Public and professional perceptions of artificial intelligence.

TL; DR. AI is rapidly evolving, helping us make better decisions and perform various tasks and increasingly doing so autonomously.

Will humans eventually be enslaved by machines that become self-aware, like in a science fiction movie? AI taking over the world seems to be a recurring theme in pop culture, so we might wonder whether most people view it that way.

I chose to dive into numbers to find answers to the multitude of questions we can have about it, gathering data from two perspectives: public and professional perceptions of artificial intelligence.

Last year, the European Commission adopted the first-ever legal framework on artificial intelligence, which addresses the risks of AI and positions Europe to play a leading role.

It was shortly followed by the global standard set by UNESCO on the ethics of artificial intelligence.

These two events landmark a step forward in thinking about the uses of AI, to agree on exactly which values need to be fixed and which rules need to be enforced.

Many frameworks and guidelines exist, but they are implemented unevenly, and none are truly global.

This is why the initiatives of the European Commission and UNESCO are essential to provide concrete measures to ensure that AI is deployed for the sole purpose of improving the quality of our lives.

This Recommendation aims to provide a basis to make AI systems work for the good of humanity, individuals, societies and the environment and ecosystems, and to prevent harm. It also aims at stimulating the peaceful use of AI systems.

In addition to the existing ethical frameworks regarding AI around the world, this Recommendation aims to bring a globally accepted normative instrument that focuses not only on the articulation of values and principles but also on their practical realization, via concrete policy recommendations, with a strong emphasis on inclusion issues of gender equality and protection of the environment and ecosystems.

The increasing omnipresence of AI in our daily lives is producing significant results. Sometimes unnoticed but often with profound consequences, it transforms our societies and challenges what it means to be human.

We see AI being used by major companies in retail, finance, healthcare, public transport and many more domains, to improve their services and make their processes more efficient.

In 2017 Andrew Ng went as far as saying “just as electricity transformed almost everything 100 years ago, today I actually have a hard time thinking of an industry that I don’t think AI will transform in the next several years.”

Technology is evolving rapidly, and AI will likely do the same as its applicability and problem-solving potential become clearer. AI will not only help us to perform various tasks and make better decisions, but it will increasingly do so autonomously.

Is AI a good or bad thing?

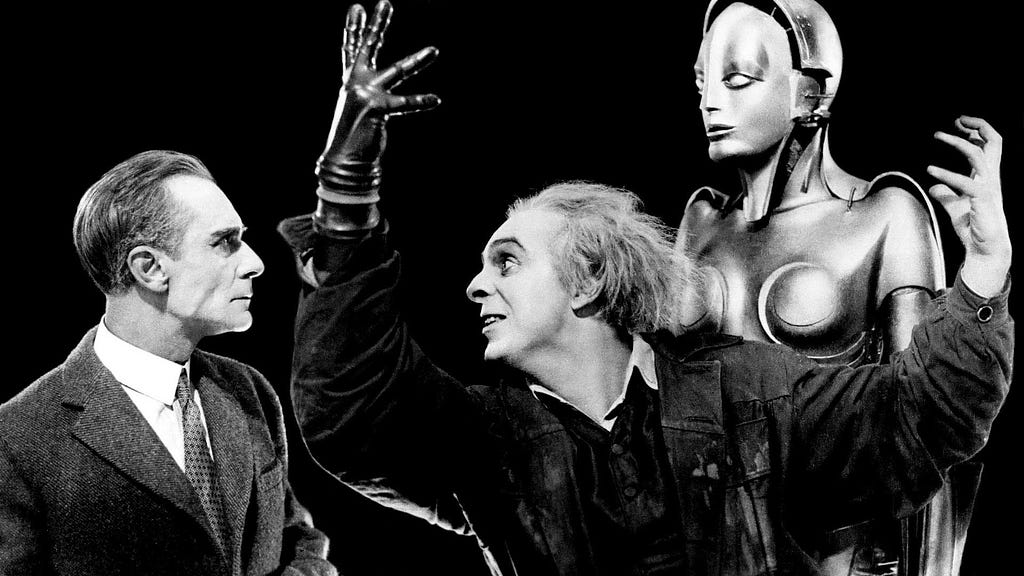

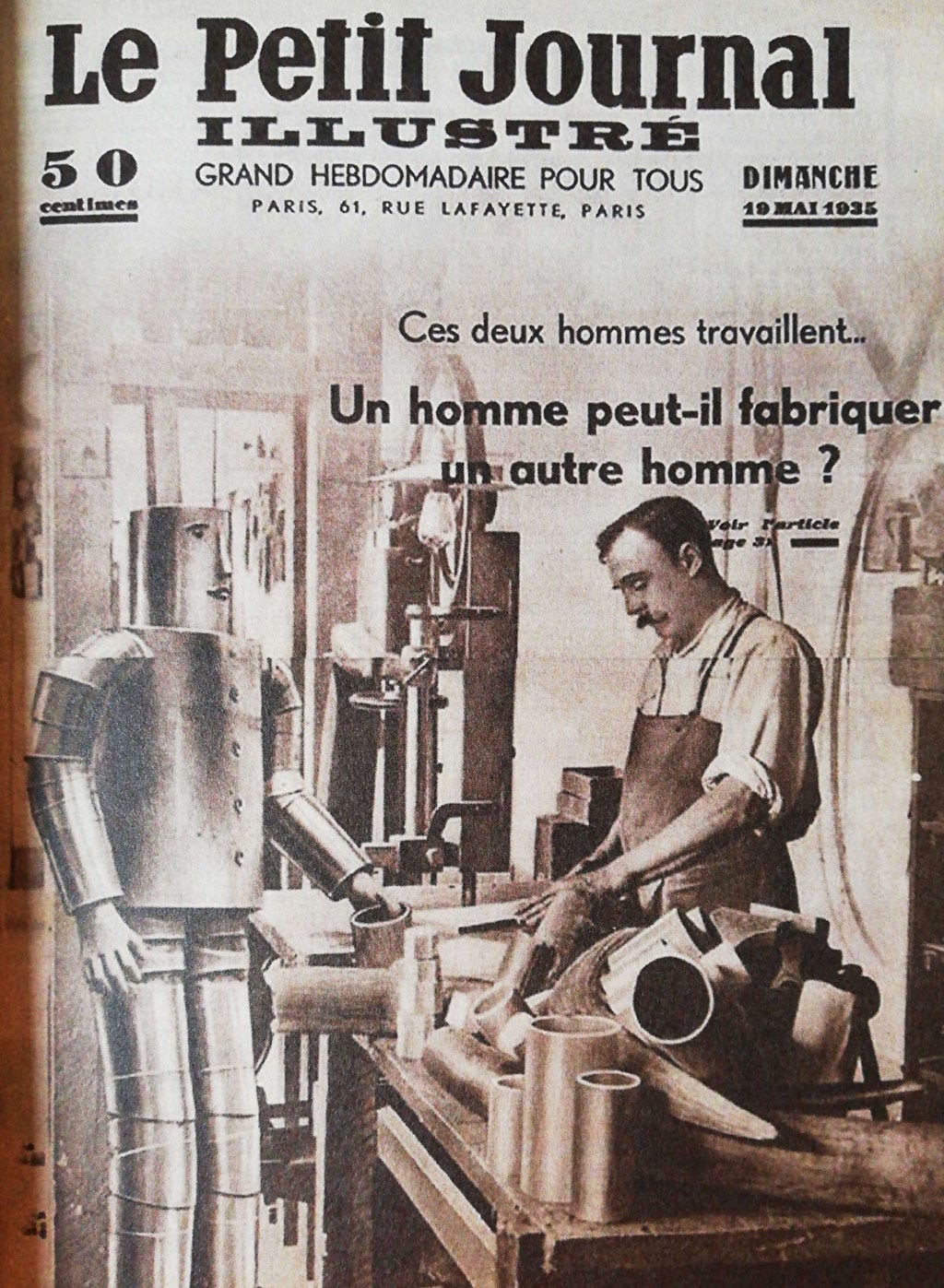

Over the centuries, we have built machines to help us perform tasks that we find difficult or exhausting. Interestingly, the word “robot” comes from the Czech word “robota”, which means “chore”.

The first known drawing of a “humanoid robot” was made by Leonardo da Vinci in 1495 (a mechanical knight). But it was much later, towards the end of the 19th century, that the idea of an automated society, filled with robots at home and work, appeared in literature, science and popular culture.

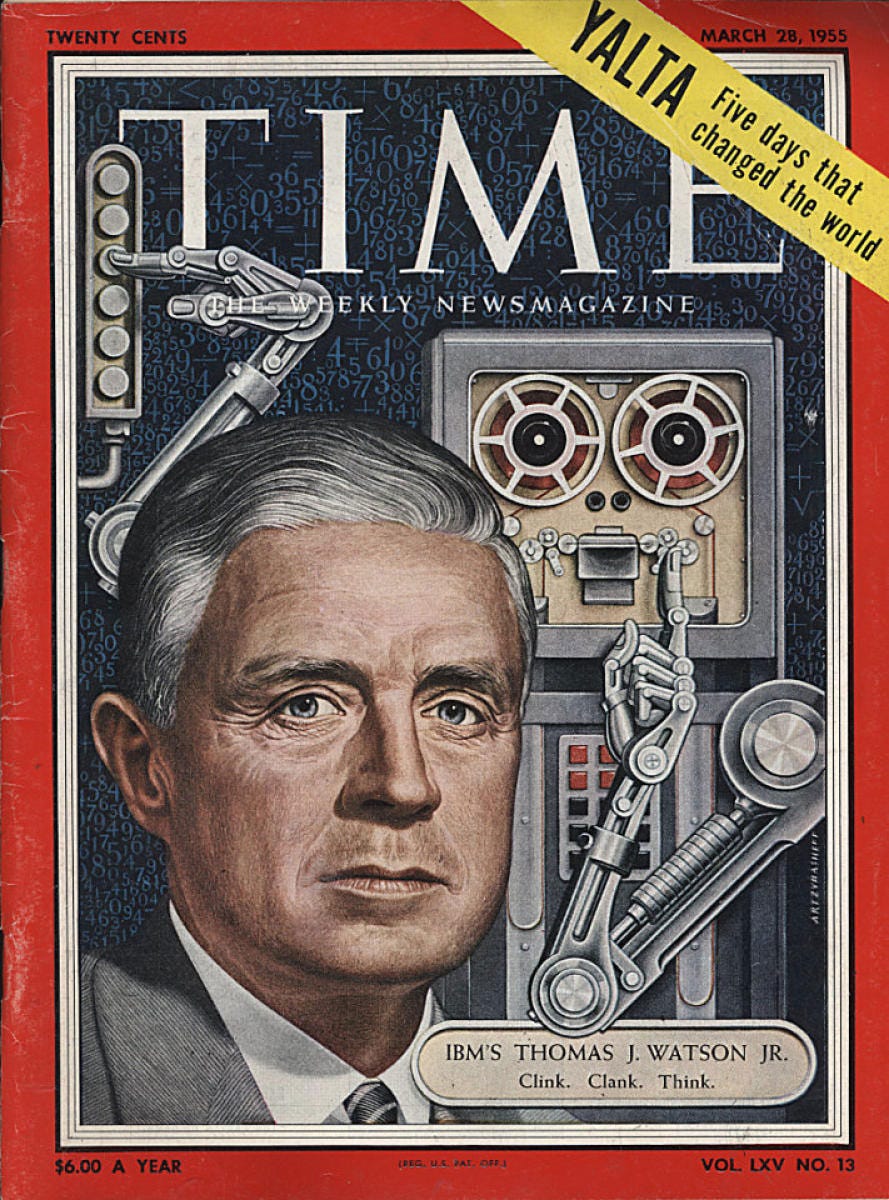

In the early 20th century, the use of cars and traffic lights brought automation to the street level and public interest in robots really took off.

Since then, the number of machines and automatic processes in our lives has grown exponentially.

Our ability to learn, understand, apply our knowledge and improve our skills has played an important role in our evolution and the establishment of human civilisation. And AI is no exception.

But that doesn’t mean that most people see AI as a positive evolution of society.

AI taking over the world is such a recurring theme in pop culture that we may ask if this is how most people perceive this technology. Should we be worried about it? Who will be responsible when a system has unexpected behaviour? Will it change the nature of human beings? What are the risks? Do we need new rules? And why does it matter?

Many people (including Elon Musk) believe that the advancement of technology can create a superintelligence surpassing the brightest human mind and that can threaten human existence.

Nick Bostrom, author of Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies, suggests that new superintelligence could replace humans as the dominant lifeform and defines it as

“an intellect that is much smarter than the best human brains in practically every field, including scientific creativity, general wisdom and social skills”

Damian Rees’ (author for Ipsos UX) vision provides an important nuance, however: AI’s abilities today are probably not as extensive as one might expect.

As AI/ML becomes more context-aware, it will be more able to help us in our daily lives. Rather than trawling through files and folders to find information relevant to a task, the interface will notice the context we are in and offer a small selection of supporting information it determines to be relevant. Our relationship will shift with technology to one where the promise of Siri, or even Clippy in days gone by, can be realised.

📖 Regulation of the use of autonomous weapons is one of the issues being addressed by the European Commission and UNESCO. There is a contemporary example on the South Korean border, where a sentry robot called SGR-A1 uses heat and motion sensors to identify potential targets more than three kilometres away. For now, a human must approve before it fires the machine gun it carries, but this raises the question of who would be responsible if such robots started killing without human intervention.

As a UX designer, I’m always wondering what impact these issues can have on user experience and what working with AI means. To gain a first understanding of the possibilities and assumptions, I chose to dive into the numbers, gathering data from two perspectives: public and professional perceptions of artificial intelligence.

What is possible with AI nowadays?

AI is taking on a new meaning continuously, as we use it more and more in our daily lives. There is no consistent definition, and its understanding varies greatly between the public and experts.

In simple terms, AI allows machines to learn and perform specific tasks without being explicitly programmed to do so — replicating human intelligence with the capacity for reflection and insight. Using algorithms designed to extend what humans can do.

From governments to businesses to schools, the appetite for the growth and development of AI capabilities is growing exponentially. Proponents predict that the financial, political and social gains will be significant. Opponents believe the losses will be even greater.

AI is undoubtedly efficient at performing specific tasks like:

- Algorithms can create processes that handle repetitive tasks and systems are more accurate at performing them

- Efficient algorithms can process large amounts of data in almost no time

- Systems can process increasing amounts of data more efficiently

- Systems can run indefinitely with unlimited computing power

- Algorithms make it easier to make decisions and discover new ideas.

And it may affect nearly all aspects of society, such as the labour market, transportation, health care, education, and national security…

It is interesting to note that these systems are not only involved in repetitive tasks but also involve calculations and analyses. As a result, they compete with highly skilled professionals because they are capable of learning, reasoning, and understanding to meet specific demands.

There are many stories about how AI is improving people’s lives, and just as many illustrate the technology as a job-stealing villain.

📖 To illustrate the potential dangers of AI, Tijmen Schep with his online experience “How Normal Am I?” (for SHERPA, an EU-funded project which analyses how AI and big data analytics impact ethics and human rights) let you discover how recognition systems actually work in practice, in a safe and private environment. Just by looking at your face, the algorithm can make assumptions about your attractiveness, age, gender, and life expectancy.

Many questions can arise about how our data is used, how it is recovered, and how certain individuals are mistakenly identified.

Projects such as SHERPA are essential to helping the EU understand the implications of this growing technology.

To enhance user confidence in AI technologies, UX designers and professionals should be aware of the impact this has: it is essential to distinguish between fact and fiction when speaking about the technology. AI perception is critical because it could shape future research and development, but several studies have found that “human perception” is often not the same as reality.

Our perception does not always align with reality

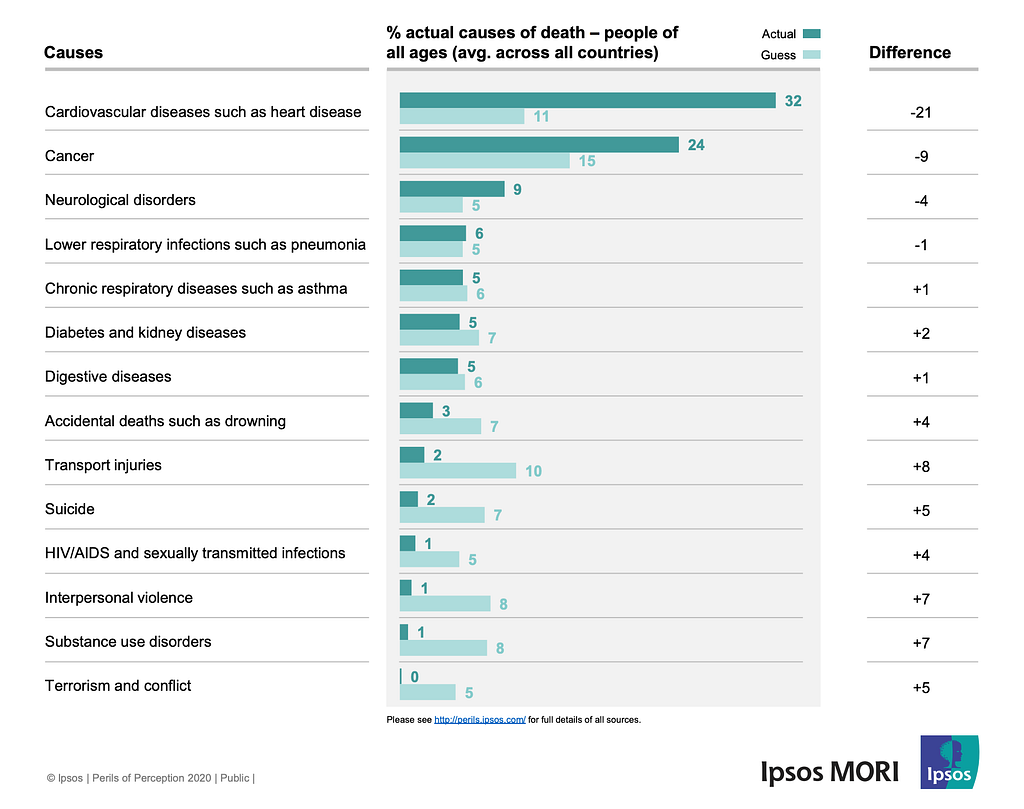

Ipsos demonstrated this point in the Ipsos MORI Perils of “Perception Survey 2020” interviewing 16,000 people and highlighting public misperceptions across 32 countries around the world about the proportion of people who die from diseases, violence, transport injuries and other causes.

Although trends differ between countries, on average, people underestimate the number of deaths caused by cancer and cardiovascular disease and overestimate the number of deaths caused by transport accidents, substance abuse and violence.

There is a range of factors that could influence the guesses, including media coverage and personal experience.

The data shows that at a country level, there are factors which could be having an impact on people’s guesses, but at an individual level it is more complex and the picture is less clear.

This is a fairly concrete example of how these misperceptions can create great friction within societies by having exaggerated visibility. These are prejudices that tend to be exaggerated by social and traditional media, lack of education and even by politicians. They affect the way people perceive the world as a whole and that is why it is interesting to explore what are the perceptions of emerging phenomena and technologies such as AI and what prejudices are related to them.

Public perceptions of AI in numbers

The experience users have when interacting with AI is a key element in determining their perception of it.

As we have seen, AI offers several advanced forms of automation. And in this light, another Ipsos study conducted in the UK in 2018, suggested that the British public “falls somewhere between ignorance and suspicion” when it comes to automation. For example, a majority (53%) would not feel comfortable with AI making decisions that affect them. This suggests that people have limited knowledge of how AI can make decisions.

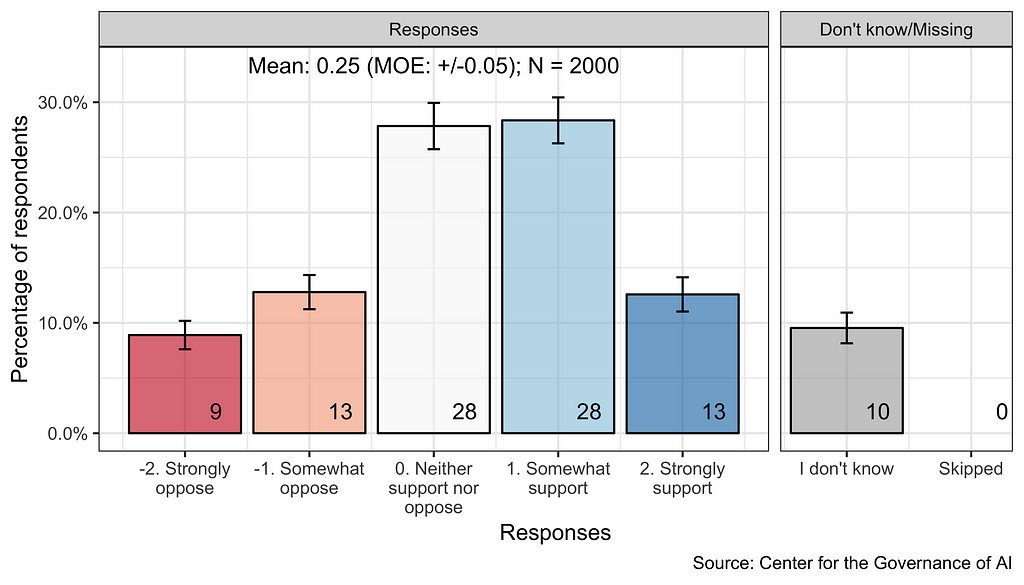

Research conducted in 2019 at The Center for the Governance of AI, housed at the Future of Humanity Institute and University of Oxford, about “Artificial Intelligence: American Attitudes and Trends.” highlighted that more Americans think that high-level artificial intelligence will be harmful than those who think it will be beneficial to humanity.

- 12% of Americans think it will be “extremely bad” and could lead to the extinction of humanity

- 22% of Americans think the technology will be “generally bad”

- 21% of Americans think it will be “generally good”

- 5% of Americans think it will be “extremely good”.

But strangely enough, despite this finding, Americans have demonstrated mixed support for the development of AI.

Furthermore, 77% of Americans expressed that AI would have a “very positive” or “mostly positive” impact on how people work and live in the next 10 years, while 23% thought that AI’s impact would be “very negative” or “mostly negative” (Northeastern University and Gallup 2018)

Most Americans are unable to clarify the nuanced differences between the relationships among AI and other related terms like machine learning, deep learning, natural language processing, and robotics.

A majority think that virtual assistants (63%), smart speakers (55%), driverless cars (56%), social robots (64%), and autonomous drones use AI (54%).

However, they do not believe that Facebook photo tagging, Google search or Netflix recommendations use AI and that it can influence their shopping decisions or behaviour. Most consider AI marketing inevitable and generally acceptable.

Why did so few respondents see the products and services listed to be applications of AI, automation, machine learning, or robotics?

One explanation is that the public lacks awareness of AI or machine learning.

According to a 2017 survey, nearly half of Americans reported that they were unfamiliar with AI (Morning Consult 2017), while only 9% of the British public said they had heard of the term “machine learning” (Ipsos MORI 2018). And similarly, less than half of EU residents reported hearing, reading, or seeing something about AI in the previous year (Eurobarometer 2017).

It is likely that the majority of them are already taking advantage of some of the value-added features of AI in their daily lives, such as voice-over, and are no longer paying attention. The use of AI to personalise experiences and advertising messages intrigues users.

While technologists and policymakers have begun to discuss AI applications, machine learning and regulations more frequently, public opinion (and pop culture) has apparently not significantly influenced these discussions.

What about the perceptions of professionals?

(It seems that pop culture also has an impact in the workplace)

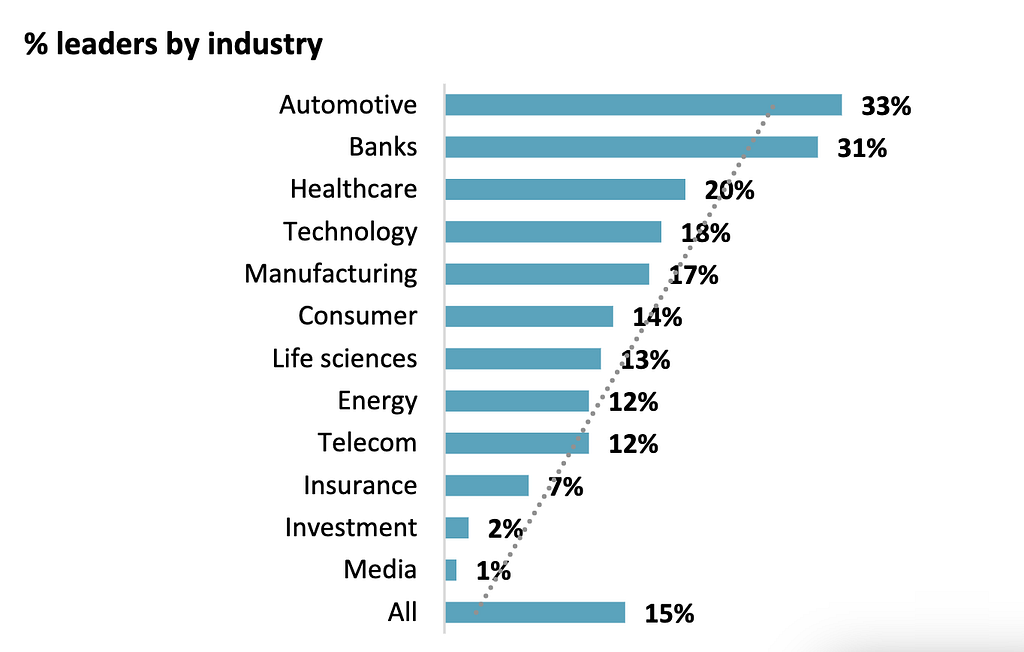

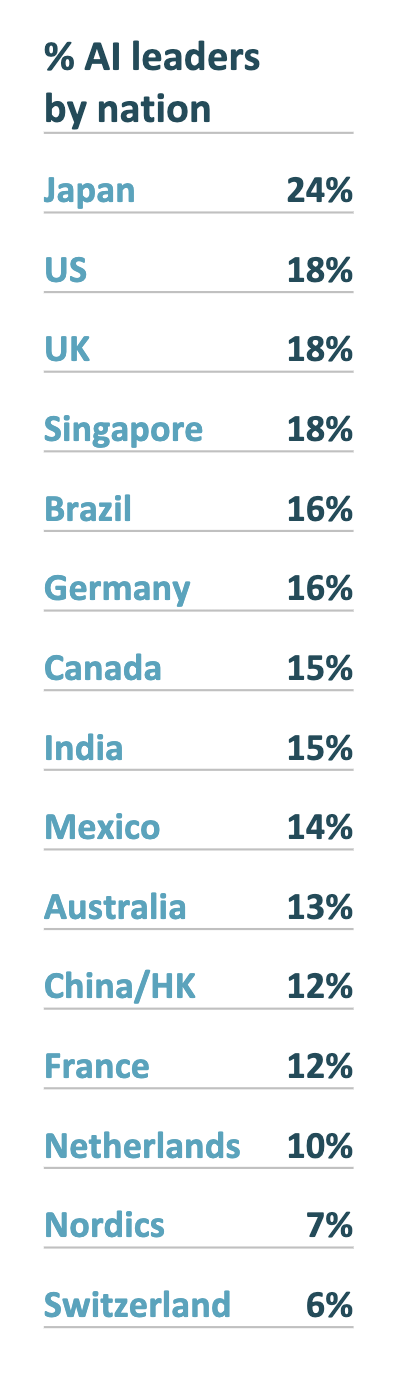

In 2020, ESI ThoughtLab, together with a group of AI leaders, conducted a benchmarking study “Driving ROI through AI” with a sample of senior executives in 1200 companies across 12 industries and 15 countries. Additionally, over 20 in-depth interviews were conducted with AI leaders.

Among the three major sectors most likely to benefit from AI are automotive, finance, and health care.

We can clearly see from the survey that the current level of maturity is insufficient to address all challenges associated with the integration and use of AI technologies:

- 20% are beginners

- 32% are early adopters, starting to pilot AI

- 33% are advanced users

- 15% of companies are widely using AI to generate benefits

In any case, according to this study, the number of firms proficient at using various AI technologies will jump to 63% by 2023.

In the next few years, AI challenges will remain the same but will be added to general concerns about data management. Nine out of ten AI leaders have advanced data management capabilities. And by 2023, 74% of implementers and 35% of beginners plan to implement sophisticated data management systems to enhance AI performance.

Companies face three sets of common AI challenges:

- Project and talent management

- Handling regulatory, ethical, and data security risks

- Data and technology limitations

We could argue that the US leads in the field of artificial intelligence due to advances made by large corporations like IBM, Microsoft, and Google. The ESI ThoughtLab study, however, indicates that when it comes to corporate adoption of artificial intelligence, Japan takes the top spot (that could be used as another example of a perception dilemma).

An explanation could be found in the following three points:

- As part of its Society 5.0 program, the • Japanese government is partnering with the private sector and investing billions in AI.

- Companies and workers in Japan view AI more favourably, seeing it as an enhancement of jobs, not a replacement.

- Compared with other economies, Japanese companies invest more in AI and have larger AI teams.

According to another survey, “AI on the Horizon”, conducted in 2019 by Headspring and YouGov, AI remains unknown to most due to pop culture.

50% of professionals know a fair amount to a lot about AI and 48% say they have moderate to poor understanding. Only 2% have never heard of AI before.

More than 50% of office workers would trust a decision made by a human more than a decision made by artificial intelligence. Less than 20% of professionals would trust an AI decision over a person’s.

Two interesting and major findings emerged as priorities in this study: the need (and desire) to invest more in people and training; and the implementation of processes to manage ethics around AI.

- The willingness to learn and engage seems high: 43% of the professionals already use AI or feel prepared to use it within the next year. Even if the confidence in their company’s AI-readiness is far lower and 2/3 think their employer is not prepared.

- AI is no better than humans at fostering diversity: more professional office workers disagree with the suggestion that AI will help create a more diverse workforce. 40% believe it will contribute to greater diversity, but one in six don’t know.

Investing in people and technology

Communicating about AI topics comprehensively and constructively, recognising the risks while avoiding the hype (due to pop culture again) can help workers and citizens start preparing for an AI future today.

Workers need to feel confident to engage and better understand AI.

📖 Initiatives like AI4ALL, a non-profit organisation that focuses on developing a diverse and inclusive pipeline of AI talent in underrepresented communities through education and mentorship, are good examples of creating fertile ground for engagement and broader collaboration.

AI is no better than humans at fostering diversity

In the study conducted in 2021 by Momentive, about knowledge workers’ perception of AI (in which they surveyed 533 knowledge workers in the US) the tensions between the importance of AI in business systems and the perceived association of the technology with bias are clearly identified.

AI can assist in identifying and reducing the impact of human bias, but it can also exacerbate the problem by incorporating and deploying bias at scale.

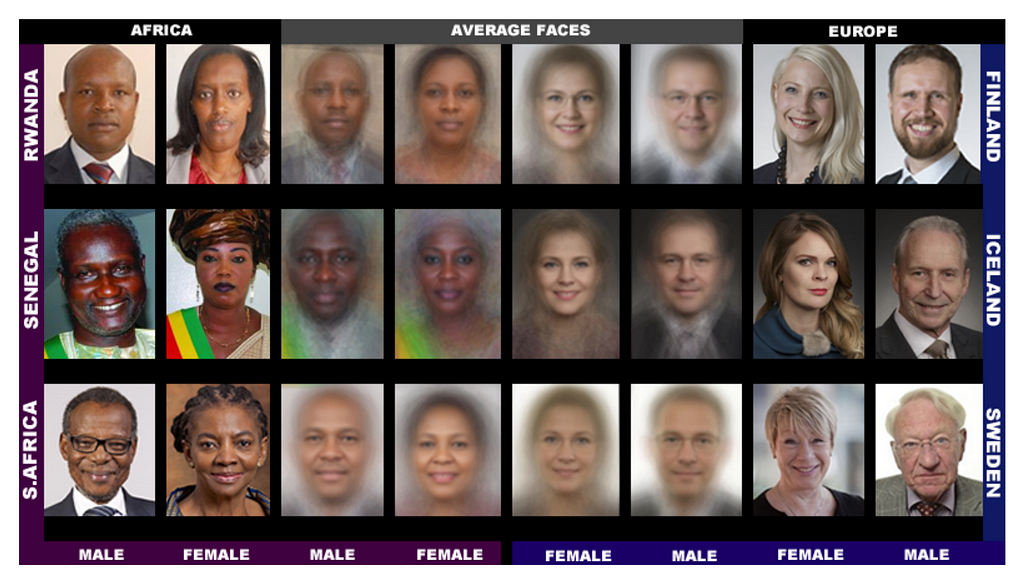

When algorithms are trained on biased data this can lead to poor predictions, inaccurate or outdated results, discrimination and even the enhancement of harmful content, and racist and sexist systems.

Biased data is clearly identified as one of the limitations of AI (like the limited quantity of data, poor quality of data, etc…) and according to Jing Huang, director of machine learning engineering at Momentive, this is not an isolated problem.

The machine we teach can only be as good as its teacher. If there is no diverse representation among the data scientists and engineers who build the algorithm and teach the machine to learn, you won’t have a generation of artificial intelligence that is representative of our human society.

It is not for nothing that popular depictions of robots destroying the world are mad robots created by mad scientists, who dream of dominance and revenge. More rarely, the scientist is just naive and completely overwhelmed by his creation (like Frankenstein). But what’s important to remember is that robots themselves are not evil without their evil creators.

With the adoption of AI, the issue of minimising bias is rising to the forefront. These issues are amplifications of issues that already exist, including discrimination.

In the field of artificial intelligence, many systems are known to be biased since they are based solely on historical information. The face recognition algorithm has proven to be the least accurate of the five most commonly used biometrics (fingerprint, iris, palm, voice, and face), and when tested on black women, it is even worse.

Even though face recognition algorithms have been improving over time, racial bias needs to be addressed, and its applications need to be improved to become more equitable and effective. In terms of artificial intelligence and machine learning in general, identifying and eliminating inequalities has become even more important.

To prevent prejudices and biases from developing, we should promote diversity.

Promoting diversity

48% of workers (Momentive study, 2021) believe that AI algorithms are not written by teams of engineers with sufficiently diverse backgrounds.

In the report of 2018 The Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence: Forecasting, Prevention, and Mitigation the authors recommend that “policymakers should collaborate closely with technical researchers to investigate, prevent, and mitigate potential malicious uses of AI,” and we should “actively seek to expand the range of stakeholders and domain experts involved in discussions of these challenges.”

Including more diversity in development teams can improve the quality of public information and avoid hysteria and misinformation about AI.

Homogeneous AI teams are seen by many industry leaders as the technology’s main obstacle and the roots of bias.

61% of knowledge workers said that the data that feeds AI is biased (Momentive survey). The fact that so many people recognise bias in AI systems is consistent with a wider, industry concern and working to reduce the bias is an urgent priority.

Bias can affect everyone by reducing our ability to contribute to society. Bias reduces the potential of AI for business by increasing professionals’ mistrust of their dataset and producing biased results.

Business leaders and organizations need to ensure that AI systems enhance human decision-making. To build more equitable data science applications, they need to be aware of the historical and social context in which they build pipelines, and they must implement standards that will reduce bias.

📖 Amazon stopped using a hiring algorithm after finding it favoured applicants based on words like “executed” or “captured” that were more commonly found on men’s resumes, for example.

But this does not stop the majority of knowledge workers from thinking that their future lies with AI. Also in the Momentive study:

- 73% believe that AI is fully capable of making unbiased decisions on behalf of humans.

- 39% believe AI helps humans become more effective overall, and 40% believe it helps spot trends that human data analysts could overlook.

- 86% of people said that AI is “important” or “very important” when their organization is selecting enterprise technology to purchase

- The use of AI-driven software spans departments, with the highest use falling to IT (54%), marketing and sales (44%), and finance, procurement, and accounting (41%).

The emergence of new technologies requires new rules

It appears that the main problem is that the algorithms engineer (the human) who makes developments on their own individual and fallible perceptions could lead to abuses if laws and regulations are not put in place.

It is up to us to build a future where humanity and artificial intelligence coexist for the common good.

From an overall perspective, from professionals or/and the public.

In the end, AI probably won’t burn down your house, but it will surely change societies, mentalities, and the work we do today.

How can we best anticipate a world where work is radically transformed if not by putting in place relevant regulations and by offering the possibility to make people evolve (education, information, communication):

- Instilling ethics in AI systems

- Adapting our societies to a world in which automation will make many of our current manual jobs redundant

- Creating state regulations to prevent AI from being built for a sole purpose and creating national commissions to monitor companies

- Developing education and mentoring initiatives to represent all communities

- Creating initiatives to support and educate people about career changes

Conclusion

The problems that emerge from AI are an amplification of already existing problems (discrimination, social injustice…). And these are the issues we need to address. More diverse development teams would be better positioned to detect and anticipate bias.

Most AI systems today are based on learning from historical data. There is the fact that humans are themselves very biased in the way they make decisions. And if systems learn from this past data and human decisions, they inevitably incorporate these biases. In this sense, the use of AI technology to amplify or compensate for discrimination always depends on “humans”.

Citizens should not need to understand the technical processes behind AI to use it fully. It is the data professionals, engineers and scientists, as well as the marketing departments and governments that are responsible for regulating these technologies, who need to understand the social and ethical dimensions of artificial intelligence.

The next big step, as we have seen with the European Commission and UNESCO, is the implementation of the capacity for common sense through regulation. Artificial intelligence is evolving very quickly and dynamically, and machines will inevitably be asked to make more decisions. Regulation is essential to respect a universally beneficial approach.

The best strategy at the moment is to put regulations in place but also not to fear the progress that can be made through AI. Having said that, I seem to be on the optimistic side. I see AI being able to take huge amounts of information and make sense of it in a way that humans simply cannot.

The development of AI is creating new opportunities to solve wicked problems Climate change, Poverty, Disease, War and Terrorism, Animal abuse, Racism, Population Growth and much more…)

For IBM’s head of research, Guru Banavar, “AI will work with humans to solve pressing problems such as disease and poverty”.

And I don’t want to see the possible “dark side” (technology that can cause harm, technology that can create weapons, information gathering technology that violates laws, safety or privacy…) — AIs that will turn on us to kill or enslave us.

To some extent, yes, we should fear AI.

Today, Ai based systems have no consciousness, no independent thought and certainly cannot question what they do and why they do it.

The fear of what AI might be used for, or the impact it might have on our societies, who uses it and how should drive us to find innovative ways to make the best of it without having to face the worst.

“The future cannot be predicted, but futures can be invented. It was man’s ability to invent which has made human society what it is.” Quote of Dennis Gabor, a physicist who won the 1971 Nobel Prize for inventing holography, in his book “Inventing the Future” in 1963

Thank you for the time you spent reading this article!

I want to share what I am learning throughout my UX research that I feel can be useful. I hope you have found this article informative and I hope it has given you insights into your own work.

I will continue to share what I learn in my research and look forward to your feedback.

To have more information about the draft of the European Commission and the UNESCO draft:

- “Proposal for a Regulation laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence” by the European Commission, 2021

- “Draft Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence” by UNESCO, 2021

Some references and interesting links:

- “Why we should not fear Artificial Intelligence” by Lorena Jaume-Palasí, 2018

- “Should We Fear Or Embrace Artificial Intelligence (AI)?” by ed-watch.org, 2021

- “16 Examples of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Your Everyday Life” by The Manifest, 2018

- “Les robots comme vous ne les verrez plus jamais” French book of Hugo et Compagnie, 2015

- “Consumers’ perception on artificial intelligence applications in marketing communication” Qualitative Market Research, 2021

- “AI on the Horizon: Headspring Launches Research on the Impact of Artificial Intelligence in the Workplace” by Thiago Kiwi, 2019

About bias and discrimination:

- “What Do We Do About the Biases in AI?” by James Manyika, Jake Silberg, and Brittany Presten, 2019

- “The Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence: Forecasting, Prevention, and Mitigation” 2018

- “Racial Discrimination in Face Recognition Technology” By Alex Najibi, 2020

- “Gender Shades: Intersectional Accuracy Disparities in Commercial Gender Classification” report of Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru, 2018.

- “The perpetual line-up — Unregulated police face recognition in America” report by Clare Garvie, Alvaro Bedoya and Jonathan Frankle, 2016

- “Advancing racial literacy in tech — why ethics, diversity in hiring & implicit bias trainings aren’t enough” a project was conceived and launched under Data & Society’s Fellowship Program, by Jessie Daniels, Mutale Nkonde and Darakhshan Mir, 2019

Is AI going to steal your job and burn down your house? was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.