywheel from Jim Collin in his interview with Tim Ferriss:

“Fund and feed your next big curiosity question, which then leads to the research, which then leads to the chaos of concepts, which then leads to writing and teaching, which then leads to impact on the world, which then generates funding, which then allows me to fund the next question. Then, it’s perpetual.”

Let’s design our own flywheel systems.

Further readings

- Collins, J. (2001). Good to Great. Random House.

- Collins, J. C. (2019). Turning the flywheel : a monograph to accompany Good to great. Harpercollins Publishers.

- Ferriss, T. (2019, February 18). Jim Collins — A Rare Interview with a Reclusive Polymath (#361) — The Blog of Author Tim Ferriss. The Blog of Author Tim Ferriss. https://tim.blog/2019/02/18/jim-collins/

- Heath, D., & Heath, C. (2019). The Power of Moments. Random House Uk.

- Loranger, H. (2016, October 23). The Negativity Bias in User Experience. Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/negativity-bias-ux/

- Qualtrics. (n.d.). What is customer lifetime value (CLV) and how do you measure it? | Qualtrics. Qualtrics AU. Retrieved August 24, 2023, from https://www.qualtrics.com/au/experience-management/customer/customer-lifetime-value/

- Spool, J. M. (2019, August 16). Despicable Design — When “Going Evil” is the Perfect Technique. UI Conference. https://medium.com/user-interface-22/despicable-design-when-going-evil-is-the-perfect-technique-b0dba9aaa6cb

Unveiling the experience wheel of true fortune was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.