The power of visual symbols in building credibility — whether for good or bad.

Written by Fabricio Teixeira and Caio Braga

From the moment we as humans started to organize ourselves into larger groups, following social contracts to ensure a certain level of order became crucial. As historian and philosopher Yuval Harari explains, it’s easy for us to acknowledge that primitive tribes cement their social order by believing in ghosts and spirits and gathering each full moon to dance together around the campfire, but it’s harder for us to appreciate that our modern institutions function on exactly the same basis: fictions. Whether it’s money, ethics, laws, countries, religions, flags, totems, fashion, music, arts — most of us accept, believe, or at least abide by multiple social contracts at any given time. Because they are so powerful and omnipresent, we often don’t acknowledge that they are not laws of nature, but fictional constructs.

Power both creates and depends upon these shared fictions. To control these fictions, they must be coded as legitimate and immediately recognizable through their symbolism, language, and design. Think about money (in paper form) as an example. When you look at a U.S. one-dollar bill, you know exactly what it is and where it is accepted, and you have a rough idea of its value.

The design of the dollar bill is full of meaning. Each symbol builds on top of older symbols and, by design, many of them are familiar to the people who use it, who are bound by the social contract of U.S. currency.

Many of these visual symbols of trust draw on centuries of design evolution. Coins, seals, certificates, and other official documents from various regimes and cultures have contributed to a collective visual lexicon of symbols that convey legitimacy and trustworthiness.

To this day, when someone wants to reference the dollar bill in a design, it’s noticeable how certain visual cues remain — even when the medium and the level of fidelity are completely different. Leveraging mental models from previously established fictions helps create a feeling of familiarity, which in turn helps people believe in the new, emerging fiction.

As designers, when we are creating digital products that will be used by our audience, we are too borrowing visual symbols from other parts of culture and leveraging them to imbue meaning across the experience. With the right combination of symbols, we are able to make brands look more credible, users feel more comfortable, products feel more secure — and quite significantly transform the way people experience the digital interface we are creating.

Think about the classic lock, shield, and checkmark icons you see when you check out on an ecommerce website. Those are meant to represent security and give users the feeling that they do not have to worry about how safe their data is — although the design of the icons themselves has no connection whatsoever with the technology that powers the transaction happening behind the scenes.

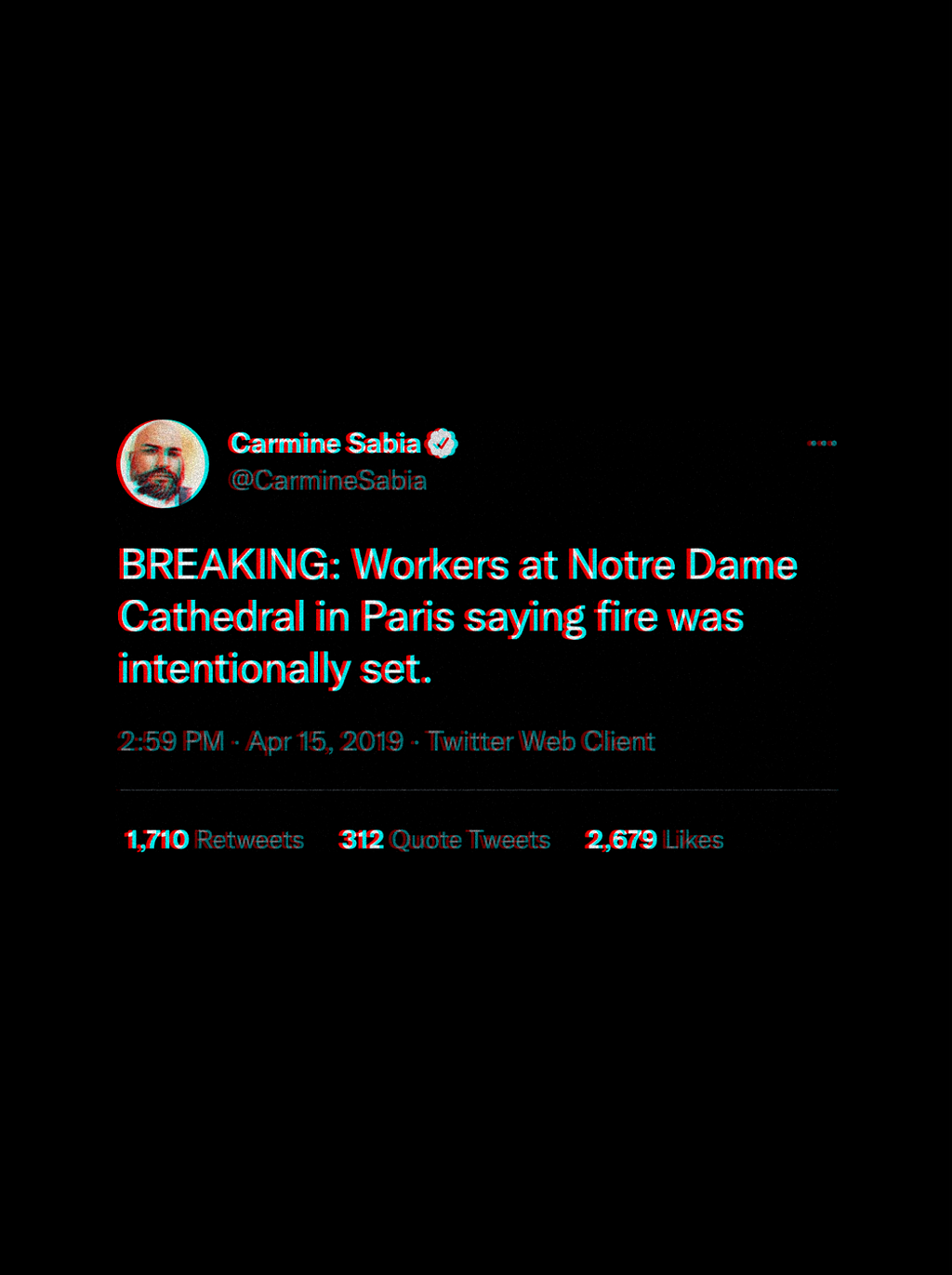

Design for trust can too be misleading. With design tools being accessible more widely, anyone can now create symbols that look and feel as credible as century-old institutions.

Think about the logo for science-denier group Flat Earth Society, or even Twitter’s Verified Badge: are those icons of trust? Many Twitter accounts that spread misinformation are verified, causing additional confusion on what is true — and who holds the truth.

The process of questioning, antagonizing, and creating new fictions is natural, but the scale, speed, and intensity of social media radically changed how quickly this process takes place. The “Viking at the Capitol” image, for example, widely imitated across social media in recent years, mixes the American flag with nordic symbols to create a facade of trust, to then invade the building that is supposed to be the holding ground of modern democracy.

When fictions (new and old) get mixed together, new narratives are created at the speed of culture. As designers, we have the power to modify and repurpose old symbols, as well as the responsibility of doing so.

Are we still replicating eurocentric models from 5 decades ago to define our future? Are we questioning the value old constructs bring to our day and age? When we free ourselves from old symbols — what are other futures we can create?

For more articles like this:

Can trust be designed? was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.