Setting a course for better image-generation tools.

For the past year, I’ve been experimenting with several AI art image generating systems: VQGAN+CLIP and Diffusion notebooks on Google Colab, Midjourney, a text-based image-generation system, built on top of Discord, and DALL·E, a web-based image creation tool from OpenAI. A user experience designer by trade, I’m interested not just in the resulting images, but also in how these new technologies shape the creative process.

I’ve captured some guidance below in an effort to spark discussion of how we might set a course for better AI art interactions. First and foremost, this article is intended for those implementing image generation systems. I hope the principles below will lead to the development of even better, more human-friendly tools. For those artists new to image generation, you might also come away with some useful techniques to further develop your craft.

It’s incredible that a picture can be generated from a single text phrase and while many are satisfied to stop there, other creators want more control over the images. Even in these early days, there are already multiple ways to shape the AI’s results:

Prompt engineering

While neither a separate feature nor an integrated part of the interfaces, there are many independent guides and image tests that aim to provide style names and other key words that yield desired results. Midjourney also published some helpful prompting tips.

Size and quality

When dealing with images, there are inevitable trade-offs between size, quality, and speed. Built on cloud-based systems, we’re able to use hardware we wouldn’t ordinarily have access to, enabling significantly faster image generation. Both Midjourney and DALL·E are incredibly fast. DALL·E somehow manages to generate 6 high-quality images in seconds. But given finite resources (and they are always finite), I actually prefer Midjourney’s approach of generating initial thumbnails that can be optionally “upscaled” later.

Aspect ratio

Limits of the technology meant that several of the early VQGAN+CLIP and all of the diffusion Colabs restricted the aspect ratio to 1:1 (square). Midjourney lets you specify custom aspect ratios and DALL·E is stuck in squares. While I understand there are technical hurdles to overcome, very few images look best in a square format. Full flexibility is best, but at a minimum, options for portrait and landscape are extremely valuable for art creation.

Initial images

VQGAN+CLIP and Midjourney let you start your art creation from an image, uploaded or linked, respectively. While somewhat tedious, I generally found uploading to the Colabs easier than the Midjourney approach, which requires a web link for the image. DALL·E allows you to upload an image for future generation of variants or editing. This is easy enough, but the image storage process is unclear.

Variants

Midjourney and DALL·E both let you riff of of an image, injecting an unknown quantity of randomness that sets the image off in a certain direction. While it lacks precision, it does enable a kind of automatic iteration. The ease of the interaction is quite compelling, but in my experience, it often takes multiple branching variant generations to get anything useful and often, I give up before it reaches that point.

Editing & inpainting

The code- and text-based nature of Google Colabs and Midjourney, respectively don’t lend themselves to direct image intervention.

With DALL·E, it’s possible to draw an area right on the image and reissue a prompt to modify (or add to) that part of the image. This functionality may be my favourite DALL·E feature. It’s useful, particularly to get an image to an end state by eliminating something you don’t want in there. It’s also useful for creating large image composites, preserving an edge of an image and extending the opposite end. This currently involves image processing outside of DALL·E, but it might be a reasonable feature to consider integrating directly in the interface.

Some creative folks have also begun generating selfie variants by erasing the background of an uploaded image and regenerating it.

As much as I appreciate the feature, it would be even better with a stronger indicator within “edit mode”. It wasn’t immediately clear to me why a totally different prompt was rendering an image very similar to the previous one. The chip in the search bar is a good pattern, but I completely missed it when I came back to rerun a new prompt.

While not inherent to the system, many early VQGAN+CLIP Colabs displayed in-progress images at various intervals, making it also possible to export these frames together in sequence as a video. There’s something a bit magical about watching images emerge from nothingness.

Progressive display was also useful in determining when to end the process of generation. I would typically set the number of iterations artificially high and then manually cut off the process when it reached I was happy with or when it seemed like returns were diminishing.

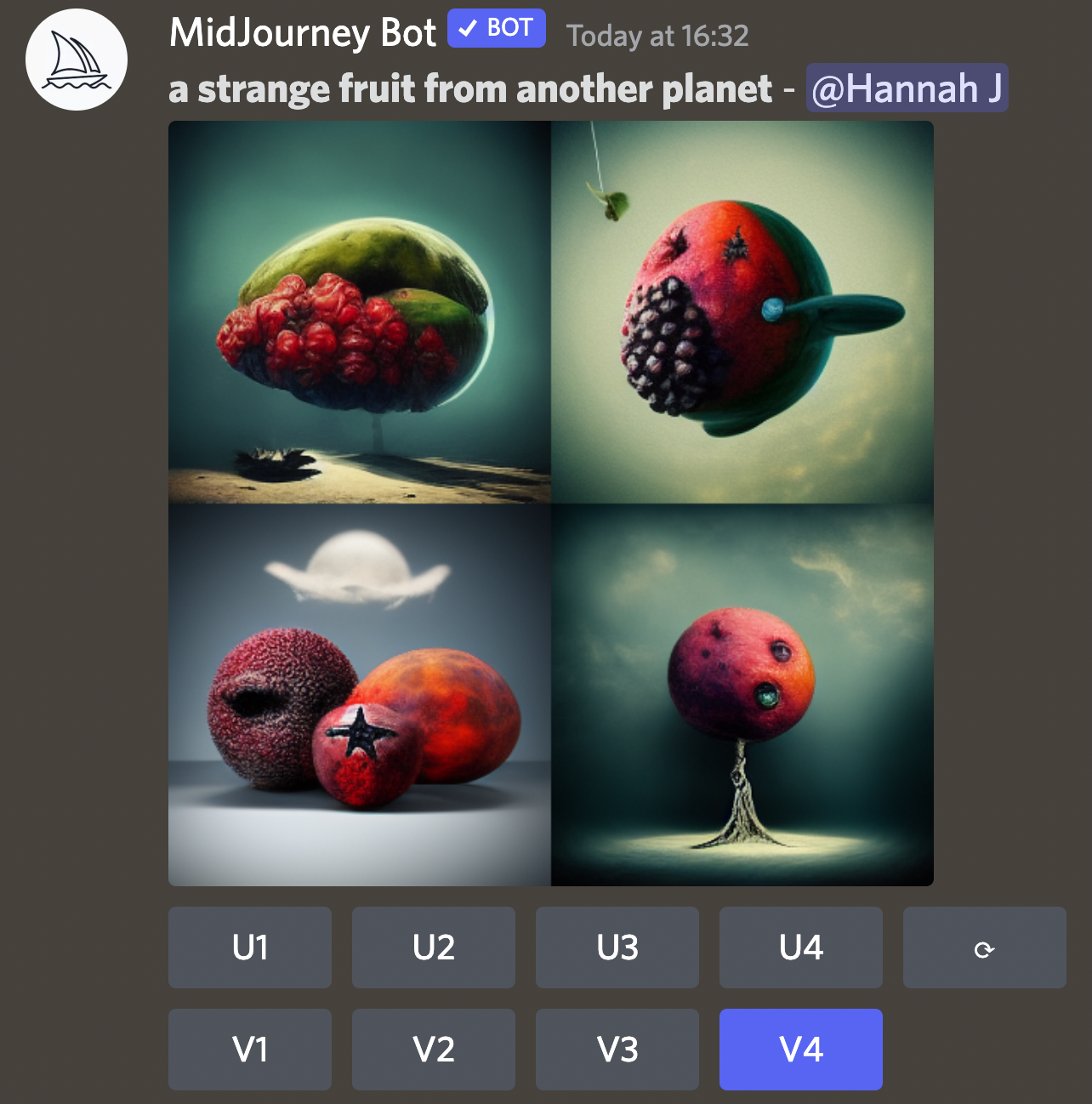

Once a request is issued to the bot, Midjourney displays progress in a similar fashion, progressively refining and adding detail for both the initial 4 image thumbnails or 1 upscaled image. This happens very quickly in “fast” mode. In general, as these systems get more efficient — or more resources are devoted to processing — less time is needed for generation.There is a flag you can set to stop image generation at an earlier percentage, but you must specify this when you make the prompt request. Similarly, you can opt into having a progress video saved, if you make the choice in advance.

DALL·E doesn’t provide in-progress images. It’s quite fast and since you can’t stop image generation part-way through anyway, it’s not a serious impediment. It does feel just a little bit more dull, though.

Creating images is just one part of the experience. If they’re any good (or entertainingly bad), people want to save, download, or share them. This process should be easy and it should match expectations to prevent accidental loss.

The Google Colab system itself is really just a shell, so it will do absolutely nothing to save any images (or image progress) that you don’t implement yourself. Some helpful developers have added functionality to connect directly with Google Drive, enabling auto saving or providing periodic downloads.

Midjourney is an open sharing community by default unless you pay extra for private mode. Images are typically created in a busy Discord channel, often with many people generating simultaneously. This can give the images a sort of ephemeral feeling — they scroll by as new requests come in and more images are generated. There are work-arounds: you can work in a private channel or by DMing the bot, but Discord can still be a frustrating interface, particularly for later retrieval. To get around this (and probably for other smart reasons), the Midjourney team created a web-based gallery for your images, both variant thumbnails and image upscales. While there isn’t yet a bulk download option, it’s still simpler to save images from the web.

My only outstanding question on the Midjourney front is about image retention. I assume I won’t be able to go back in time indefinitely, but I hope those limits (if or when they exist ) are made clear

With DALL·E, I was initially very excited to see a panel on the right side with the previously-run image collections, but later realized that these were somewhat ephemeral and only the most recent ones remained visible. This was unfortunate because I would have done a more thorough job of saving or downloading had I known these were temporary.

The distinction between Save, Download, and Share options are clear enough with some thought, but the first couple of times I expected the Save button to kick off a download — perhaps as it does with Midjourney. I would like to better understand any limits on Saving.

Craiyon (formerly DALL·E mini) helpfully offers a button to capture a screenshot. Given the frequency with which I wanted to capture all of the results simultaneously using DALL·E, an option to grab the set — even just as thumbnails — seems like a potentially worthwhile feature addition.

While unlimited options would be nice, AI art creation is resource intensive, so it’s entirely reasonable that platforms enforce limits. Providing information upfront helps users plan their usage and avoid the unpleasant surprise and disappointment being abruptly cut off as soon as they’re hooked.

The most opaque of all systems I’ve used so far, the early days of image generation were ripe with silent slowdowns and cryptic Google Colab error messages. Google has various paid tiers that offer progressively more powerful processors, but with sufficiently cagey language, that you’re never really sure what’s going on or where the limits are.

Though rapidly evolving, Midjourney has managed to do a reasonably good job of articulating the limits, with the exception of their “unlimited” label. My usage has been exceptionally heavy, meaning that fairly early in month 1 of the Standard plan, I hit the cap on “fast” image generation and got relegated to “relax” mode. This is entirely fair, but I (and most users) don’t read the fine print, so I wish the limits had been more in-my-face. Another option would be to give users a heads-up some percentage into their usage — particularly for those out of control users who unknowingly use up their quota in the first week. 😅

When I got access to DALL·E, I very quickly blew through my 50 images. I would have been more thoughtful about it had I had any indication that I would run out. My preference would be for limits to be obvious from the get-go, but again, I’d settle for periodic warnings or at the very least, a warning with ~10 image generations left.

One other small nit about DALL·E’s warning system: the use of a disappearing toast is a little annoying. I didn’t pay much attention to the time window and was left wondered when I could get my next fix– I mean resume my image generation experiments. This could instead be avoided with more transparency around the policies and limits in the first place.

In contrast with Midjourney and the early Colabs, DALL·E feels more anchored to realism, often ignoring parts of the prompt in favour of image coherence. For prompts that don’t specify a style, the default appears to more strongly biassed towards photographic accuracy.

This approach may be better suited to more practical applications, but doesn’t seem to generate as many novel interpretations, which in turn, feels a little less interesting and, frankly, less magical. It puts more of the creative work back on the user, which I think may turn out to be a good thing… for some users as it provides with it more control.

It would be helpful to be able to dial these properties up or down, for example, to specify how realistic or fantastical you want the image to be, or how divergent or convergent to make variants. It’s often possible to weight prompt terms using VQGAN+CLIP and Midjourney by appending numbers to different words or phrases (e.g. “dog:1 | in the style of Edward Hopper: 2”).

On a continuum from least to most developed creative exploration, I could see using something like Midjourney early on, then moving towards a tool like DALL·E once I’d arrived at a concept I was happy with.

Software developers set policies around how their tools and services can be used. The early Google Colabs had no stated restrictions. When Midjourney started to get traction, they posted community guidelines and restricted some text inputs automatically to avoid prompts that are “inherently disrespectful, aggressive, or otherwise abusive”. The rules seem to come from good intentions, put in place to support a welcoming place for all ages. But they are not without trade-offs. In the context of art, any limitations (particularly blanket term blocking) can come across as censorship.

DALL·E content policy is even more restrictive. I attempted to run ‘black and white forest destruction lino cut print’, which was in violation of the content policy, which was helpfully linked. I deduced that “destruction” was the offending word — ‘black and white forest fire lino cut print’ worked just fine. DALL·E also prohibits generating the likeness of any public figures, including celebrities or photorealistic Keanu Reeves centaurs. 😒 For what it’s worth, DALL·E doesn’t do a great job of centaurs in general, anyway.

I can understand the motivations and I’m not opposed to rules that prevent abuse, but I have to wonder if they may be motivated more by a desire to control marketing, PR messaging, and limit legal liability than genuine concern for others. In any case, given a creative context, I wish there was just a little bit more flexibility, perhaps with more active moderation rather than large, blanket restrictions. With both Midjourney and DALL·E, I would love an option to appeal a specific prompt. In many cases, context matters. I have to believe Keanu would be OK with this.

I don’t generate images for profit, so I’ve had the privilege of largely ignoring issues related image usage rights, but it is interesting to see how it shakes out across systems.

Early Colabs made no mention of ownership, leaving ownership to the interpretation of the users. As NFTs and other commercial uses took off, some developers added disclaimers or restrictions for images generated with their systems. Midjourney took a clearer stance from the get-go, building in usage rules, with plans at different price points, charging more commercial use. OpenAI retains all rights to images created by DALL·E users — unfortunate, but not surprising. With new technology, copyright rules and legal interpretations are less clear, so they may also just being cautious.

While my own (entirely non-legal: I am not a lawyer, this is not legal advice) opinion is that the resulting images should meet any reasonable definition of ‘transformative’ required to be classified as copyright infringing, the models from which images are generated seem, if not legally blurry, at least ethically complex. At a minimum, decisions around the fair use of images used in a model should be made in consultation with the artists whose work is used as input for these systems. To be honest though, I’m not sure how that can be done in a practical sense, at least not at the scale necessary to be meaningful at this point. That ship may have already sailed.

It’s possibly even more concerning that any individual company could maintain ownership over these gigantic models. Surely artists on both sides deserve better than systems take all of the content and provide the bare minimum in return.

Early image generation tools appear to be getting by just fine on novelty. Despite my luddite tendencies, I continue to be amazed by the evolution of this technology. While I don’t think everyone will become obsessed with image generation to the extent that I have, I do think a wide range of people could find delight — or possibly utility— in it.

But to achieve this reach, we’ll need to give far more thought to the actual accessibility of these systems. Can they be used by low-vision users? What about those with cognitive or motor impairments? Do non-tech-oriented artists even want to try these tools? What other barriers to entry are we not even aware of.

Developers should also start to develop a clearer understanding of the problem (or sets of problems) their technology can solve. Image generation systems provide beginners with the means to visualize ideas without arts training, but they can also enable precision iteration for more experienced artists and commercial designers, and everything in between. These use cases may be different enough to warrant different access points, features, and possibly entirely different modes of interaction.

At this point, it would be naive to assume we have any idea of how these systems will be used in the future, but my hope is that we steer them in the direction of inclusion.