Memory, Image Theory, and the empty pursuit of certainty

Sometimes it feels like all we do is plan — and then plan for more planning. But what are the cognitive mechanisms we use to ‘plan’? and are they optimized for getting things ‘right’?

If we were optimized to be right, we probably wouldn’t be so quick to anchor to assumptions, hold our beliefs in spite of contradicting information, skew our perception of data, and default to following others over building our own convictions.

So what does this mean for planning? Are we good planners?

The reality is that certainty is an emotional state — it’s a feeling, not fact

As Dr. Robert A. Burton MD, a neurologist, explains in his book, ‘On Being Certain’:

“Despite how certainty feels, it is neither a conscious choice nor even a thought process. Certainty and similar states of “knowing what we know” arise out of involuntary brain mechanisms that, like love or anger, function independently of reason.”

In this post, we’ll talk about our desire for certainty, how we use mental images to create strategic plans, and the cognitive processes that help us simulate the future.

Our desire for certainty… a curse

If we define being ‘good’ at planning as things unfolding precisely as we’d expect until we ultimately achieve the exact outcome we articulated, then the answer would be no.

This isn’t surprising. We know there is uncertainty, luck, and factors outside of our control — yet we tend to build elaborate plans as if we need certainty (or even worse, think certainty is attainable). And technically, we do ‘need’ certainty.

Your brain craves certainty and avoids uncertainty like it’s pain.

— David Rock, “Hunger for Certainty”

In a 2016 study, researchers told some participants they would ‘definitely’ get an electric shock while telling others they would ‘probably’ get an electric shock. Counterintuitively, those who were told they would definitely be shocked exhibited significantly lower levels of stress.

Those who didn’t definitively know whether they would get shocked or not were measurably more agitated.

“A sense of uncertainty about the future generates a strong threat or ‘alert’ response in your limbic system.”

We actually have a biological reaction to uncertainty. It’s cognitively painful.

In fact, the part of our brain responsible for our response to stress and panic, the locus coeruleus, seems to play a significant role in how we manage ‘unexpected uncertainties’. This may seem somewhat intuitive, but this is separate from the areas of the brain responsible for risk and estimation uncertainty.

We tend to spend more time evaluating estimation and risk in plans than role-playing how we might deal with unknown unknowns. Why? This suggests the latter generates a panic response while risk mitigation and estimation provide us with that ‘certainty dopamine hit’.

Even though this desire for certainty drives us to avoid ambiguity, take on less risk, and inaccurately plan for an uncertain future, we have relatively powerful tools for imagining possible futures, crafting goals, and achieving previously unimaginable things.

As we’ve talked about before, this ‘against all odds’ level of conviction separates us from a rational, pure utility-based way of making decisions. In essence, one could argue (and many who study strategic decision making do) that it’s the irrationality, the conscious side of our reasoning, that enables us to thrive in uncertainty.

“Doubt is an uncomfortable condition, but certainty is a ridiculous one.” — Voltaire

When planning, we try to strike a balance between the two — we attempt to draw a picture of the future and imagine the paths that take us there… quite literally.

We strategize through mental imagery

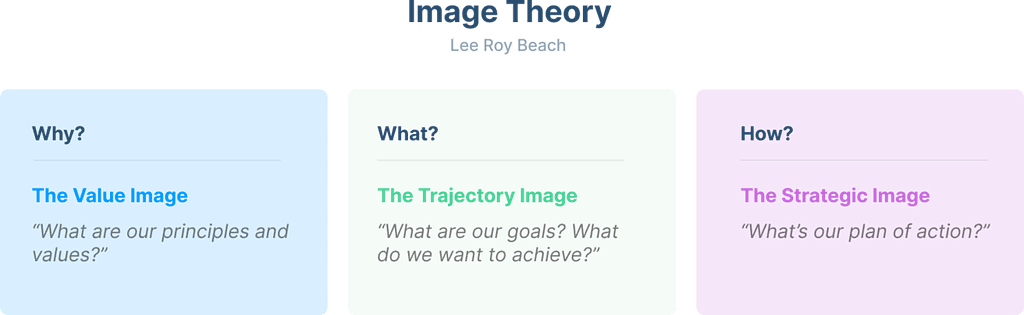

Image theory suggests that the construction of mental images is the way we primarily ‘plan’ and make sense of strategy. These images break down into three primary categories — the value image, the trajectory image, and the strategic image.

According to image theory, ‘plans’ are made up of tactics (the things we do to achieve a goal) and forecasts.

A plan is inherently an anticipation of the future, a forecast about what will happen if certain classes of tactics are executed in the course of plan implementation. — Lee Roy Beach

As Beach suggests, as individuals and as an organization, we’re constantly updating these pictures based on new information or ‘candidates’ (challengers to replace the existing principles, goals, and/or plans).

It’s interesting to think about planning in this way because we tend to use visuals as a medium for communicating plans — but how do we actually mentally construct and simulate future events?

This is something we do naturally and subconsciously, but the mechanisms we use to imagine our future ‘picture’ and construct scenarios to plan, set goals, and ultimately act, overlap with our memory recall.

We’re constantly time-traveling (mentally)

The human brain is a prediction engine. We’re constantly modeling our near and distant future based on our environment and past events to guide our choices. Many of these choices feel independent, but they’re often based on a lifetime of developed preferences and heuristics.

There’s a deep connection between memory and our ability to forecast and plan for the future. It’s a fundamental differentiator that separates human intelligence from other species (though apes have shown the ability to make some future-based decisions — at least from discounting perspective — see note at the bottom of the post).

The term ‘mental time traveling’ refers to this ability to construct the past, make sense of the present, and predict the future — all orchestrated by the same underlying cognitive processes. Though not identical, these functions do not operate independently.

When it comes to strategic planning, the term is episodic future thinking — our ability to imagine novel future events without experiencing them. The surprise to researchers (over the past 20 years) is just how much overlap there is between episodic memory and future-oriented simulations.

This is summarized in the ‘constructive episodic simulation hypothesis’:

Past and future events draw on similar information stored in memory (episodic memory in particular) and rely on similar underlying processes. Episodic memory, in turns, supports the construction of future events by extracting and recombining stored information into a simulation of a novel event. Such a system is adaptive because it enables past information to be used flexibly in simulating alternative future scenarios without engaging in actual behaviors, but it comes at a cost of vulnerability to errors and distortions that result from mistakenly combining elements of imagination and memory.

When we set goals, make predictions, and plan for the future, there’s very little distinction between those activities and episodic memory. When it comes to planning, this means that the same errors that plague memory, likely plague future-oriented thinking.

Memory itself is not optimized to present an accurate depiction of the past, it’s optimized to help us make sense of our environment and provide models to simulate the future. Researchers refer to this as constructive memory and there’s evidence that errors observed in memory recall, could also influence constructive memory.

Memory is not a simple replay. The bits of information that we recover from the past are often influenced by our knowledge, beliefs, and feelings.

— Daniel Schacter

For Daniel L. Schacter, this has been his life’s work — and he has an incredible summary of his work that was published in 2019. Like many of the other topics we’ve covered, particularly around strategic decision making, research on the overlap between past and future-oriented functions is still nascent.

Other really interesting resources that aren’t directly linked if you want to dig in more:

- A taxonomy of prospection: Introducing an organizational framework for future-oriented cognition (gets specific on the differences in future-oriented functions — including planning)

- Episodic Future Thinking: Mechanisms and Functions

- Decisions and the Evolution of Memory: Multiple Systems, Multiple Functions (a foundational paper often cited in this research)

This article was originally posted on 🔮 The Uncertainty Project

Note: on the argument about animals/humans and future decision making referenced above — it seems most studies on apes are based on discounting (decisions on current vs future cost/benefit), but there was an interesting study that humans are able to make similar decisions without the cognitive ability for mental time traveling.

Our desire for certainty can make us terrible planners was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.