How our perceptions of the world around us and the groups we work in may be misleading

This week builds on our previous post on cognitive illusions and perception errors. optical illusions help illustrate how blind we are to the cognitive heuristics we use to make sense of the world around us.

What they show is that so much of our perception is constructed by what our brains ‘expect’, not an objective representation of reality.

We intake relatively little information about our environment and ‘fill in’ the rest.

There’s no shortage of examples when it comes to our visual perception. We shared a few examples last week and many of these other studies are likely familiar:

- How we interpret motion can be influenced by others as we adopt group norms.

- The rubber hand experiment shows we can trick our brains into feeling pain through visual association.

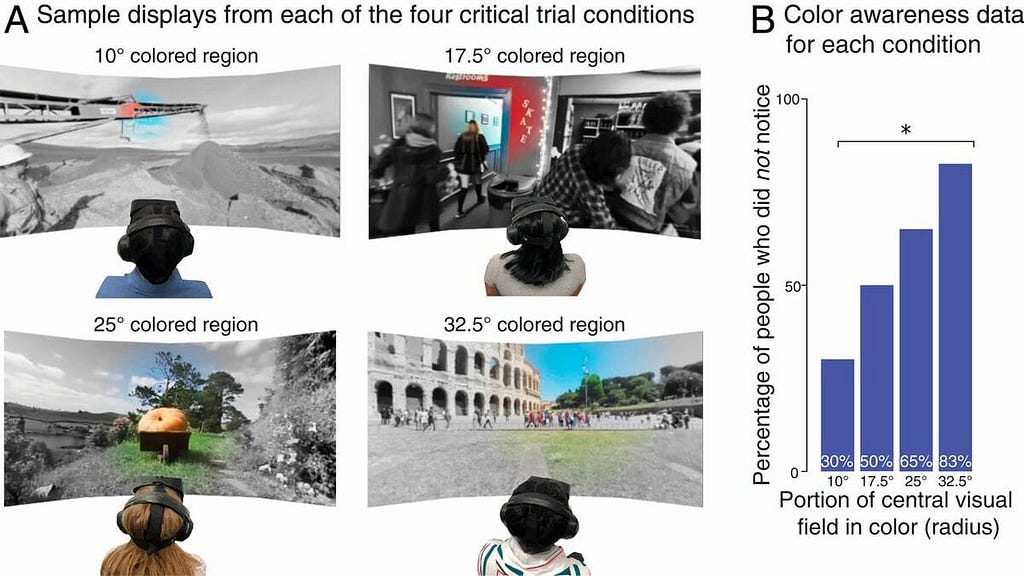

- Much of our peripheral vision is constructed and up to 2/3 of color in our field of vision is assumed. (see below)

We don’t experience objective reality, we experience an interpretation built on relatively little information and reference points — that can be influenced by external factors

The parallel here is that these same patterns are observed for cognitive illusions — errors we often don’t realize when processing information or making judgments. The problem is that we can recognize these visual illusions (and be amused and entertained by them), but it’s difficult to really grasp the idea that much of our reasoning is constructed on-demand and based on heuristics we’re programmed with or built over long periods of time.

“All you’ve got to go on is streams of electrical impulses which are only indirectly related to things in the world, whatever they may be.

So perception — figuring out what’s there — has to be a process of informed guesswork in which the brain combines these sensory signals with its prior expectations or beliefs about the way the world is to form its best guess of what caused those signals.”

– Anil Seth, Cognitive Neuroscientist — source

It’s neither energy efficient nor necessary in most situations for our brains to calculate complete answers based on perfect information, so we opt for cognitive shortcuts.

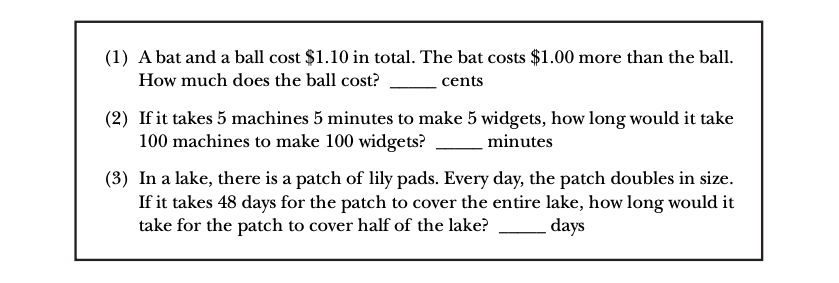

A simple, non-visual example of this is the ball and the bat problem or any of the cognitive reflection test questions.

In the first question, most participants, regardless of education or intelligence, produce the incorrect answer of 10 cents.

When forced to work out the problem, or when primed with techniques to slow down and trigger system 2 thinking, many arrive at the correct answer, 5 cents.

This is an impulsive substitution error — our instinct is to opt for simpler problems over more complex ones.

Similarly, we look for social cues to adopt our beliefs or construct them in real time as we’re working in groups. (see information cascades and groupthink). We’re subconscious imitation machines, constantly molding to our environment.

We might think of this as good or bad news. Bad news because these mechanisms can lead toward a regression to the mean of the group and conformity in thought.

Or good news because these are the mechanisms that motivate large groups to coordinate and align teams to common goals.

We can make the argument that explicit and observable beliefs, incentives, and principles can combat the spread of dangerous implicit perceptions that drive these collective illusions — before they become real.

“Making things more observable makes them easier to imitate, which makes them more likely to become popular.” — Contagious, Jonah Berger

What are collective illusions?

These challenges with individual decision making are typically observed in scenarios where the answer is clear or outcomes are known. Conversely, with strategic decision making the environment is uncertain and information is incomplete.

More often than not, we’re working in groups, dealing with ‘politics’, and triggering highly emotional responses. These are meaningful factors in how we make and communicate decisions.

“The real world provides only scarce information, the real world forces us to rush when gathering and processing information, and the real world does not cut itself up into variables whose errors are conveniently independently normally distributed, as many optimal models assume.”

— Gerd Gigerenzer, How Good Are Fast and Frugal Heuristics?

This is where large group dynamics, particularly around shared beliefs (or the perception of shared beliefs) might help explain these challenges beyond the effects of groupthink in a conference room brainstorming session.

We rely on cues. In the case of social norms, we combine our existing beliefs and assumptions with real-time observations to understand how to act or respond. Without these unwritten rules, there would be social chaos. People would cut lines, face each other in elevators, and let a sneeze go without a proper ‘bless you’. (shock and awe)

But there’s one cue that’s particularly interesting — our desire to conform compounded by our tendency to miscalculate the beliefs of others.

Todd Rose writes about this from the broader perspective of cultural phenomena in his book, ‘Collective Illusions’, but the research (and the macro point of view) is applicable to how organizations operate.

In short, we have a difficult time accurately perceiving the beliefs and motivations of others, yet we conform to our perception of the presiding norms. This systemic, self-reinforcing effect can eventually convert these false perceptions into reality.

If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences — The Thomas Theorem

To summarize a few of the arguments:

- Studies, like this one on the use of malaria nets, show how individuals act in accordance with beliefs they perceive are shared by others, but that perception is often miscalculated

- Collective illusions can quickly become reality as the perceived norms become the real norms, overtaking what was previously the beliefs of the silent majority. (e.g. it only takes 5–10% of the comments on a social media post to account for a perceived majority of opinion)

- Nonconformity triggers cognitive errors that are similar to how we react in disgust. When our group agrees, we get a dopamine hit (neural reward), when someone strays from the presiding point of view, we get a neural error.

So what might we glean from this tendency to fabricate and fuel these collective illusions?

We can assume the same tendencies exist in organizations.

The beliefs and assumptions that drive decision making are based on our perceived beliefs in others — and those perceptions may be inaccurate. Most companies were built on strong convictions that guided their decision making and turned out to be right — or died because they held on to their convictions too long.

“Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly, one by one.” — Charles Mackay

The risk is that these collective illusions within a culture (especially where productive discord isn’t welcomed) can quickly create an autoimmune response to contrarian viewpoints — which is difficult to recover from.

Consensus, or the illusion of consensus, is comfortable. Conformity triggers cognitive rewards and the safety we find in shared beliefs can entrench teams in the status quo.

This was originally published as a newsletter post on The Uncertainty Project. Subscribe to get posts like this in your inbox!

How ‘collective illusions’ influence decision making was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.