The Extended Designer spends less time making products, and more time making progress.

2023 has been Generative AI’s breakout year, but that has been greeted by some fairly mixed responses, particularly from Designers. As the terrain we all live on reconfigures around the new technology, the role of the Designer needs to adapt. It’s likely the role as we know it today will have very different requirements in the future. The natural reaction, without clear alternative has left Designers asking, per Design Week, Is AI an ally or a threat to creative industries?

Recently, Jakob Nielsen has claimed that the ‘AI-driven UX boom’ has become an ‘evolutionary certainty.’ Such commentary, from a widely recognised expert of the field, is a sure signal of the need to change. There’s a growing number of voices like Nielsen’s discussing the intersection between AI and the UX Designer. Jakob Nielsen, continued:

“Any day you do old-school UX work with no AI support is one more stone in the coffin to degrade your career prospects in two years when AI experience will be mandatory as the tools improve. Nielsen’s Second Law of AI: You won’t lose your job to AI, but to someone who uses AI better than you do.” (Jakob Nielsen, Substack 18th September 2023.)

This narrative juxtaposes what’s historically been referred to as the Extended Designer (one who leverages AI) against the Non-extended Designer. Further, Nielsen and Moran have described how to get started with AI in the UX Designer’s workflow, and how the “UX field needs to urgently engage with AI. This is partly because usability improvements are sorely needed for current AI tools but just as much because UX work can be vastly improved through the appropriate use of AI.”

In this article, I argue that the modern Designer must transition into the Extended Designer. The concept is not new, but surprisingly, very few articles seem to reference this 60 year old (at least) concept. My goal is to reintroduce this identity, and to help this idea ‘click’, to encourage you to get involved. The basis of the argument is not about what will change, but about the things that will never change.

In that context, AI is very much an ally, but there is a need to reassess the role of a Designer, both pragmatically and philosophically. My intention here is to begin to address that narrative, and to awaken the potential of AI-assisted creativity within the modern UX Designer. I will do so by pointing back to a time when these techniques were being explored with optimism, and without any hints of ‘taking over jobs’ or similar anxiety-inducing language. My aim is to inspire you to approach the toolset with a sense of opportunity and potential, to level-up their own abilities, and to reframe the purpose of the Designer as ‘handicrafts’, and more as ‘governor’. The role of the Human is to be the judge of the work, and to steer toward desirable outcomes. We move higher up the chain to something irreplaceable. Something an AI can never replace: what it’s like to be human, and to provide a means for any human to create value (albeit maximised gains, or minimised costs, in many domains) to other humans.

Amplifying impact

To truly understand what AI can provide the Designer, we need to flip the current narrative from one of loss, to one of gain.

For the majority of Designers I’ve had the privilege to work with, I’ve been told they seek ‘excellence’. When asked why this extrinsic goal matters, they wish to be recognised by peers, valued for their contributions, and even more so: to have impact on the world. ‘To make a dent on the world’, as Steve Jobs described his own aim. As Herbert Simon stated, to change existing circumstances into more preferred ones. To have been such a meaningful fulcrum, that the legacy is echoed for generations.

Does this sound familiar?

Consider whether this also sounds familiar (using the classic Double-Diamond, and leaving the issues with that to one side):

- Discover:

— In order to create the best thing, we must first go deep into inquiry to understand what ‘best’ means — who’s the judge?

— In order to go deep into inquiry, we must spend time understanding customers and surfacing contextual insights, which takes time and effort, and sometimes is not recognised by other peers in a business

2. Define:

— Once we have data, we must make sense of it — which also takes time, and not always

— Next, we must articulate, or ‘define’ the problems,

— Finally, we prioritise the most important problems

3. Design:

— We have no way of knowing ahead of creating a solution which one is the best, and must subsequently test, and validate

— We create a range of alternative approaches, then test each in turn to see the results

4. Deliver:

— We come up with the best, and we test and learn to continue optimising

— If we did it right, our product/deliverable facilitates desirable outcomes for the intended user/audience.

Although Designers say their aim is ‘impact’, they spend a disproportionate amount of their time engaged in what might be termed ‘sausage-making’. They spend weeks, months, years even with heads down, looking at the road.

A good designer will focus on the details, knowing that the details are the design. For this reason, the designer is to the product what the magnet is to metal: an ordering and alignment function. It takes the best, most applicable choices to aggregate into (theoretically) a great product. The product is therefore the compound effect of all those decisions at every level, both seen and unseen.

For this reason, I believe the Design function is the lever to the entire production process. It defines the value the entire system is ordered at producing. Not only that, it is the lever to creating difference for the customer. Maximising the degree of benefit for the customer is the most fundamental, but most often overlooked measure of effectiveness.

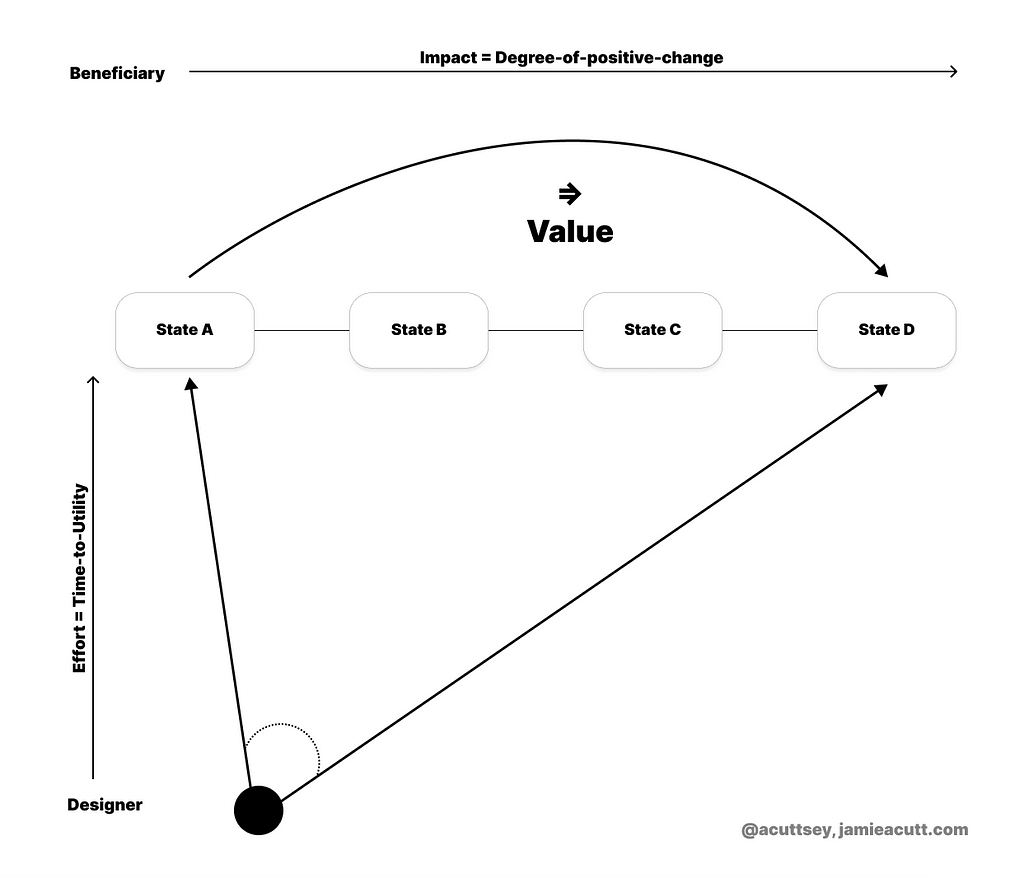

Therefore Time-to-Impact is, or should be, the Designer’s real goal.

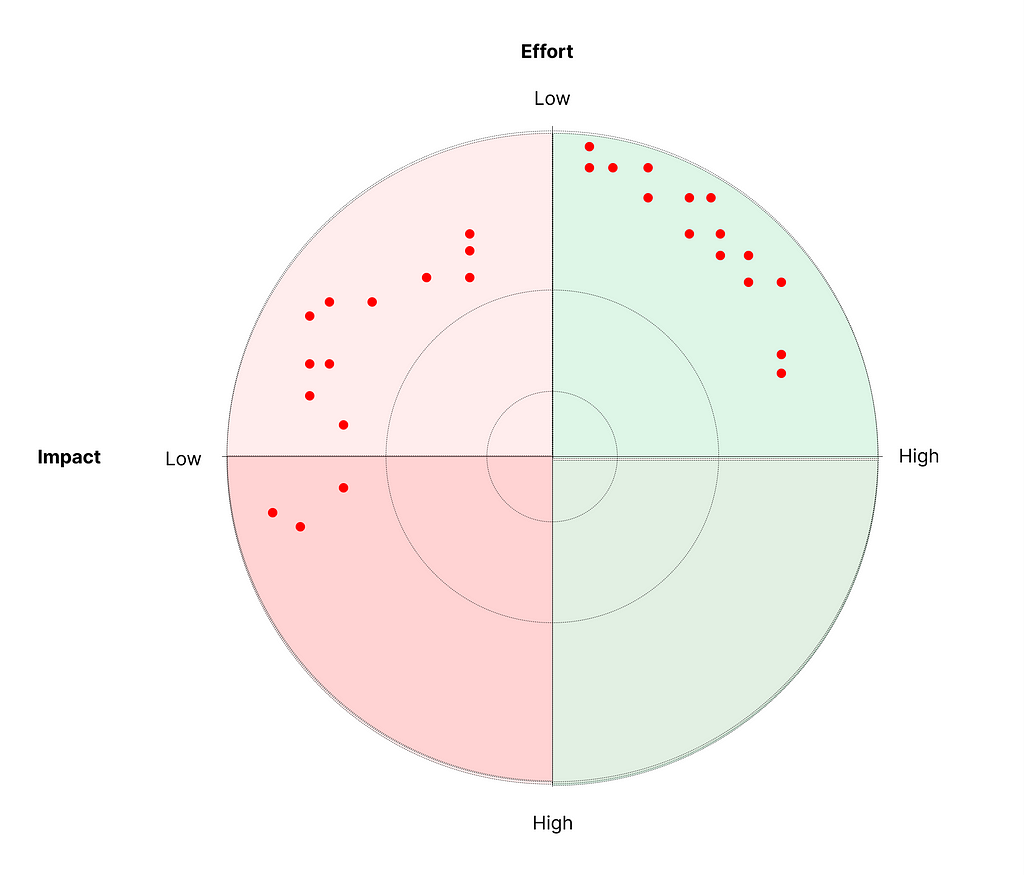

And there are constraints in this process. As the course is charted to the perfect product, there are business assumptions being made. For example, that senior leaders are the best judges of the value the organisation can produce for customers. And then in the invention process, there are constraints on how many visions of the future, or a new status quo the designer can invent. How many versions/options of a design will you create? The likelihood is, you’ll create between 3–6 variants. Maybe explore up to 10x more, for the sake of ruling them out of viability. Ultimately, these are a few alternative routes to solving a defined problem statement. Functional fixation, something we can train ourselves to overcome, is always present. It’s possible for novel ideas to be discovered when one doesn’t fall back on well-trodden paths. AI can open up the variety to the range of all possible combinations. Hundreds of thousands of more variations.

So what AI represents is a means to lower the effort, increase the variety of ideas, and maximise impact, whilst shortening the time to deliver. Shortening the time for you to make a dent in the world. Instead of looking down at the work, we can look up and out.

The only problem is, the tools to truly do this don’t exist yet.

We need a Design Machine.

The Birth of the Design Machine

The 1950s-1970s were decades of incredible optimism. Moon landings, represented both the achievement of human Will and ingenuity — and observers were in awe of the future. Science-fiction narratives exploded, and David Bowie captured the essence of the marvellous and the perilous in Space Oddity. It was a period in which the potential for technology to liberate humanity was very much being imagined. Theorists were beginning to tackle the pros and cons, the benefits, and the dangers of these technologies.

Writing in 1969, Nicholas Negroponte opened his work with a disclaimer, “Most of the machines I will be discussing do not exist at this time” (Preface, May 1969). Writing almost like the Nostradamus of Design technology, in Architecture Machines (1970, MIT Press), Negroponte hypothesised that AI would impact 4 key areas for Designers:

- Automate processes

- Designers collaborating with artificial intelligence

- Designers moving from a production to a governance role

- Designers will spend less time making products, and more time making progress

The book also predicted the following events, which have come to fruition over the last 30 years, as the technologies diffused into society, and became commoditised:

- AI beating Chess Masters

- Computers in every home

- The prevalence of touch screen devices

- The transformative power of the internet

And even more, Negroponte made predictions about the future role of Designers in collaboration with AI Designers: The birth of The Extended Designer.

Written at a time when all of these ideas were exploring the potential future of technology, we are now living in a time when the potential of The Extended Designer is now becoming a reality.

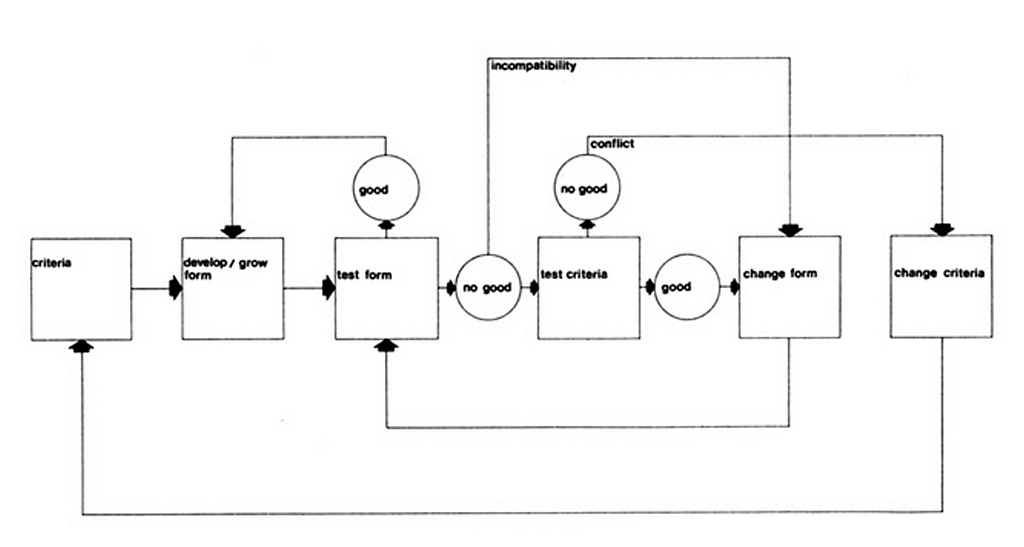

Negroponte outlined that, with AI, “…the design process is an evolution of (1) the product, the form; (2) the process, the algorithms; (3) the criteria, the information.” He further explained how “….the concurrence of “extended designer” and “artificial designer” will force a design redundancy and an overlapping of tasks that are necessary for the understanding of intricate design couplings.” (p25–26). Far from making the designer redundant, it would provide potential for empowerment, and improved efficiency. Negroponte continued:

“Such a colleague would not be an omen of professional retirement but rather a tickler of the architect’s imagination, presenting alternatives of form possibly not visualized or not visualizable by the human designer.” (p39).

Going back to the 3 pieces, it could extend and enhance ‘the product, the form’, whilst reducing the effort and cost of the process, by improving ‘the criteria, the information’.

But what would such a machine actually look like, and how might we interact with it? To answer this question, we must consider what the requirements for what such a device might be.

Blueprints for a Design Machine

In order to design a Design Machine, we must first ask what makes a good designer? What would they need to know, how might they interact, and what degrees of challenge, intervention and reinforcement are needed during the decision-making process? Whether the collaborator were human or a machine, doesn’t matter. In this section, I shall describe the 6 key areas for the Design Machine to augment the work of the human designer.

One key challenge that AI can dissolve from the designer’s workflow is processing data needed to make a good decision. Numerous times in my career, I’ve spent long periods of time manipulating data. When I’ve had the time. And perhaps spent too long. Collecting, Cleaning, Aligning, Comparing. This process was described by Licklider (1960), in an article about Man-Machine Symbiosis. After inspecting his own workflow, Licklider observed “It soon became apparent that the main thing I did was to keep records…” similar to what I’ve observed from my own workflow. See whether this sounds familiar:

“About 85 per cent of my “thinking” time was spent getting into a position to think, to make a decision, to learn something I needed to know. Much more time went into finding or obtaining information than into digesting it. Hours went into the plotting of graphs, and other hours into instructing an assistant how to plot. When the graphs were finished, the relations were obvious at once, but the plotting had to be done in order to make them so. At one point, it was necessary to compare six experimental determinations of a function relating speech-intelligibility to speech-to-noise ratio. No two experimenters had used the same definition or measure of speech-to-noise ratio. Several hours of calculating were required to get the data into comparable form. When they were in comparable form, it took only a few seconds to determine what I needed to know.”

This process should feel familiar to most people working in Design, or Research. Even the process of desktop research, for example (understanding competitors, doing walkthroughs of competitor experiences, understanding the positioning of the business compared to competitors) takes a disproportionate amount of time. But often this type of work needs to be done, because we have to put the pieces of the puzzle on the table before we can construct the picture. The manipulation of data has always been needed in order to make a good decision, but the majority of the ‘effort’ resided in the manipulation of the data, not in the time to make a decision. Licklider continued:

“…in short, my “thinking” time was devoted mainly to activities that were essentially clerical or mechanical: searching, calculating, plotting, transforming, determining the logical or dynamic consequences of a set of assumptions or hypotheses, preparing the way for a decision or an insight. Moreover, my choices of what to attempt and what not to attempt were determined to an embarrassingly great extent by considerations of clerical feasibility, not intellectual capability.”

In effect, the ability to make good decisions and to think clearly was derived from the time invested in creating artefacts that assisted understanding. Something we see often in the majority of the processes within the Double-Diamond, and often in the processes used by Product Managers to make good value-based judgements. The only option is to have Good Data, and Good Reasoning, because as Berkeley observed, all other options create poor results: “Poor data and good reasoning give poor results. Good data and poor reasoning give poor results, poor data and poor reasoning give rotten results” (Edmund Berkeley, 1967).” (via Negroponte, p53)

And the problem is ever greater, since as Beer observed, complexity grows as interrelationships grow. And as interrelationships grow, so too do the “…diverse variables and …. unforeseen and continually changing sequences” that must be calculated. In other words, by the time the human has manipulated this data, the environment may have already changed. I call this ‘reality drift’. To overcome this “severe problem”, Licklider acknowledged that “Computing machines can do readily, well, and rapidly many things that are difficult or impossible for man, and men can do readily and well, though not rapidly, many things that are difficult or impossible for computers.”, and that through Man-Machine Symbiosis, “it seems evident that … cooperative interaction would greatly improve the thinking process”.

Indeed, all of the manual manipulation Designers and Researchers undertake to make decisions might easily be automated, so as to provide clearer thinking, and a faster time-to-impact ratio. Taking this example, Negroponte described the Man-Machine Symbiosis “… as the intimate association of two dissimilar species (man and machine), two dissimilar processes (design and computation), and two intelligent systems (the architect and the architecture machine). By virtue of ascribing intelligence to an artefact or the artificial, the partnership is not one of master and slave but rather of two associates that have a potential and a desire for self improvement.”

Dissecting the specification for the AI-aided Designer, we might propose that an Adaptive Design Machine would (with the help of Negroponte’s original wordcraft) operate on 6 key areas:

- Collect knowledge and understand:

— To maximise the fit, or duet, between designer and machine:

2. Personalise communication with Designer:

— Such a machine, “…after observing your behaviour, could build a predictive model of your conversational performance. Such a machine could then reinforce the dialogue by using the predictive model to respond to you in a manner that is in rhythm with your personal behaviour and conversational idiosyncrasies.” (p13) “The dialogue would be so intimate — even exclusive — that only mutual persuasion and compromise would bring about ideas, ideas unrealizable by either conversant alone.”

- “Through familiarity with a specific designer’s idiosyncrasies, the appropriateness of the machine’s interruptions would be suitably reinforced by context — the inception of an intelligent act.” (p25)

- Synthesise in a Designerly model, “design information is retrieved by geometric (topical) search rather than by intersecting generalities.” (p53).

- Improvise: Emulate the best human partners. Provide input to choices in real-time. Provide challenge to ideas in real-time. Build on top of ideas in real time. Expand ideas in real-time

- Adopt a designerly persona or personalities, such as Dieter Rams, in order to determine creative decisions and constrain outcomes toward known artefacts.

3. Look outwards, and sideways: To counter the risk of becoming an echo-chamber

— Experience the world directly (not just through the interaction with a Designer). “By sampling its environment, an adaptable machine could freely move from a state of universality to a state of single- mindedness.” (p27)

— Observe a range of designers, allowing for ‘…objective scrutiny that would consist of (1) an evolutionary mapping of popular desires, (2) a statistical overlay of solution patterns, and (3) the images of architects he esteems.” (p29).

— Become a cross-functional collaborator: an AI can emulate personas, when asked to act as a Programmer, Marketer etc.

4. Look upwards and outwards: Generate high-variety solutions to high-variety problems (p39):

— Morphological analysis: Define the variables and conditions, as well as their mathematical combinations in order to expand the range to the fullest potential.

— Compensate for constraints both in the problem and the solution to optimise fit: one accommodates under-constrained problems; the other works within over-constrained situations.

5. Automate process:

— “A process is a progressive course, a series of procedures. A procedure is replicable (if you understand it) in an algorithm; its parts have a chronological cause-and-effect relationship that can be anticipated. A procedure can be replicated with the appropriate combination of commands. In short, a procedure is deterministic and can be computerised within a given context.” (p59).

— Learn from previous processes to optimise an algorithm. Self-inspect courses to optimise paths to the outcome.

6. Simulate events, and predict probable outcomes before physical implementation or deeper investment (p47).

— Look ahead to how choices now will impact circumstances later, in real-time. Based upon actual and projected/predicted metrics.

— Suggest course corrections both forward-chained and backward-chained to the human in order to further improve outcomes.

In this specification, the Human acts as the bridge to the context and the problem, understanding both and how a solution can best fit it. Only the human can determine whether the solution works or needs ‘another turn of the wheel’. The Machine acts as the bridge to broader context, and a bridge to the subject matter. It loops in the broadest range of options, and mitigates the human’s natural liability to narrow options. Therefore there are 3 relationships: the one between the human and the problem space, the one between the machine and the subject matter, and importantly for the usability of the tool, the one between the Human and the Machine. The personality of each effectively become interfaces. The collaboration is the process. What they create together is the product.

In effect, it’s a full acceptance that both sides need each other in order to be successful. This is the true definition of symbiosis:

“living together in intimate association, or even close union, of two dissimilar organisms”.

To further highlight an important aspect of the Design Machine, let’s take a look at how it accommodates constraints. As Negroponte explained:

“The under constrained situation… has a large set of possible solutions. The criteria are satisfied by many alternatives. These alternatives must then be evaluated by the architect using “intuitive” means, selection criteria he either does not understand or has never presented to the machine.

In the over constrained problem, the generating mechanism is presented with great amounts of factional criteria that no form can completely satisfy. The generating mechanism searches for a solution that best relaxes the constraints, a point of greatest “happiness” and least “friction.” The resulting form is a status of criteria compromise where the constraints least antagonise one another.” (p39).

In which case the Design Machine learns and adapts its choices alongside the Human Designer to continue to find solutions that find the “a point of greatest ‘happiness’ and least ‘friction’”. This is ultimately the target of most design effort.

Designer as a Pilot

Channelling the view of McLuhan, Negroponte cited that the ‘how’ of doing the work, or the medium, had almost entirely overtaken the message, or purpose of design. “In the past few years, however, it has so dramatically overstated itself that the “message” has indeed become dominated by the “medium.”” (p17). We now see this problem in our obsessions around mediums, and around tooling. What Artiom Dashinsky has recently referred to as ‘Figmaism’ (Sept 2023). But the role of the Designer has never truly been about the act of making, but about the difference produced, i.e. the impact. The making was a necessary component to get to the impact. Or as Aristotle once stated, the purpose is ‘not the outward appearance, but the inward significance (essence, Latin: esse: ‘being’).’

Charles Eames once claimed that ‘it’s the designer’s role to determine whether something should exist’. This is the vital task of the designer. And yet, designers have so embedded (‘entrenched’ perhaps) their identity with the act of making, that they have at the same time abandoned this vital identity as the judges of quality, and of determining the value of what Design manifests.

Thinking along these lines, and predicting the incredible shift in identity that would happen because of the industrialisation of Intelligent Machines (i.e. AI in the workplace), the Cybernetician Stafford Beer drew a distinction between Homo Faber (Mankind the Maker), and Homo Gubernator (Mankind the Pilot). Since ancient Greece, the identity of the human has been in creating, making, building, constructing. But the purpose of these things was never the act of making in-itself, but as a means of living better. In Cybernetics, the process to create something is called ‘Allopoeisis’ (‘other-organisation’, or the system used to create something other than itself), or in our current example, the work, structure, process a team uses in order to produce a product). Product and Process are separate, but interdependent, concerns.

And this summarises the argument I’ve presented here. We’ve spent so long in the act of building ships, that we forgot that the point of the ship is to get you across the water. As Chuang T’su once claimed, the rabbit-trap exists to catch the rabbit, not for the sake of having the trap. Or as Bruce Lee also said, the solution is a boat to get you across, but not to carry on your back once you reach the other side. We’ve reached the other side.

And this, my friends, is the case for the Extended Designer and the Design Machine.

Inventing a Design Machine

As we’ve seen, it was Negroponte who proposed the concept of an Architecture Machine, a tool to be used by the Architect to make the best possible decisions, and make the greatest buildings mankind has ever been able to create. Beyond what it had been previously possible to even imagine! As Pangaro and Dubberly stated more recently, eventually “the original idea of the architecture machine was set aside and remains unrealized.” (2019, 7). Even tools that have changed the game for Architects and Industrial Designers such as AutoCAD have not achieved such a lofty aim.

And that is the call-to-action for modern Designers. We have a latent opportunity, right now, to pick up these examples, and to not just imagine a duet between Extended Designer and Artificial Designer, to create ever greater pioneering work — work that transcends the narrow biases and capabilities of the human mind, and the time it takes to make. We can make it happen now.

This was the vision that Negroponte described all the way back in 1969, with complete but objective optimism, without the existential fear of redundancy. This is the opportunity, our opportunity, and it’s happening right now. Jump in the driving seat, and explore how being an extended designer could potentially 100x your impact.

Postscript / Risks of a Design Machine

It’s important to comment for balance that AI-assisted Design practice is not all up-side. Quite obvious risks exist within a senior where a Designer-of-one relies on the input and output of an Artificial Designer. It is necessary to imagine a world in which all designers use AI, and to ask, what are the downsides of that state? Some top-level thoughts include:

- The likelihood of a designer to feel that human collaboration is not as valuable, and therefore deprioritised. The outcome is less collaboration with peers.

- A rise in the Dunning-Kruger effect of feeling competent in fields that one has no capability of recognising whether something the AI says is consistent with experts in that field. For example, asking an AI to be a Marketer, or Data Scientist and then providing advice that conflicts with a human expert. At least there would be a difficulty to tell when this might be the case.

- Unintended consequences of considering the digital data the AI has represents all the data needed to make decisions.

- Wider socioeconomic side effects of fewer designers needed.

- Impact to future training and education programs, restructuring to become more reliant on tools. And a degree of incapability exposed when the tool is unavailable.

- The difference between a personal tool and a public tool. A personal tool will be trained in specifics based upon interactions between Designer and AI. This could lead to echo-chamber effects.

- Ownership of the AI is ultimately in the hands of the inventors and owners, and at their discretion changes are or are not made. Investments would be made towards outcomes desirable to the company first as survival and viability are more important than utility.

Some of these ideas are only hypothetical, but are capable of changing the Designer’s relationship with the field of Design, with other designers, other stakeholders, the customer, with their product, and the world.

References and Further reading

Ashby, W. R. (1956); An introduction to cybernetics. New York: Wiley.

Dubberly, H., & Pangaro, P. (2007); ‘Cybernetics and Service-Craft: Language for Behavior- Focused Design’, in Kybernetes, Volume 36 Nos. 9/10. Available online.

Dubberly, H. & Pangaro, P. (2015); ‘How cybernetics connects computing, counterculture, and design’. In Hippie modernism: The struggle for utopia (pp. 126–141). Minneapolis, MN: Walker Art Center.

Dubberly, D; Pangaro, P (2019); Cybernetics and Design: Conversations for Action, in Design Cybernetics: Navigating the New — 2019 — Thomas Fisher and Christiane M. Herr, Editors — Springer.

Glanville, R. (2003); ‘Second-Order Cybernetics’. In Parra-Luna F. (Ed.) Systems Science and Cybernetics, Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems, developed under the Auspices of the UNESCO. EoLSS Publishers, Oxford: electronic. Available online via Pangaro.com.

Licklider, J. C. R. (1960); ‘Man-Computer Symbiosis’, in IRE Transactions on Human Factors in Electronics, volume HFE-1, pages 4–11, March 1960.

Schön, D. (1983); The reflective practitioner. NewYork: Basic Books.

Simon, H. (1969); The sciences of the artificial. Cambridge, MA:The MIT Press.

von Foerster, H., et al., (Eds.). (1950–1957); Cybernetics: Circular causal and feedback mechanisms in biological and social systems: Conference transactions. NewYork: Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation.

von Foerster, H. (1984); ‘Disorder/order: Discovery or invention?’ In P. Livingston (Ed.), Disorder and order: Proceedings of the Stanford Interaction Symposium (pp. 177–189). Saratoga, CA: Anima Libri. (Reprinted in von Foerster, H. (2003). Understanding understanding: Essays on cybernetics and cognition (pp. 287–304). New York: Springer.

von Glasersfeld, E. (1987); ‘An introduction to radical constructivism’. In The construction of knowledge (Chapter 10; pp. 194–219). Salinas, CA: Intersystems Publications.

von Glasersfeld, E. (1995); ‘Radical constructivism: A way of knowing and learning.’ Studies in Mathematics Education Series: 6. London: Falmer Press.

https://uxplanet.org/the-impact-of-ai-on-ux-design-opportunities-and-challenges-a9e466d319ad

The extended designer, and the design machine was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.