Urban planners have been designing for human experiences for nearly 200 years, UI/UX designers can learn from this

It’s July of 2016. The augmented reality game Pokémon GO was just released. Within days, millions of teens and Millennials are suddenly spending hour upon hour outside in search of rare Pokémon, battling one another, and living in a virtual reality fantasy-world manifested into our physical one. The game would go on to spawn memes, promotional events, and even some controversy.

Pokémon GO was hardly the first piece of software to interface with our physical world from a digital vantage point, but it was pioneering in overlaying user experiences with the physical limitations of the built world. People in rural communities had fewer locations to catch Pokémon, buy services, or battle their friends. Certain landmarks in the game became extremely popular and brought crowds to physical spaces that couldn’t support that number of people. Essential elements of the game became associated with churches, businesses, parks, museums, and other parts of the city. As a result, access and mobility became essential for players to get the most out of the mobile game.

The duel realities of Pokémon GO, being both physical and virtual, sparked an idea for me in 2016. At the time, I was working in an architecture firm, spending some of my time working in urban design. Pokémon GO materialized real user experience design problems into the physical world. Conventional applications might have to solve for clicks and dialog boxes, but Pokémon GO had to translate gaming elements into a physical reality. Throughput was as much about data as it was people now. User pathways were now literal sidewalks. The user interface was a reskinning of our physical world. The idea dawned on me in those early days of Pokémon GO; our applications, software, and digital services all operate a lot like the cities we live in.

Applications are Cities in Cyberspace

Today’s world of websites, mobile apps, and digital services has permeated nearly every aspect of life. Most applications don’t literally interact with our world like Pokémon GO, but they certainly resemble the ways we move about our physical cities. That summer of 2016 made it incredibly clear to me just how city-like software and applications can be. The user journey of going out into your town or city to find a store to buy new shoes is not all that different from ordering them from an e-commerce site. In fact, the relatively young field of user design unknowingly borrows a lot of fundamentals of the urban design that facilitates this type of real-world transaction. I believe this is primarily because as services move to the digital world, the problems they solve are still grounded in reality. We have “virtual shopping carts,” “home screens,” “email,” and so many other digital artifacts that mirror their physical counterparts both in name and function. Designers have digitized elements and services of the city and unknowingly, replicated the city in a virtual setting.

Digital Clones of Physical Places

On the one hand, I mean much of this metaphorically. Obviously, we aren’t building digital streets, stop signs, sidewalks, parks, sewage plants, or court houses. That said, it’s not hard to think of a digital equivalent to any urban element. E-commerce was born out of grocery stores, malls, and shops. Government sites are simply digital copies of their physical selves. The Steam shop replaced GameStop. Google’s search functions clearly have their roots in the experiences of libraries. The data and functions that stitch this all together resemble their physical counterparts too, such as streets, bridges, railways and more.

Cities also work well as a parallel for our virtual world because the internet is a reflection of our physical reality. We primarily use this technology to do things we used to do physically, at a societal scale. The internet has essentially eliminated the friction of physical distance from a vast portion of our lives, but is still foundationally predicated on movement through space (cyberspace, in this case).

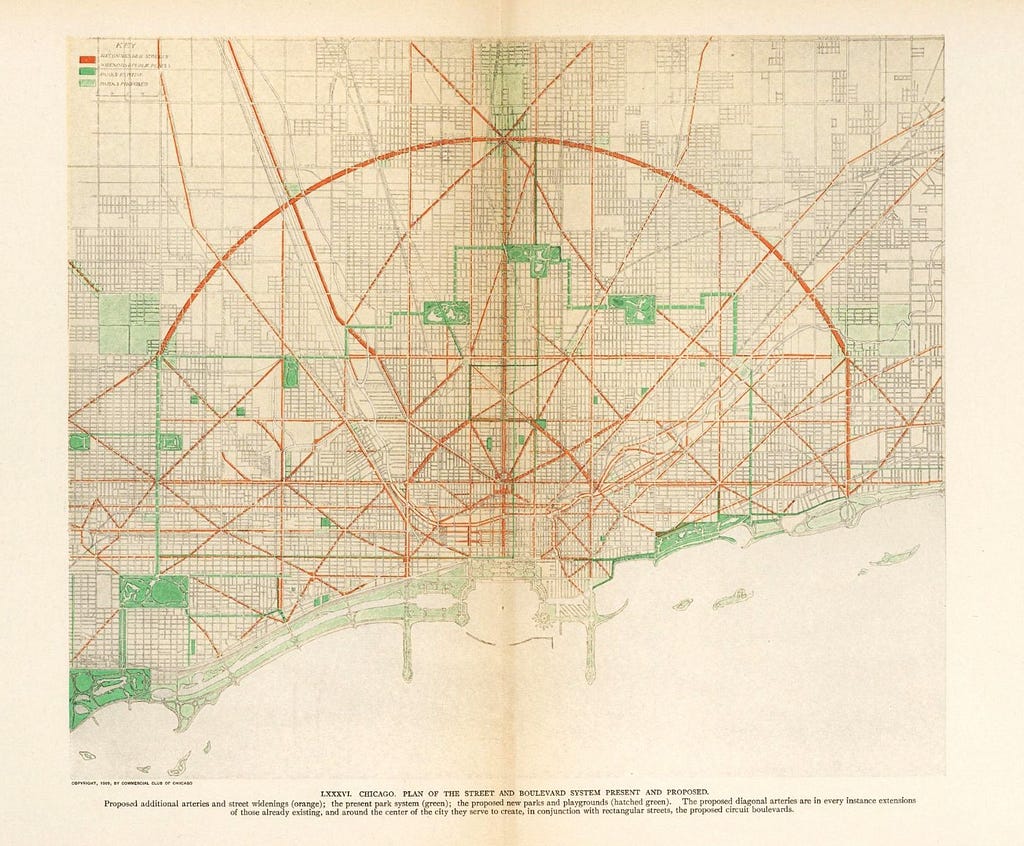

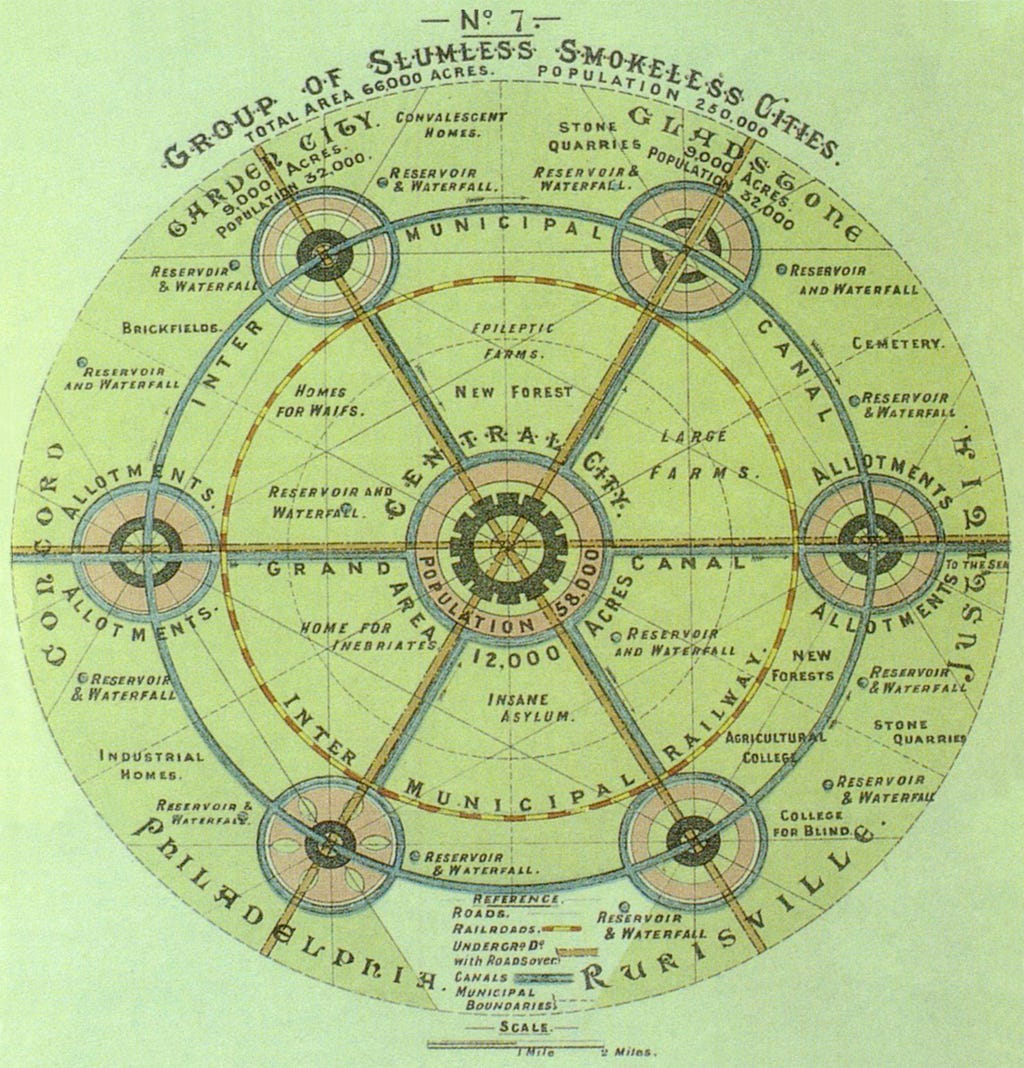

Cities also represent the same central goal of digital service design — moving about space. Consider the above 1909 “Burnham Plan” for Chicago. The focus of this map is on the interconnectivity of residential streets with a Parisian-style “wheel and spoke” design for regional mobility, which was popularized by Ebenezer Howard’s “Garden City”, seen below. Every city planner, since the dawn of the practice, has wrestled with the fundamental problem of mobility: how do we move people about a city in a manner that is logical, pleasant, and efficient. In our digital world, UX designers focus on the same thing for users of their applications, simply in the virtual context.

Of course, digital products and services are predominantly not focused on literal mobility, but rather, the metaphorical need to transcend space and time. Said another way, we traverse cyberspace through these services in an effort to reduce time and energy spent. Think about the vast amount of time and mobility that the internet saves us on various trivial and non-trivial tasks. Learning how to knit, fixing a leaking faucet, chatting with a friend in another nation, researching Native American history, watching sports highlights, booking trips to see your grandmother, and so many countless other things have their transactional friction essentially reduced to nothing because of the internet and the services that enable us to use it. The metaphysical plane of time is now the vector of travel in a digital environment. Clicks, queuing, and cognitive load are the “traffic congestion” of digital design.

In short, our apps, websites, and digital services reflect our cities because they were designed to replace physical tasks historically performed in the context of civic life. The gradual evolution of these digital equivalents has brought with it, fragments of physical artifacts, embedding echos of themselves into these digital contexts. Like cities, these services connect us, foster culture and art, maximize our collective energy, facilitate transactions, and enable efficient movement in space.

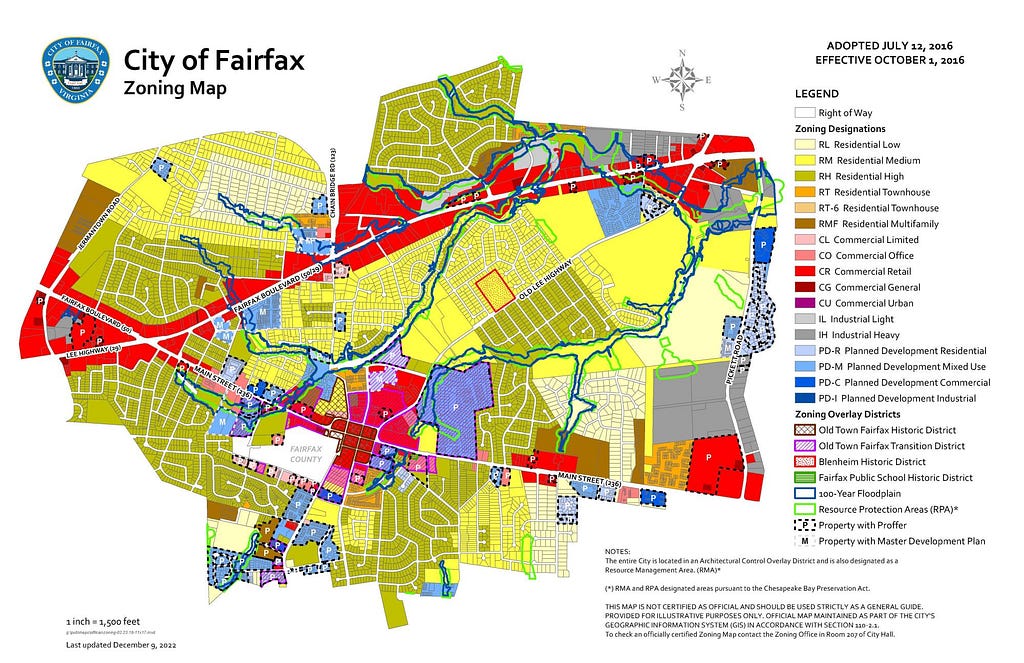

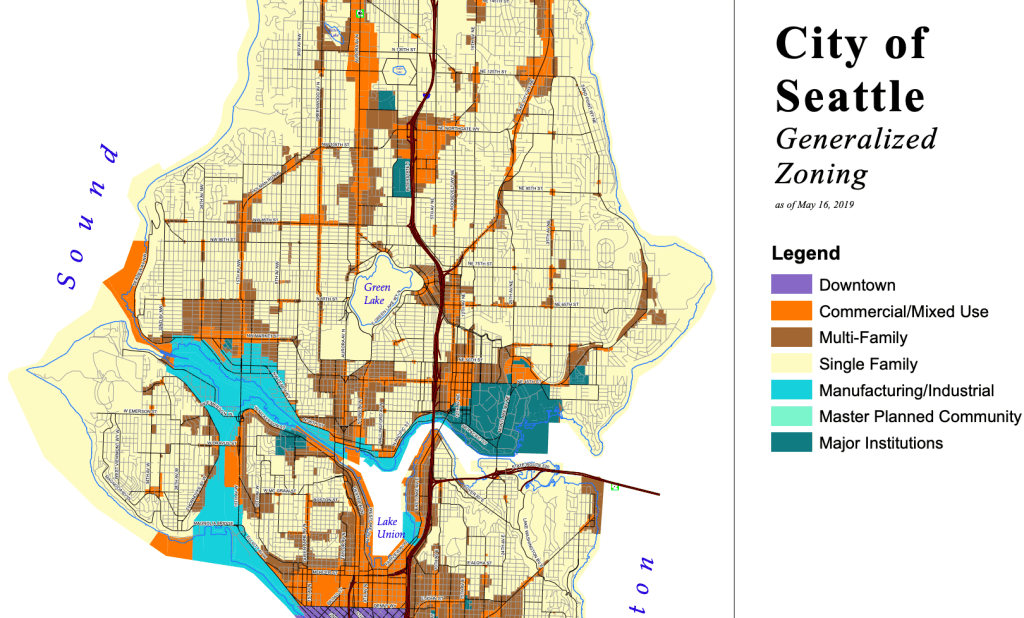

Urban planners use zoning to prescribe land uses that make sense in the context of their surroundings. Much like a design system, site map, or “visual grammar” library, land use zoning creates clear classifications of spaces and functions in cities as well. Our streets, highways, rail lines, and sidewalks focus on connection between spaces. We have residential, commercial, and industrial building classifications. Each serves a different purpose or function. Cities have shops, parks, museums, government buildings, concert halls, and so many other types of recreational space. Infrastructure like sewers, powerlines, and telecom provide vital services that keep the action of society moving. Like Lego bricks, the pieces of our cities are organized and assembled to create fascinating and wonderful works of art that follow patterns of structure, function, size, and much more.

Consider your favorite app. Any service will do: Spotify, Gmail, TikTok, Duolingo. Even an app that you dislike will work. Apps can be broken down into components and smaller components and so forth, just like a city. Home screens, profile sections, security settings, tasks, notifications, chat features, help sections, and terms of service all look a lot like different types of buildings or districts in a city. They’re all connected by clicks and swipes, a lot like how streets and roads connect a city. Under the hood is a massive network of data, API calls, AI decisions, and rules logic. Just like our public infrastructure, this keeps our apps running smoothly without us noticing.

Like cities, there are also bad examples of how to execute these designs. For example, transit planning is critical for ensuring cities avoid vehicle congestion and allow citizens increased access to the places they need to go. Ask anyone what their list of top annoyances is and “being stuck in traffic” is probably in the mix. Applications with confusing service pathways follow similar patterns to poorly designed freeways or confusing one-way streets. Some might also remember, last year, the surge of people trying to buy Taylor Swift tickets crashed Ticketmaster’s servers, just like a traffic jam.

How about patterns of data storage? A typical profile screen has several subfolders of information about a user. It’s frustrating when these items are poorly organized or don’t follow a clear order of classification. Land use planning ensures our cities have zoning codes for similar reasons. Residential homes are separated from industrial zones and commercial parks both for safety and uniformity of services. Waste treatment plants are kept far away from schools and homes to protect people much in the same way sensitive user information is stored securely in specific subfolders and not scattered about a site.

Proximity and access to necessary information is also critical in product design. API calls for necessary data in a moment’s notice is essential to every app on our phones today. This is reminiscent of the “15-minute-city” which has gotten more attention in the past decade. The central premise is this: all homes should be a 15 minute walk or bike ride away from all essential services and third spaces. Hospitals, grocery stores, schools, etc. all fall into this broad category of “essential”. Third spaces are public places outside of the home where people can gather and engage with little or no money spent. Places like coffee shops, libraries, parks, town halls, and public plazas are good examples.

The human-centric design movement of urban planning is mirrored in the accessibility movement within UI design. Swipes, gestures, buttons, icons and much more are designed with the user as the central stakeholder. Accessible design principles in the digital world look a lot like ADA compliance in the built world, both emphasizing design for the better of all people, not just the able-bodied. Clear, resilient, and excellent digital design, like architecture and civic design, quite literally improves the material quality of life for all people.

The Building of a Cyberspace City

The above examples are mostly a list of clever metaphors or parallels between cities and the apps we use. The next step in understanding these similarities involves understanding some basics in urban planning theory and then moving on to understand practices used in the field. More than just being remarkably analogous, I believe the city offers a “physical” view of the largely invisible entities of software.

This brings me back to Pokémon GO. As a service, the application effectively places an invisible “digital” layer onto the physical world. When players need to perform a task, it isn’t just a swipe or click away; players have to take to the streets and interact with the “real world”. This rare peak at the merging of the two realms, to me, feels like a brief sighting of a parallel dimension colliding with our own.

As this series evolves, I want to look at urban planning values, practitioners, tools, and theory and draw clear connections between civic design and product design. The practice of urban planning is over 100 years old, and cities are clearly centuries old; if they share so much in common with digital product design, then we owe it to ourselves to explore the best practices of the former and apply them to the latter.

An urban planner’s guide to designing software was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.