For more than 100 years, IBM has been one of the prominent names among computing giants, dominating the early global market with technical and service superiority. They forged a path of innovation leading to Nobel Prizes, lucrative defense contracts, and they even helped to put a man on the moon.

However, IBM’s success was also the result of a progressive corporate culture well ahead of its time, implemented by Thomas J. Watson, Jr. when he took the helm of IBM from his father in 1952, and grew IBM on the premise that “good design is good business.”

The Origins of IBM Design //

In the early 1950s, Thomas J. Watson Jr. took a walk down Fifth Avenue in New York that would change the future of IBM forever.

The Olivetti shop caught his eye, where he quickly noticed passersby engaging with the typewriters setup on the sidewalk, and he too found himself admiring the contemporary designs and the assortment of colors sparkling in the sun.

He peered inside and marveled at the brightness and modern aesthetic of their showroom. It felt alive and fresh! Stepping back, he thought of how IBM’s computers were bland and boxy sitting in a dark showroom. He realized that IBM’s dull experience was a metaphor for their brand, products, and company. He decided right there that “I could put my stamp on IBM through modern design.”

Watson Jr. discovered that the power of design — much like love — is a universal language easily understood by anyone without words or sounds, and yet it has the power to spark our emotions, communicate vast amounts of information, and solve the world’s toughest problems.

We try to convince ourselves that we are rational beings, who make choices based on logic. In truth, we are highly emotional creatures. And that fateful walk down 5th Avenue sparked a powerful emotional response from one of the preeminent CEOs of the early 20th century to the world of design.

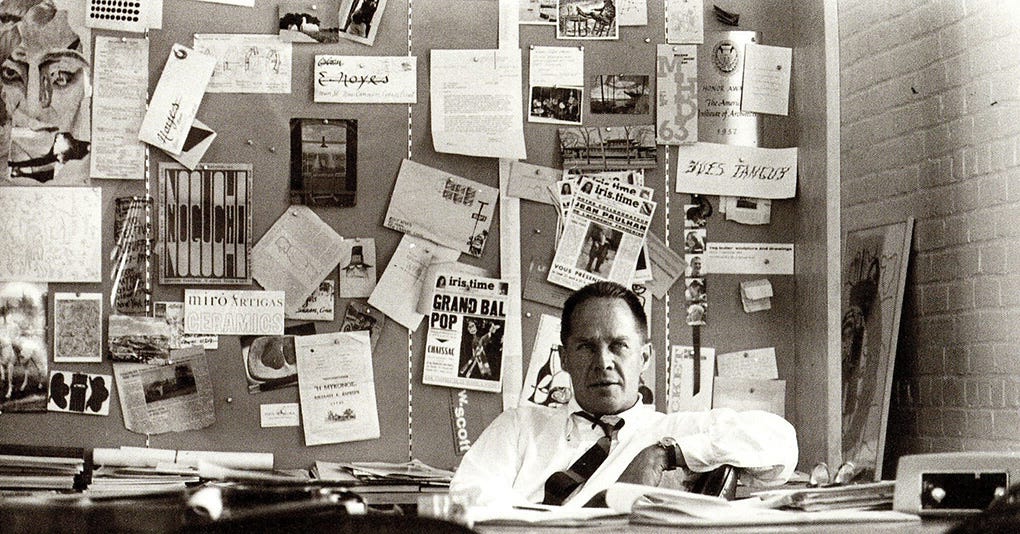

The Design Genius of Eliot Noyes //

Thomas J. Watson Jr.’s first major step towards his goal of reinventing IBM with a design focus was to hire Eliot Noyes as the company’s first design consultant. He was a well-respected architect and industrial designer with a distinguished career, including his work as curator of industrial design at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Most importantly, Noyes was fully capable of bringing Watson Jr.’s new vision for IBM to life.

Noyes was known for combining traditional techniques and high modernism to design his architectural aesthetic. Much of his design philosophy was influenced by Peter Behrens, a prominent member of Werkbund and pioneer of corporate design. Behrens’ ideologies were passed on to Noyes through his professor, Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus school and proponent of modern and industrial design. Noyes conceived the idea of “organic design,” which can be interpreted as the link between the characteristic of being organic and the harmonious organization of different parts.

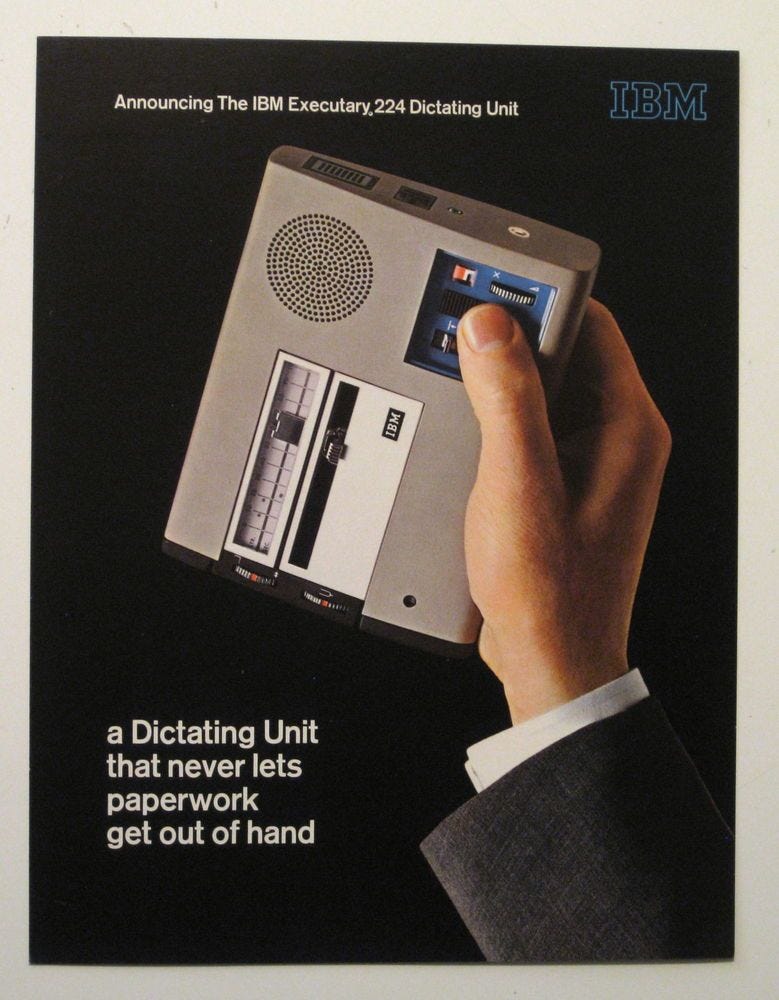

At IBM, Noyes set out to create a completely original corporate design program that encompassed all aspects of the company. His goal was monumental and transformative for both IBM and the growing field of design, where it ushered in a new era in which a business organization — its management, operations and culture, as well as its products and marketing — was designed as an intentionally created product of the imagination.

Noyes famously wrote “in a sense, a corporation should be like a good painting; everything visible should contribute to the correct total statement; nothing visible should detract.” This painting would embody something specific and immediately recognizable, yet never uniform or static.

Beyond his original design philosophy, one of Noyes’s best qualities was his ability to recruit exceptionally talented artists, designers and architects, including some of the best creative minds of the day, including Charles and Ray Eames, Eero Saarinen, Paul Rand and Isamu Noguchi. They each created a massive range of creative expressions, equally contributing to IBM’s brand evolution, while grounded in Noyes’s design philosophy.

Noyes described his own role as a “curator of corporate character.” He explained, “It does seem to be a part of the role of the designer to help identify this character, and then express it in terms of the most meaningful goals and the highest ideas of the company and in the broadest context of our society and economy.”

“The impact Noyes had was incredible,” says Steven Heller, author and longtime design director at the New York Times. “He oversaw the modernization of all aspects of the brand. IBM became the company to beat, the paradigm of the modern corporation.”

Noyes expertly guided Saarinen in his design of the company’s Thomas J. Watson Research Center in Yorktown Heights, New York, a long curve of glass and stone that gives researchers inspiring views of the countryside while providing unique spaces for them to engage and collaborate with one another.

Designed by Eero Saarinen, 1961

He also worked with his protege — and future design legend — Paul Rand to help evolve the IBM brand, which culminated in 1972 with a series of logo designs that led to the famous version formed from stacked stripes. The “8-bar” logo symbolized speed and dynamism, which made the company’s initials instantly recognizable worldwide, and is still in use today.

Noyes not only managed this extraordinary team of designers, but he was also a prolific designer himself, responsible for designing the iconic IBM Selectric typewriter and the Management Development Center in Armonk, New York.

Design @ IBM Today //

The extraordinary impact of Watson Jr.’s radical decision to lead with design, as well as the legacy of Noyes and his design team still resonates almost 70 years later, where IBM Design was formed in 2012 to further expand design as a service to hundreds of corporate clients around the world.

What we borrow from our own design history is not a mid-century aesthetic in stylistic terms, but the modernist attitudes and approach used at the time.

Eliot Noyes taught us that brand is character, and should be built through curation. Paul Rand taught us the importance of endless experimentation. Charles and Ray Eames brought out our playful nature, and were pioneers of what is now referred to as “branded content” and “experiential.”

Their methods are as modern today as ever before — maybe more so.

– IBM Design

Almost overnight they achieved international recognition for their innovative design services, embracing their rich tradition of design in the process.

The secret to their success is how they continued to utilize Noyes’s approaches of leading with design, empathy, and experimentation; which we now commonly refer to as design thinking. And then they amplify it by combining design thinking with more modern approaches — like Agile and DevOps — to help clients design for the future while evolving their existing businesses.

Design Philosophy:

IBMers believe in progress — that by applying intelligence, reason and science we can improve business, society and the human condition.

Given our scale and scope, good design is not just a requirement, it’s a deeper responsibility to the people we serve and the relationships we build.

The thing that stands out most to me about their Design Philosophy is in how ethereal it is, and how little traditional design is even mentioned, aside from the word “design.” They’ve committed themselves to serving others and building relationships, where they’ve placed human purpose at the heart of their philosophy. It’s their raison d’etre.

And it’s very Noyes-esque.

This purpose guides every IBM designer and everything they design, thoughtfully provoking and iterating towards progress. Leading people and clients to new thinking, and ultimately, new outcomes. All by design.

Conclusion //

Thomas J. Watson, Jr. was one of the first executives of the modern era to embrace design in many aspects of business, from culture to branding to products & services. This forever changed the landscape of corporate America by serving as a new paradigm for success while inspiring the next generation of leaders like Steve Jobs, Tim Brown, and countless others.

Corporations now view design as a critical component to express their brands and their values — from Apple’s products, to Starbucks’ in-store experience, to Disney’s entertainment venues. Additionally, companies have also employed the principles of design thinking, which can be partially attributed to Noyes and his team of designers utilizing design as a solution to solve many multi-faceted problems within the halls of IBM.

Expanding on the successful use of design thinking, Billy Seabrook (VP, Global Chief Design Officer at IBM) discussed design thinking wins with other design leaders at the Fortune Brainstorm Design conference earlier this year. Seabrook identified the characteristics of a leading design-oriented organization, which represents one-third of those recently surveyed by IBM. “We discovered a cohort that really embraces design across the entire organization, both for how the company operates and how they go to market,” Seabrook said, adding that those companies saw over 50% higher revenue growth in the first half of 2021. IBM identified those companies as the “Design Vanguard” because they share three commonalities in their approach:

- Emphasis on user research

- Investments in workplace tech

- Developing new solutions at scale

Despite this connection to financial success, many executives still see design as a craft that is specific to one domain, IBM’s research says. In fact, 61% of executives surveyed said design talent was a “nice to have” as opposed to a necessity.

Thomas J. Watson, Jr. was inspired to pioneer the strategy that “good design is good business” at IBM with a simple stroll down 5th Avenue. But his work with Noyes at IBM was only the beginning for design. We need to find creative and unique ways to inspire more leaders to embrace and deploy design broadly so that we can utilize the exponential power of design in corporate America to solve the world’s biggest problems.

How IBM revolutionized corporate America with design was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.