My experience with Minsk Improvisers Orchestra

I was always certain that only those who are trained in understanding musical notation and playing music instrument, are allowed to create music — only these special kinds of people are eligible to be called musicians.

I’m not one of this special kind of people. That’s why I’ve never even thought about playing music. However, I’m definitely into music. From my teen age, it’s a substantial part of my life; when there’s no music around, I feel like something is missing.

I first heard about Minsk Improvisers Orchestra (MIO) in 2019. It was organized by composer and musician Alexey Vorsoba in Minsk, Belarus. When I came to the first meet-up, I was surprised that apparently lack of special musical training can be not a problem, at least to some extent. Moreover, it doesn’t block one on the way towards creating (not only playing!) music. It means that the world of music is basically open to pretty much everyone who is eager to take part. Actually, during that very first meetup we started to practice in playing music. It’s not as simple as it seems from my brief description. We did it though. However, during our later meetups and rehearsals, I saw a professional musician being stuck because of absence of familiar music scores, and unable to understand what was going on and how to proceed.

There are several types of improv music; what we practiced is so-called conducted improvisation. It means that there was a conductor, who was conducting our performances. Besides performances, we had regular rehearsals where we were training our skills by means of quite a lot of exercises. It doesn’t mean that only trained members could play in the orchestra. On the contrary, during concerts, anyone was welcome to give it a try and join to play some music.

We performed several concerts on various venues. Unfortunately, MIO does not exist anymore. The reason is that most of us had to leave Belarus because of the political situation in 2020, and now are living in different counties. It was a real pleasure and one of my seminal experiences that encourages me even 2 years after.

https://medium.com/media/67e355a72493aa8e102a308625c5b660/href

Major takeaways

Due to the experience with MIO, several important discoveries can be made:

- Interaction. Improvising in an orchestra is an experience of specific interaction between its participants. It means practicing the utmost concentration on here and now. Paying full attention, one can hear one another and perceive the whole picture at any given moment.

- Silence. A keen interaction like this is important for one another to be able to decide when to step in and sound. It also allows to grasp when you’d better keep silence giving the space for others to sound. Being silent is also a form of interaction and participation. Silence is valuable and sense-making.

- Sense. Playing improv is about making sense of what an observer could perceive as a mishmash. Out of subjective interpretations and spontaneous patterns, suddenly, an unusual matter is emerging.

- Uncertainty. There is a great deal of personal freedom while playing improv. Ambiguity and uncertainty transform into a multitude of possibilities.

- Mistakes. There’s no single right answer and, hence, there are no mistakes. Instead, there are various prospects.

- Personal responsibility. Playing improv with an orchestra, regardless of being one among others, every sound from each participant counts and changes the whole picture. Since there’s a substantial degree of personal freedom, every personal decision is not only affected by the past, it also impacts the common future. We all are constantly making a common decision of what the future will look like, and there’s no way to stay aside.

Now that the idea of playing impov music is outlined, let’s get to design synthesis and the problem around it.

The problem with design synthesis

One of the most thought-provoking texts, that I came across recently, is the article by Jon Kolko. I’ll be referring to it further.

Jon Kolko " Design strategy, education & writing

The article clarifies what synthesis in design practice is. It starts with the quote that “Good designers can create normalcy out of chaos” (Veen). Sounds inspiring, doesn’t it? The problem, however, is that the mechanics of this transition, which takes place behind the scenes, is unclear:

“Yet despite the acknowledged importance of this phase of the design process, there continues to appear something magical about synthesis when encountered in professional practice: because synthesis is frequently performed privately (“in the head” or “on scratch paper”), the outcome is all that is observed, and this only after the designer has explicitly begun the form-making portion of the design process. While other aspects of the design process are visible to non-designers (such as drawing, which can be observed and generally grasped even by a naive and detached audience), synthesis is often a more insular activity, one that is less obviously understood, or even completely hidden from view.” (Kolko)

I love the quote by Albert Einstein: „There are only two ways to live your life. One is as though nothing is a miracle. The other is as though everything is a miracle.“ And yet, when it comes to design synthesis, there seems to be no magic. “These principles and methods are teachable, repeatable, and understandable. They are creative activities that actively generate intellectual value, and they are unique to the discipline of design.” (Kolko)

Apparently, the process of synthesis can be formalized. This is what really sounds inspiring to me. It means that we, designers, can understand how it works, develop this skill, and teach others.

Synthesis within a design process

There can be quite a lot of ways to describe a design process. For the sake of this article, the interplay between analysis and synthesis is essential and used for this purpose.

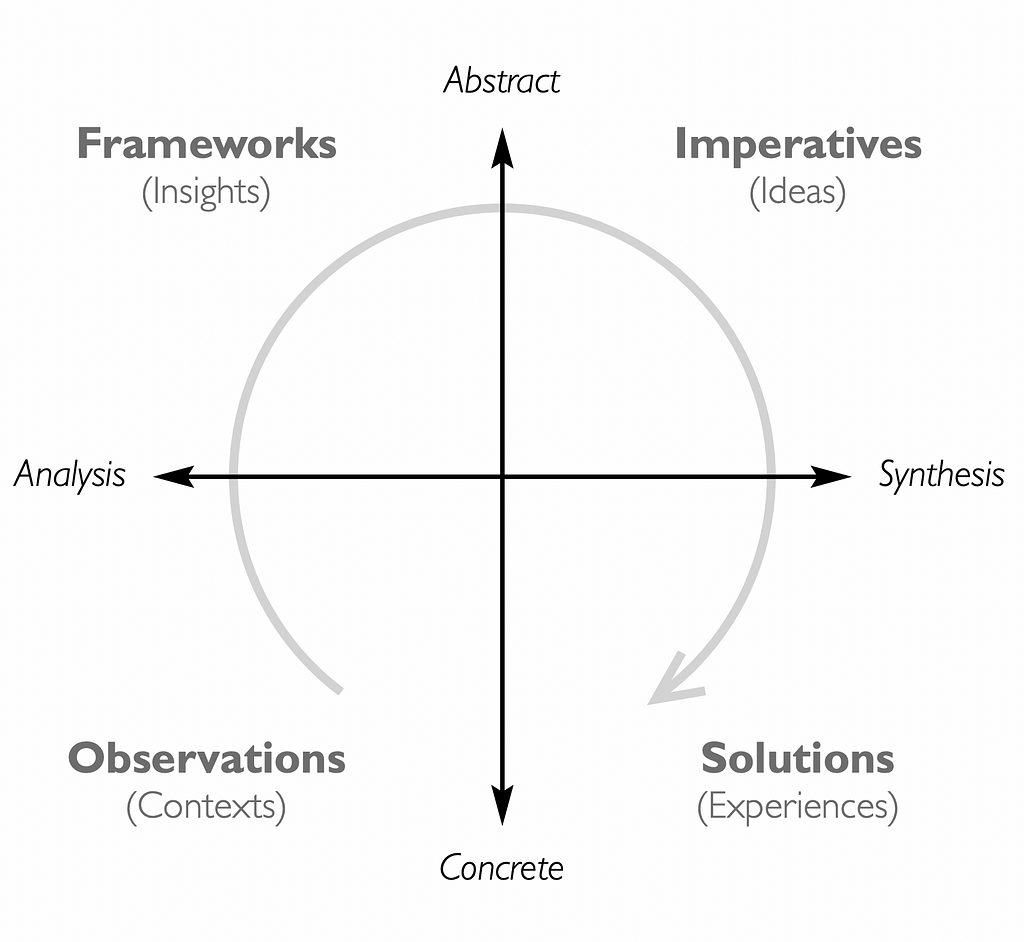

As The Innovation Process as Learning Model suggests, “this process moves its participants between the concrete and the abstract worlds, and it alternately uses analysis and synthesis to generate new products, services, business models, and other designs”. It can be organized as a two-by-two matrix.

“The left column represents analysis (the problem, current situation, research, constituent needs, context). The right column represents synthesis (the solution, preferred future, concept, proposed response, form). The bottom row represents the concrete world we inhabit or could inhabit. The top row represents abstractions, models of what is or what could be, which we imagine and share with others.” (The Analysis-Synthesis Bridge Model)

Based on this model, it is easier to spot a designer’s core abilities.

Synthesis among designer’s core abilities

There are 8 core designer’s abilities listed by Stanford d.school.

Two of them — navigate ambiguity and synthesize information — are particularly relevant for understanding the essence of the process that was referred to as “creating normalcy out of chaos”. These two abilities are described in the following manner:

- Navigate ambiguity is “the ability to recognize and persist in the discomfort of not knowing, and develop tactics to overcome ambiguity when needed. <…> it involves being present in the moment, re-framing problems, and finding patterns in information.”

- Synthesize information is “the ability to make sense of information and find insight and opportunity within. This ability requires skills in developing frameworks, maps, and abductive thinking. It takes time and is interdependent with navigating ambiguity.”

So, in terms of design synthesis we have two related abilities which will be considered in the first place. There are two more abilities that are relevant as well: Learn from others and Experiment rapidly. We’ll take them into account a bit later.

Let’s get back to the Jon Kolko’s article and learn more about design synthesis.

Design synthesis explained

“Synthesis is an abductive sense making process”, states the article that I’m referring to. Synthesis there is described starting from logical and cognitive background to specific actions.

Sensemaking

“Klein, Moon, and Hoffman define sensemaking as ‘a motivated, continuous effort to understand connections (which can be among people, places, and events) in order to anticipate their trajectories and act effectively.’ <…> emphasis is placed on finding relationships and patterns between elements, and forcing an external view of things. <…> In all of the methods, it is less important to be “accurate” and more important to give some abstract and tangible form to the ideas, thoughts and reflections.”

Let’s do some analysis and distill several essential characteristics of sensemaking. They are:

- Content: a process of understanding relationships and patterns between elements

- Direction: a step from concrete towards the abstract realm

- Aim: to forge a tangible form to the ideas & thoughts to be able to externalize them.

Abduction

“Abduction can be thought of as the argument to the best explanation. It is the hypothesis that makes the most sense given observed phenomenon or data and based on prior experience. Abduction is a logical way of considering inference or “best guess” leaps. Consider the example:

When I do A, B occurs:

I’ve done something like A before, but the circumstances weren’t exactly the same.

I’ve seen something like B before, but the circumstances weren’t exactly the same.

I’m able to abduct that C is the reason B is occurring.

Unlike deduction or induction, abductive logic allows for the creation of new knowledge and insight — C is introduced as a best guess for why B is occurring, yet C is not part of the original set of premises. And unlike deduction, but similarly true to induction, the conclusions from an abductive argument might turn out to be false, even if the premises are true.”

The following several characteristics of abduction are essential here:

- Content: introduced hypothesis as a result of previous experience in reasoning about the original premises, not the original premises themselves

- Aim: to pursue the best explanation of why something is the case

- Direction: from some original premises towards a hypothetical explanation, possibly wrong though.

A synthesis framework

The theoretical assumptions described above get realized in practice via specific types of actions. There are three of them:

- Prioritizing: “Data prioritization will eventually identify multiple elements that can be seen as complementary, and thus a hierarchical data structure is created”.

- Judging: “…the definition of relevance, as the designer will pass the gathered data “through a large sieve” in order to determine what is most significant in the current problem-solving context”.

- Forging connections: “Identifying a relationship forces the introduction of a credible (although rarely validated) story of why the elements are related”.

Overlap between design practice & playing improv

Overlap in constraints

Similar to design ideas, improv music is not something coming out of the blue. What we were performing in MIO was definitely not merely noise consisting of a random sounds:

- Improv is not accidental: the orchestra had an idea of what to play. There was a certain theme for each piece of music.

- Improv is not meaningless: each musician understood how to play a particular piece of music. We spent a great deal of time during rehearsals to experiment, train various techniques, and master interplay among ourselves.

Thus, the music we made in MIO was the fruit of deliberate efforts and plenty of sensible decisions. The same applies to any design project that is also neither accidental nor meaningless; it takes place within well-defined constraints that are rooted in solid answers to Why? Who? When? Where? What? How? questions.

Overlap in actions

There is an overlap between playing improv music and design in terms of actions. The essential actions while playing improv are as follows:

- embracing the lack of the perfect plan and adapting to what comes next

- understanding connections between seemingly unrelated pieces and combining them into chunks

- determining the most significant prospect to follow

- derive sense out of meaning

- making hypotheses and experimenting on the go

- revealing new possibilities through changing perspectives.

Basically, this list of actions corresponds to the design synthesis framework described above.

Overlap in abilities

Actions are performed due to one’s personal abilities. Hence, there’s an underlying overlap that embrace abilities ensuring those corresponding actions. Remember two abilities from the d.school’s list — Navigate ambiguity and Synthesize information? Overlaping actions listed above fit nicely in the descriptions of those two abilities. Thus, navigating ambiguity and synthesizing information can be considered as common abilities for playing improv and design synthesis.

Interestingly, all 8 core designer’s abilities mentioned above are referred to as “higher-order set of design abilities that represent creative competencies” (Introduction to Design Abilities Suite). It means that they are applicable to creativity as a human feature, regardless of a particular application or a domain. Therefore, being a general set of creative competences, they can potentially be trained or exercised through activities other than design per se.

Why playing improv music can be helpful?

What is particularly inspiring is that the ability to synthesize in design can potentially be trained by means of playing improv.

Why this can be helpful?

Firstly, because playing improv music in a group of people is highly accessible. Admission requirements to participate are quite low. What is necessary is open-mindedness, curiosity, interest in music; no special music training is required, at least to some extent. It means that novice designers or design students can start practicing without prior training or without having any idea of a specific design process.

Secondly, playing improv can help in exercising creative competences which are directly related to design synthesis — Navigate ambiguity and Synthesize information.

Thirdly, other creative competences as per d.school can be exercised as well:

- Experimenting rapidly: “This ability is about being able to quickly generate ideas — whether written, drawn, or built”. While playing improv music, one should make tons of decisions per unit of time, test them and receive feedback in order to start a new loop of decision making.

- Learning from others (people and contexts): “This means empathizing with and embracing diverse viewpoints, testing new ideas with others, and observing and learning from unfamiliar contexts”. For non-musicians, playing music in a group is a great way to learn from other people, while playing music at all is both a challenge and a possibility to learn from other contexts.

Conclusion

Playing improv music seems like a promising method to train the ability to synthesize and even more, involving 4 out of 8 designer’s abilities from the d.school’s list:

- Synthesize information

- Navigate ambiguity

- Learning from others (people and contexts)

- Experimenting rapidly.

Once started playing, there’s much more one can learn and derive personally. And I hope, Alexey Vorsoba (MIO founder) will soon finish his book and shed more light on many fascinating ideas around improv music.

How playing improvised music can train the ability to synthesize in design was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.